Napa Valley is known for its wine and winemakers, but just beneath the fertile soil lies another, more complex version of its history. One intrepid historian took her hometown to task to uncover the stories that for too long have been conspicuously absent in the region’s story of itself.

The following story is excerpted from Hidden History of Napa Valley by Alexandria Brown. Brown is also the author of Lost Restaurants of Napa Valley. Listen to an interview with author on the Rice Family and her research here.

Struggle & Progress in the Early Days of California’s Statehood

In 1850, California was inducted into the Union as a free state, but racial equality was far from settled. Antislavery legislation was inconsistently enforced—if it was enforced at all. No laws prevented slaveholders from bringing their slaves to California based on false promises of freedom, nor were there any limits as to how long a slaveholder could sojourn in California with his or her slaves. One of the most common ways to bring enslaved African Americans into California was through a bondage or indenture contract. An agreement was made between slaveholder and enslaved person wherein the latter would agree to work for a set amount of time or to earn his or her purchase price. When the terms of the contract were met, the slave was freed—or was supposed to be freed.

Nathaniel and Aaron Rice tested Napa County’s tolerance for slavery in 1860, when they went up against slaveholder William Rice. Rice inherited Robert and Dilcey and their son and daughter-in-law Aaron and Charlotte and brought them from the North Carolina cotton plantation where all four of them were born to Missouri. In 1859, William Rice and his family set out for California along with Robert, Dilcey and Aaron and Charlotte and their two sons, Nathaniel and Lewis. Shortly after arriving in Napa, William Rice freed Aaron, Charlotte and Lewis but not teenaged Nathaniel. What must it have felt like to be a child brought to an unfamiliar land and then torn from your family by a man who did not care at all about your welfare?

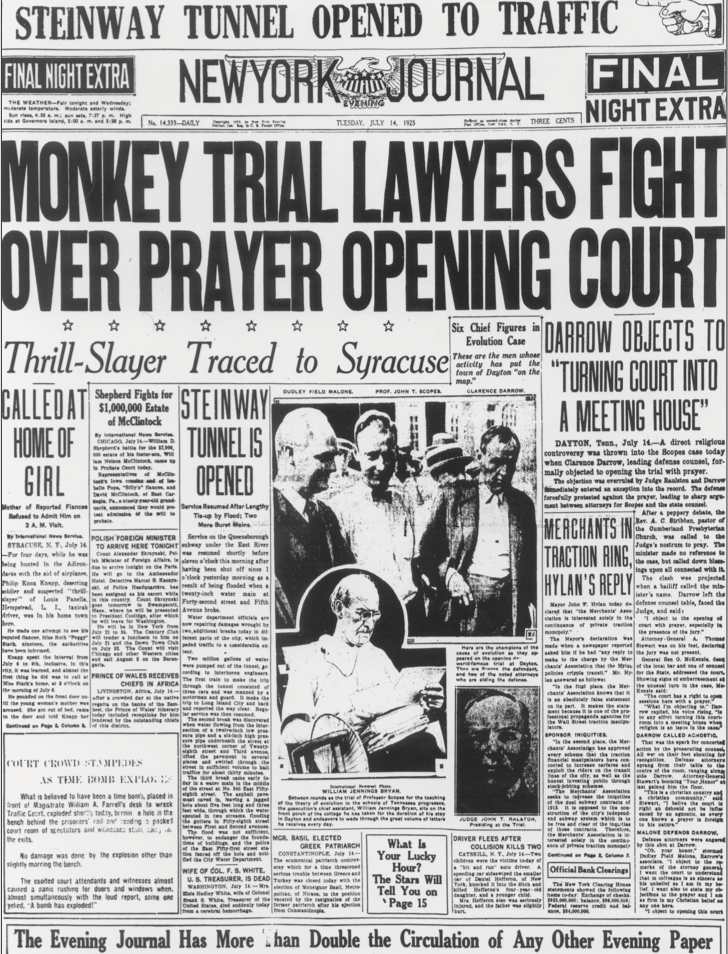

Nearly all the slave cases brought to the California courts in the 1850s were instigated by free African Americans who pooled money together to pay for legal expenses, hired white lawyers to defend the enslaved and submitted petitions for a writ of habeas corpus (a court order requiring the accused to produce the imprisoned person so the court can determine if the imprisonment is valid). Aaron did just that and tried to rescue Nathaniel. William Rice was arrested, but because state law barred all people of color from testifying in court, the justice of the peace threw out the case. Not only did William retain his contract over Nathaniel, he also sued Aaron for perjury by claiming Aaron and Nathaniel had lied about being coerced into a bondage contract. Yet again, Aaron was denied the right to testify, and the justice of the peace saddled him with a bail of $500. Prominent Black Napans Edward Hatton and John Sinclair paid Aaron’s bail. Nathaniel remained under William’s control for a while longer but was eventually freed.

