Do you believe scientists? It’s a hot topic lately as we grapple with a global pandemic. Strangely, Americans have a long tradition of mistrust towards the scientific community — just look at climate change deniers, conspiracy theorists, anti-vaxxers, and the classic flat-earthers. Some of us just can’t be convinced! And sometimes, secularism and spiritualism meet at a crossroads to duke it out…

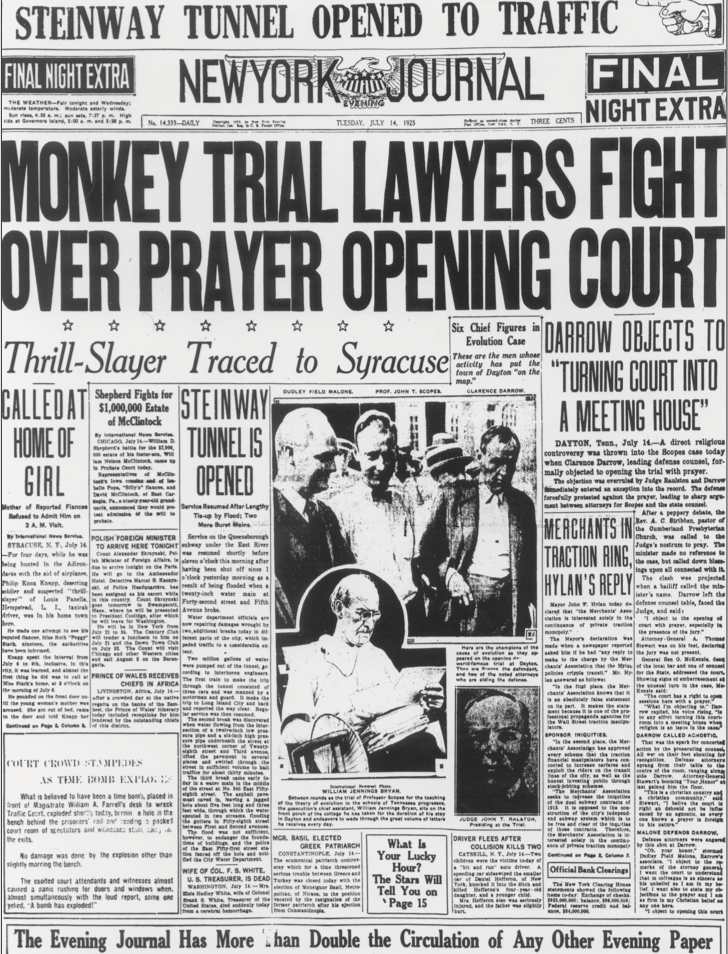

The Trial of the Century — what an irresistible title. Before OJ, before Michael Jackson, before the Manson Family, and even before the Lindbergh kidnapping, there was the Scopes Monkey Trial. While it may not sound as sensational now, the 1925 court case would test Tennessee’s ban on teaching evolution and would capture the attention of the entire nation. Formally known as the State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes, the Scopes Monkey Trial was America’s first “trial of the century” captivating the world and inspiring countless newspaper articles, documentaries, books, speeches, sermons, and a few political careers.

