By the turn of the twentieth century, train travel was commonplace and relatively safe, even on far-flung routes through the harsh mountain landscape of the Pacific Northwest. But in the winter of 1910, Washington state’s Cascade mountain range was hit with an especially long blizzard, creating multiple disasters on snow-covered train tracks near the small village of Wellington. Ninety-six travelers, railroad workers, and rescuers would perish in what would be know as the 1910 Wellington Disaster.

Wellington

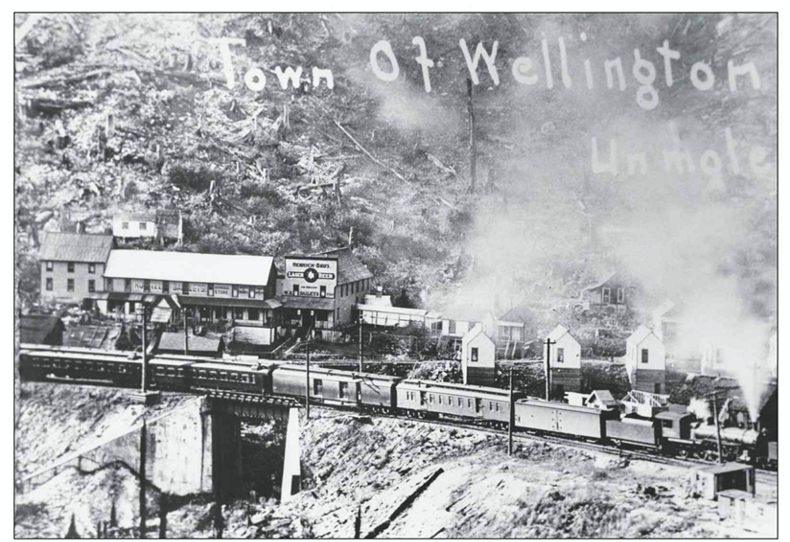

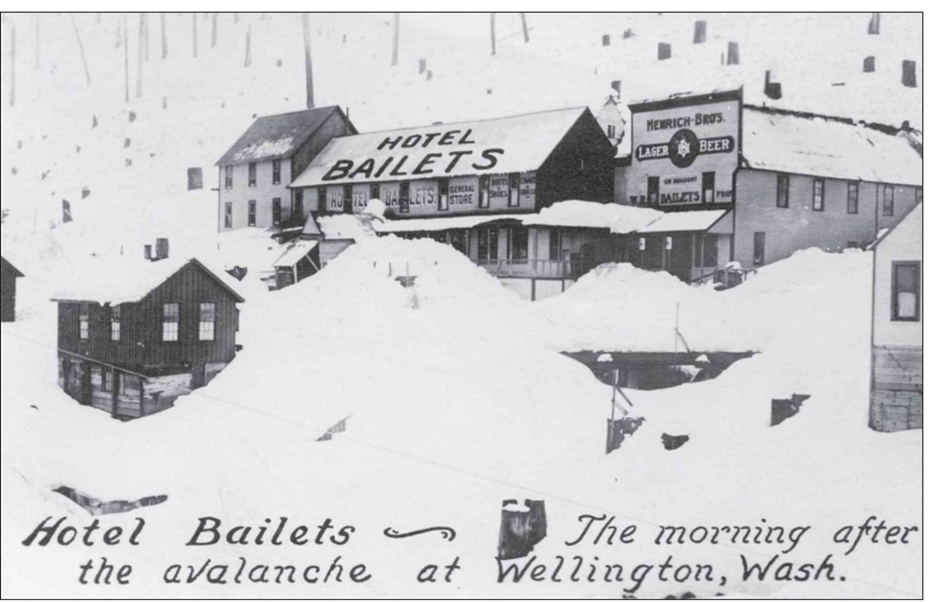

On February 23, the remote wilderness was hit with five or more feet of snow, and days later, snow gauges measured 17 feet. Small towns like Wellington in the Cascade mountains relied on trains for their logging industry, and small Wellington had a power plant, small hospital, hotel and saloon, post office, grocery store, a few shacks, and a train depot. Aside from rail traffic, only telegraph lines connected them to the rest of the world.

“Cascade Cement”

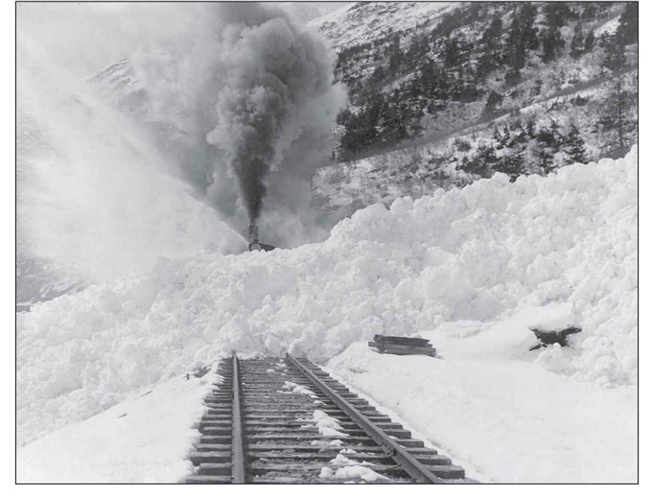

Late February saw relentless snow, making it difficult to keep the train tracks clear. More would slide down the slopes, burying the tracks deep under the dreaded “Cascade Cement.” Great Northern Railway crews worked nonstop to free the tracks. Powerful mechanical rotaries removed snow, but couldn’t chew up trees and debris included in the icy mix. In an unprecedented move, the rail owner shut down the Cascade Division. With telegraph lines down and rotaries choked, rail travel submitted to the weather emergency.

