The Underground Railroad was an amazing network of people and passages that helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and even to Canada. It’s a Pulitzer-winning novel, too.

But the Underground Railroad was also a series of real locations, run by real people. Those people often kept few records — the less that was known, the safer it was. But they helped many fugitives in the time before emancipation.

In the modern era, historians and researchers have been able to verify some of the locations and people. Here are five actual houses from the Underground Railroad, along with some stories about them and their residents.

Ohio

Alexander McCracken, whose home is pictured here, lived in Cambridge, Ohio, where he worked as a tanner. McCracken would transport fugitives north by wagon, often using Birmingham Road — until one night it was discovered that a spy lived on that road. McCracken had fugitives lie as flat as possible in the back of his wagon, covered them with a buffalo robe, and went three miles out of his way to outwit the spy. The fugitives were safely delivered four miles north of Cambridge to the home of Daniel Broom, another participant in the Underground Railroad.

Pennsylvania

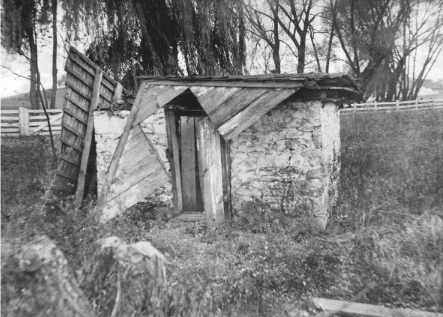

image from Slavery & the underground railroad in South Central pennsylvania, page 125.

This early twentieth-century photograph shows the spring house that sat near the home of the Woods family. The family, as one member later recalled, was “greatly troubled [with] what to do . . . for part of the [slave hunters’] program was to search the house and take off the Negroes. Finally they hit upon a plan to put a bed in the loft above the Spring House and hiding them there.” So that’s what the Woods did. It was an effective approach — especially one afternoon in 1863, when about half a dozen Confederates on horseback arrived at the Woods farm to search for fugitive slaves. “They all went all over the farm,” one of the Woods family recalled, “through the barn, and up the paddock.” Most frightening was when the horsemen watered their mounts at the springhouse, while a hidden African American women watched from within the springhouse. It was a close call, but she survived.

New York

Stephen Keese Smith was one of the leading Underground Railroad agents in Clinton County and hid fugitives from slavery in the barn behind his farmhouse, pictured here. Smith later stated:

Samuel Keese [my uncle] was the head of the depot in Peru. His son, John Keese, myself, and Wendell Lansing were actors. I had large buildings and concealed the negroes in them. I kept them, fed them. Often gave them shoes and clothing.

Vermont

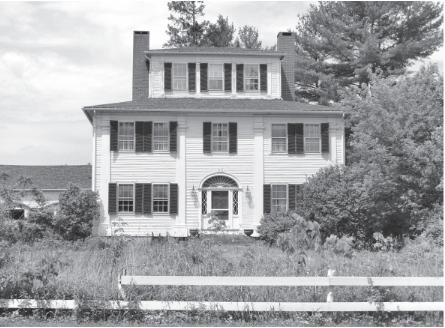

For years, the Sanborn house, pictured here, was known locally as an Underground Railroad stop. Locals still talk about the house’s underground tunnel. Fugitives would use a hidden door in the summer kitchen to get to the root cellar. From there they could follow the tunnel to the Sanborns’ barn, near the back of the property. The system made for easy, unseen wagon pickups. Many years later, local children would play in the underground tunnel, until it was blocked for safety reasons in the 1940s.

New Hampshire

Irenus Hamilton, whose home is pictured here, was a deacon in the Lyme Congregational Church. He was also a key player in the town’s (and church’s) slice of the Underground Railroad. In 1935, a Lyme resident named Caroline Fairfield explained the system in a letter:

Lyme was in those days an “Abolition” town from the minister down to the plain man voter. . . . The minister’s boys and Dea[con] Hamilton’s boys [would] tell of their experiences as runners from one station to another of [the] “Underground Railway.” The old parsonage was the first station in the village. Father F’s was next, and then Dea. Hamilton’s.