On June 10, 1652, at only 28 years old, Massachusetts silversmith John Hull opened the first mint in America in defiance of English colonial law. The first coin issued was the Pine Tree Shilling, designed by Hull.

This mint produced coins from 1652 to 1682. As compensation, Hull was allowed to keep 6 percent of all the silver he minted, which was a substantial percentage.

In recognition of this day in history, we’ve compiled a few related books you might find interesting.

The United States Mint in Philadelphia by Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez

Following calls by Alexander Hamilton and other Founding Fathers for the nation to issue its own money, Congress passed legislation to officially establish the United States Mint in 1792. Growing from its humble beginnings as a collection of small buildings in the nation’s onetime capital city of Philadelphia, the United States Mint now stands along Independence National Historical Park as the largest coin factory in the world. While the Philadelphia Mint is one of several official United States coin manufacturing facilities, it remains the heart of coining operations in the nation and is also one of the most popular attractions in “The City of Brotherly Love.” You can find this book here!

Related: Philadelphia Soul – Spiritual Values in the City of Brotherly Love

Forgotten Colorado Silver: Joseph Lesher’s Defiant Coins by Robert D. Leonard Jr., Ken Hallenbeck, Adna G. Wilde Jr.

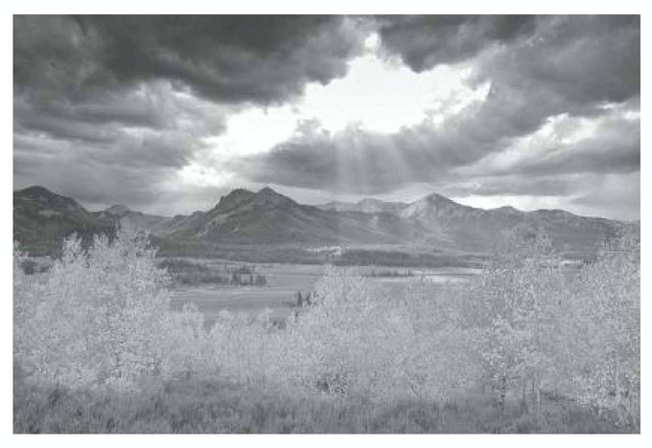

At the turn of the last century, miner Joseph Lesher attempted to raise the price of silver by privately minting octagonal “Referendum souvenir medal” coins with values of $1.25 or $1. They were common in Victor, Cripple Creek, Denver and other places in Colorado in the days after William Jennings Bryan fought unsuccessfully for free silver. Surviving an initial dust-up with the Secret Service, Lesher found a loophole to place them in circulation in 1900 and 1901. Today, coin collectors pay more than $1,000 for one. This is the story of Joseph Lesher and his audacious private mint, along with the merchants in the mining towns and elsewhere who supported him. You can find this book here!

The Land Before Fort Know by Gary Kempf

Known as the home of Mounted Warfare, Fort Knox is also the location of the U.S. Treasury Department Gold Vault that opened in February 1937. Fort Knox covers 178 square miles and spans parts of Hardin, Meade, and Bullitt Counties. The area was once home to Thomas Lincoln, father of the nation’s martyred 16th president, as well as the burial place of Abraham Lincoln’s grandmother, Bathsheba Lincoln. Images of America: The Land Before Fort Knox illuminates the past while images bring to light people and places of yesterday. You can find this book here!