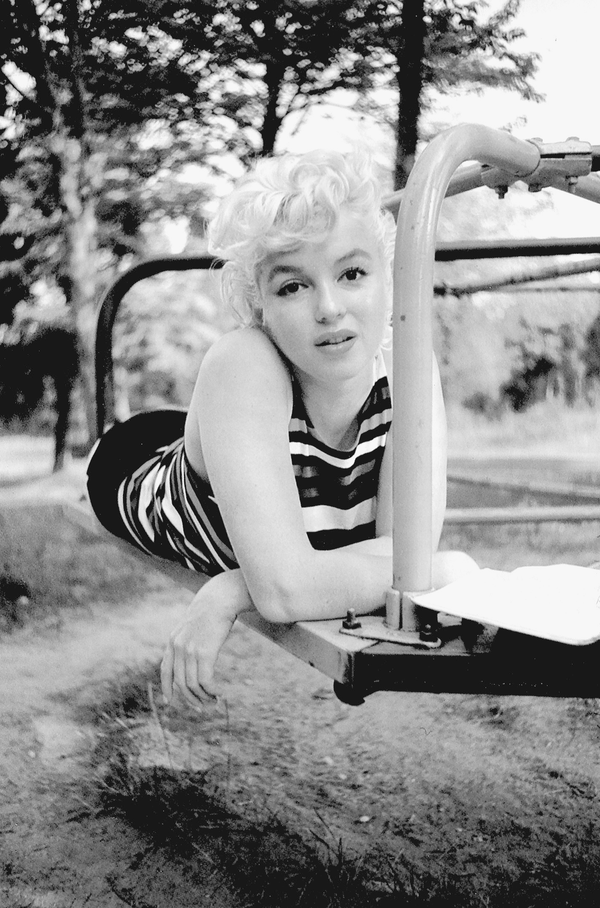

Marilyn Monroe, Humphrey Bogart, and Laurence Olivier are three of the biggest names in the history of Hollywood, and they all have one thing in common: they emerged from Hollywood’s Golden Age. Between the 1910s and 1960s, Hollywood experienced an influx of experimental filmmaking – these were revolutionary years, filled with exceptional talent, new camera technology, and more freedom for scriptwriters. While the years of a thriving Hollywood industry seemed they would last forever, they did inevitably come to an end. This is the rise and fall of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Film In Its Earliest Years

Before the big screen was invented, theatrical entertainment was confined to a stage. In the late 1800s, early filmmakers wanted to shift this method of storytelling in favor of projected images on a screen. However, the first films were still forced to the confines of a small stage and shot at an unmoving wide angle. Cutting to different scenes was so limited that when it did occur, it was

By the 1910s, filmmakers learned how to alter space and time on screen. Or really, they used varying angles and created multiple sets to portray spatial and temporal movement in ways that real-time stage acting could not. This was a breakthrough in modern storytelling. Filmmakers like David W. Griffith built independent film companies and began experimenting with such techniques, creating some of the earliest masterpieces in film. In 1913 alone, The Mothering Heart, Ingeborg Holm, and L’enfant de Paris reached new heights in cinematic storytelling.

In 1915, Griffith released The Birth of a Nation. Filled with monumental filmmaking breakthroughs, it became a staple of the film

A New Age Of Cinema

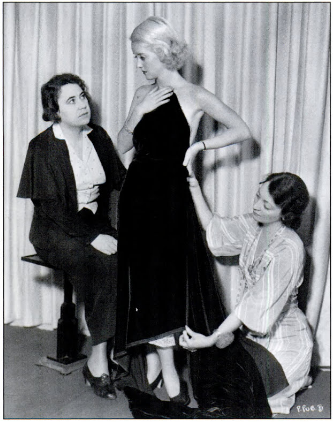

In 1920, the filmmaking landscape was again revolutionized when sound was introduced. The production of sound changed with the introduction of the studio system. These were the earliest large motion picture studios, complete with their own resources to create feature films. By the 1920s, actors, actresses, and filmmakers who had worked on independent projects throughout the earliest years of film joined up with one of these studios to begin their careers as on-screen performers.

Though there is some discrepancy when the sound era officially began, the 1927 release of The Jazz Singer signified a radical shift in the film industry. For the first time,

MGM Films, Twentieth Century Fox, and Paramount were the leading companies producing most of the decade’s major films. However, with the conjoining of sound and pictures, many film critics argue the artistic quality of the films during this era suffered. It took until the late 1930s for cinema to gain a foothold in modern technology, and start producing films with the same creative aesthetics as they did while still silent. But once they did, film cemented itself as a foundational form of storytelling.

Developments In Film

In the year 1939, filmmaking again peaked with the releases of Wuthering Heights, Gone with the Wind, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The Wizard of Oz, and more. All films released during these years were defined by advancements in three levels: film devices, plot, and technology.

First, film devices like continuity editing were utilized by filmmakers to slice up scenes, giving viewers varying perspectives of time and space. Likewise, the 180-degree rule had filmmakers pretend there was a line running along the 180-degree axis of each shot, informing where the camera should be placed to be aimed at the center of action. The cross-cut, which revealed simultaneous action in different locations, and axial cut, which contained no cutting but

Related: The Father of Film: Thomas Edison

Second, a sense of plot. The general narrative logic was driven by relatable human characters and established by a clearly marked beginning, middle, and end. In this form, the narrative is structured by a standard cause and effect formula. Cinematic time was also created. This functions similarly as a narrative logic but also included flashbacks throughout the story.

Lastly, other technological improvements included artificial lighting, low-key lighting, and fire effects. All of these played with shadows and light to create anything from a light-hearted to sinister mood in a scene. As a result of these advancements, films got longer, and plotlines more complex. Stories that were once confined to paper as books or plays were transformed visually to be consumed by wider audiences. All of this combined established a booming industry that lasted through the middle of the century.

The Golden Age Comes To An End

Hollywood’s Golden Age finally came to an end due to two main factors: antitrust actions, and the invention of television. For decades, it was common practice for major film companies to purchase movie theaters, which would only show their company’s produced films. This type of monopoly forced Assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold to take up a case against the eight major Hollywood corporations at the time. He claimed they were in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act which regulates competition among large corporations.

As a result of the court case, every Hollywood corporation signed a consent decree agreeing to release their hold on spaces that showed only their films in theaters nationwide, to stop the pre-sale of films in various theater districts, to prohibit film companies from scheduling more than 5 films in theaters, and finally, to establish a board to enforce these rules.

As these rules began to take effect, Hollywood started revising and releasing the contracts of their employees, thereby completely rewiring the infrastructure of the industry. The traits that made each company individual vanished with the overhaul of their creative teams. The shift ultimately led to fewer movies released, but larger budgets for each individual film.

In addition, the increasing presence of televisions in the homes of average Americans, and the growing popularity of television shows presented traditional movie theaters with steep competition. This, combined with the new antitrust regulations, meant there was less money fueling the industry thus creating a decline in filmmaking and profits.

Hollywood’s Golden Age were pivotal years in the history of filmmaking. They established much of the technology that was built upon to create today’s films. While it may not have lasted more than a few decades, it had an indelible impact on the industry as a whole. A short, but crucial part of the development of film, the Golden Age of Hollywood are years that are revered in filmmaking history.