Nine-Day Blizzard

On March 1, 1910, following a nine-day blizzard, rain, thunder, and lightning besieged two trains that had been stopped. While the Seattle Express No. 25 and the fast mail No. 27 trains were stuck waiting to reach Seattle, the entire town gave shelter to the 100-plus extra people stranded there. Many more remained on the train. Ironically, passenger safety was the reason the railroad crew kept the train from hunkering down inside an adjacent tunnel, where noxious fumes and gases threatened. Suffocation seemed worse.

Related: The Fire that Nearly Destroyed Fort Wayne’s Wolf and Dessauer

“I do not see how it could be possible for a man to do any more; a man can work all the time and do all that is in his power, and I could not see anything possible for them to do more than what was done.” — H.L. Wertz, a stranded train passenger

84 W V M , 87-142-10.) Image sourced from The 1910 Wellington Disaster.

Avalanche

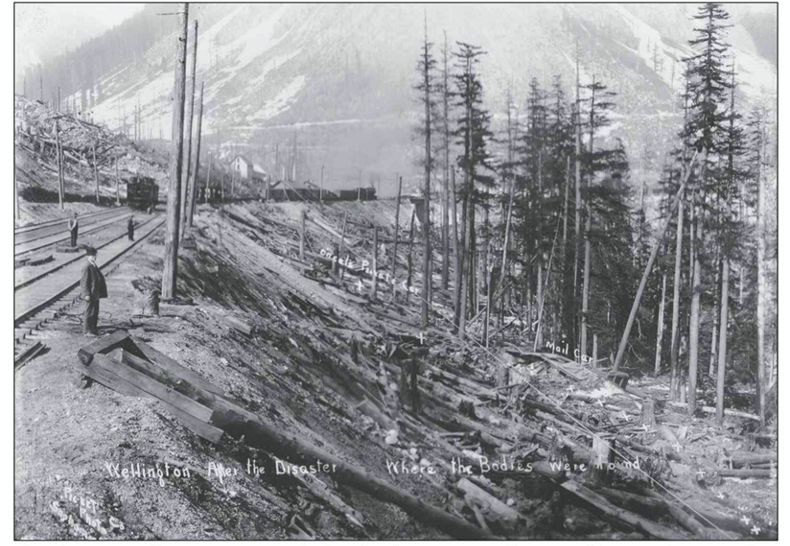

The avalanche was unstoppable. The passengers who remained on the stranded train were ultimately crushed by the enormous avalanche a half-mile long, a quarter mile wide, and 14 feet thick—approximately 10 acres of snow—killing them within seconds. Only one clerk in the fast mail train survived. The night of the avalanche, 19-year-old Alfred Hensel fatefully slept in the other end of the cay, away from his coworkers. The avalanche broke the fast mail car in half, killing the other eight on board.

Heroes

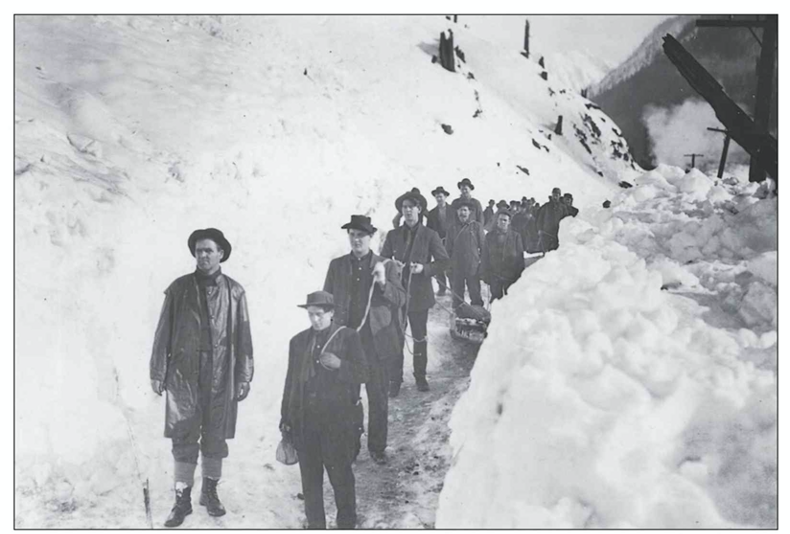

One rescue rotary went missing three miles west of Wellington — the entire crew of 20 was lost under a landslide. Recovery crews dragged the bodies on sleds for miles until they could be hoisted down a slope to nearby Scenic. The gruesome task included tying a rope to the victims’ feet, then lowering the bodies head first, before reaching the recovery train.

Legacy

Great Northern invested millions to build a snowshed at the disaster site, hoping to spare lives in potential avalanches. Wellington was renamed Tye by the Great Northern in the hopes of removing any bad associations from the area, but it wasn’t enough to save the community. The New Cascade Tunnel opened in 1929, bypassing Wellington altogether. Today, all that remains is a crumbling snowshed lined with hundreds of rotten railroad ties and the old Cascade Tunnel at the site of America’s deadliest avalanche.

Want to read more? Check out The 1910 Wellington Disaster and other similar disaster titles at arcadiapublishing.com!