Finally free, Aaron Rice and his family settled into life in Napa. Robert purchased a large farm near what is now Napa State Hospital, and the family ran it together for years. Robert also frequently preached at Napa’s African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) church. Sadly, Lewis died of tuberculosis in 1862; he was not yet twelve. When African Americans won the right to vote, Robert, Aaron and Nathaniel were among the first in the county to register to vote. Nathaniel married twice, first to Rebecca, who died of tuberculosis in 1875, then to Annie Elizabeth Dyer, Edward Hatton’s stepdaughter. Robert passed away in 1875, followed by Dilcey a year later and Charlotte two years after that.

William Rice relocated to Walnut Creek two months after the 1860 court cases against Aaron and Nathaniel; he died there in 1885. His widow, Louisa, somehow convinced an almost eighty-year-old Aaron to move into her mansion as her live-in servant. Aaron may have continued living in the house after Louisa died and her daughter Zarrissa Hill inherited it. Aaron Rice died in 1905, but rather than being interred at Tulocay Cemetery with the rest of his family, he was buried at the Alhambra Cemetery in Martinez down the hill from William Rice. Nathaniel moved in with the Canners, another family of formerly enslaved African Americans living in Napa, and died sometime shortly after 1900.

Other than that of the Rices, there is little known history about the first Black pioneering families in Napa. Some will never have their stories told, like “Negro Billy” and “Negro Girl C,” two African Americans listed on the 1852 state census, but some information is known about others. The earliest on record is Elizabeth “Lizzie” Brooks, who arrived in 1849 at sixty years old and lived in town for another forty-five years.

Abraham Seawell and his sister Matilda were enslaved first in Tennessee and then in Missouri before arriving in Napa around 1857. Once in California, Abraham married Judy, another newly freed African American, and eventually ran a two-hundred-acre farm in Napa. Both Abraham and Matilda were well liked by Napans of all races and were pillars of the Black community.

Hiram Grigsby was born into slavery in Tennessee around 1824 and arrived in California in his thirties. Hiram married Anne Hurges, a widow from New York who worked as a cook, in 1861. By the end of the Civil War, he had forty head of stock on 30 acres, and six years later, he acquired 133 acres just west of Yountville. In 1873, he, like thousands of other former slaves, placed a newspaper notice requesting information on his wife and children; they were named Patsey Stokes and Margaret, Amos and Hiram Jr., respectively. He had not heard from them since they were all enslaved in Pulaski County, Missouri. It is unknown if he ever reunited with them.

Paul Canner was born enslaved in Missouri. Once freed, he used the money and livestock he was given to head west; he arrived in the valley in 1856. Paul and his wife, Julia, lived on a ranch in Dry Creek, where he hauled tanning bark and worked as a teamster for neighboring ranchers. A few years later, the Canners relocated to Napa to ensure their children would get a good education. Tragically, several of their children died from tuberculosis contracted during an outbreak in the 1890s. Matthew died in 1894, followed by Richard and Polly in 1897 and Polly Ann in 1902. In 1862, Den Nottah, an African American man living in Napa, recorded 43 Black people in Napa city alone, including “8 farmers, 2 blacksmiths, 2 carpenters, 3 barbers, 5 wood speculators and poultry dealers, 4 jobbers. There are 13 families; 9 of them own the houses they live in.” Pioneering Black families, both free people and former slaves, were staking their claim on the valley.,

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Alexandria Brown grew up in Napa and attended Mills College, San José State University and Adams State University. She has a MS in library and information science and an MA in U.S. history. She was the head of the Research Library at the Napa County Historical Society and is currently on the board. She is a high school librarian and writes for Tor.com. In everything she does, diversity, equity and inclusion are at the forefront. Alexandria lives in the North Bay with her pet rats and ever-increasing piles of books. She can be found on Twitter (@QueenOfRats) and on her blog (www.bookjockeyalex.com).