For the past century, the legend of Diana of the Dunes has grown as wild as the environs in which she lived. Diana, whose legal name was Alice Mabel Gray, became famous in 1915, when she stepped onto an old path in the dunes and followed it to the edge of Lake Michigan.

Today, of course, this area is part of the Indiana Dunes National Park and is dotted with many nearby towns. Before 1900, however, most people considered the dunes largely uninhabitable; the press often referred to it as “trackless wasteland,” unexplored and loosely claimed. The steel industry had started to move into the area, but it was still not as welcoming as today.

That’s why Alice chose to escape there. She found permanent shelter in an abandoned shack near a sandy ridge, turning her back on Chicago and all the incumbent responsibilities of living and working in the city. Alice, intelligent and free-spirited, had responded drastically to society’s rigid conventions: she excused herself completely from its rules and routine.

At age thirty-four, this Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Chicago traded her single, working woman’s life for a rougher, yet more thoughtful, existence in the untamed dunes of Indiana, some forty-five miles southeast of the city. From the doorway of the shack she claimed as her own, Alice fearlessly guarded her privacy and her right to live in the sand hills—alone.

Her audacity bewitched and befuddled enough eager reporters that Alice quickly became an enigma, a prime target for front-page news in an era of sensational headlines; she grew legendary in her own time. When they weren’t calling her a goddess, reporters treated her like a sideshow performer, a mystifying and curious misfit.

Although given other nicknames by reporters and townspeople—for example, Nymph O’ the Dunes—Diana of the Dunes instantly took hold when it was suggested by a Chicago newspaper in the days just after her discovery. A November 1916 headline blared, “‘Nymph’ Alice Now a ‘Diana’”; below it, in the article’s second paragraph, she was compared to mythological Diana, the Roman huntress. The writer noted that she was a better shot with her rifle than most local men—especially when it came to duck hunting:

“This strange woman is recognized here as a veritable Diana. Nimrods who returned with one lone duck as a result of a hunt in the dune observed with envy a score on the line at Miss Alice’s windowless cabin.”

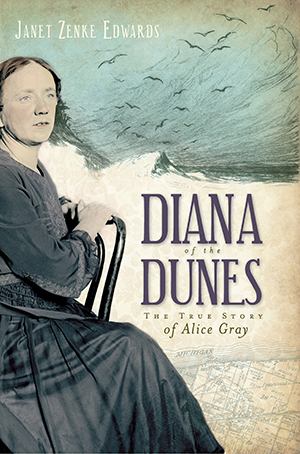

Read diary excerpts from Alice’s own voice in Diana of the Dunes by Janet Zenke Edwards >

In an early interview, granted nine months after Alice’s arrival in the sand hills, a Chicago reporter quoted Alice as saying that the life of a wage earner in the city was akin to “slavery.” To escape the inequality and incivility of the work world and probably, too, to escape a difficult love relationship in the city, she sought a solitary life in the Indiana dunes—her inspiration derived from a poem by Lord Byron titled “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,” in which he wrote the line, “In solitude, where we are least alone.”

During her years in the Indiana dunes—the final ten years of her life—neighbors and reporters alike took copious and creative notes, assigning traits and activities to Alice, both true and false, which are still reflected in prevailing stories. The most popular is that she bathed naked in Lake Michigan (as soon as the ice began breaking up, so some of her contemporaries reported, although Alice denied this) and did so often, running a length of beach to dry her body.

Other familiar details:

Alice, with weathered skin and a rather indistinct frame, seriously studied dunes flora, read voraciously and wrote manuscripts that she kept private; some of her writings were later stolen, others lost to time—a partial diary survives and is appended. She fished and bought salt, bread and other staples in town. Suspected of stealing food and blankets when times were hard, people also said she borrowed sturdier shelter from vacationers who owned property in the dunes while those owners were away. She walked endlessly, dressed simply in makeshift skirts or khaki pants, talked softly and boldly quoted poetry to intruding reporters.

Seeded by those early reporters, Alice’s tale rooted quickly and deeply in regional history, blossoming as legends do. Even today, her story continues to sprout wild, hybrid shoots of both truth and rumor. The names of local businesses, a town festival, a street, vacation homes—even the naming of a sand dune—have paid homage to Diana of the Dunes. Ghost stories, each with invented details and all claiming reports of Diana “sightings,” are published in print and online. Local librarians are quick to point out that Diana of the Dunes is a favorite research subject at the reference desk.

Each of these details speaks to the truth and timelessness of Alice Mabel Gray’s remarkable story.

Finish Alice’s story in Janet Zenke Edwards’ Diana of the Dunes:

“This book was a wonderful read. True story with lots of intrigue and historical details.” – Reader Review