Desperate Businessmen

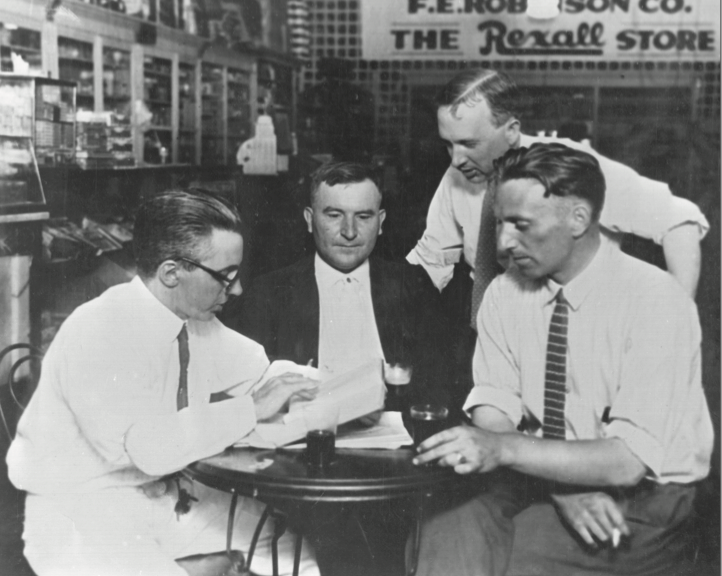

In May 1925, a group of Dayton businessmen hatched a plan to get some attention for their struggling, small town. They gambled that a show trial could test Tennessee’s newly passed law banning the teaching of human evolution, and certainly stimulate the local economy during the proceedings. Their contrived publicity stunt would bring the nation’s attention to the sleepy and stagnating community. Substitute teacher John Scopes agreed to the idea, and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), in the group’s first major trial, signed on to help underwrite the defense. Dayton became a virtual circus with vendors hawking hot dogs, lemonade, and all manner of books on biology and religion. (Spoiler: No monkeys were harmed.)

The Prosecution

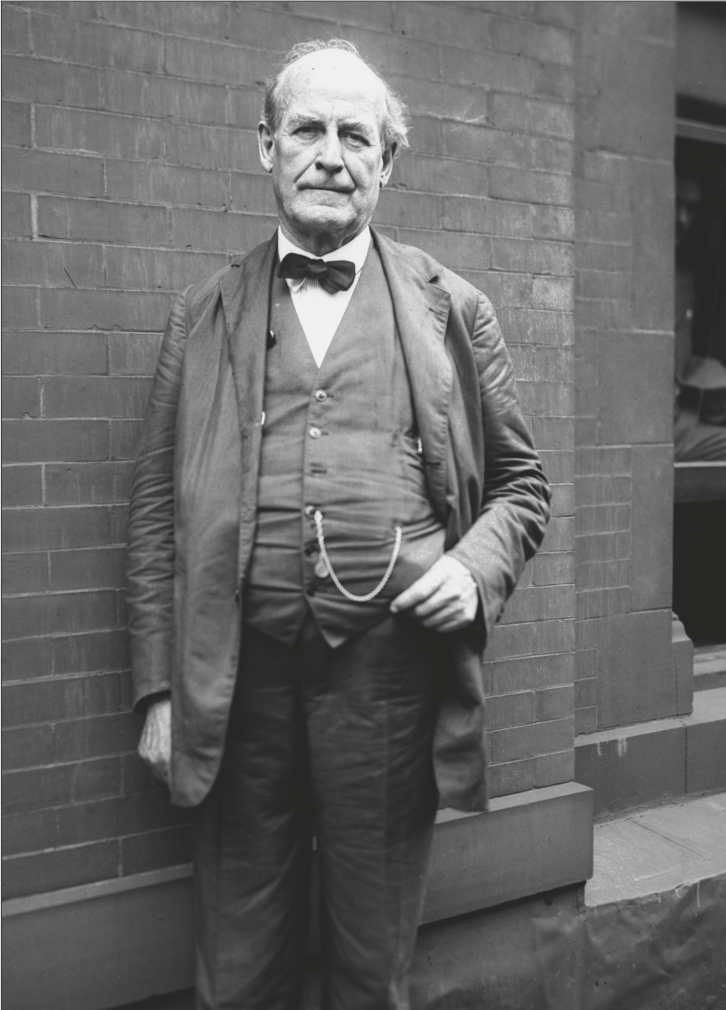

Populist politician and former congressman, secretary of state, and presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan had championed women’s suffrage and a progressive income tax. He was well-respected and popular, and, maybe cynically, the trial could be the first step in the upcoming war to restore America’s “morality.” Bryan knew a wedge issue when he saw one and declared the case was “not a joke but an issue of the first magnitude…[and would expose the] gigantic conspiracy among atheists and agnostics against the Christian religion.” Could this be his last shot at getting to the White House?

The Defense

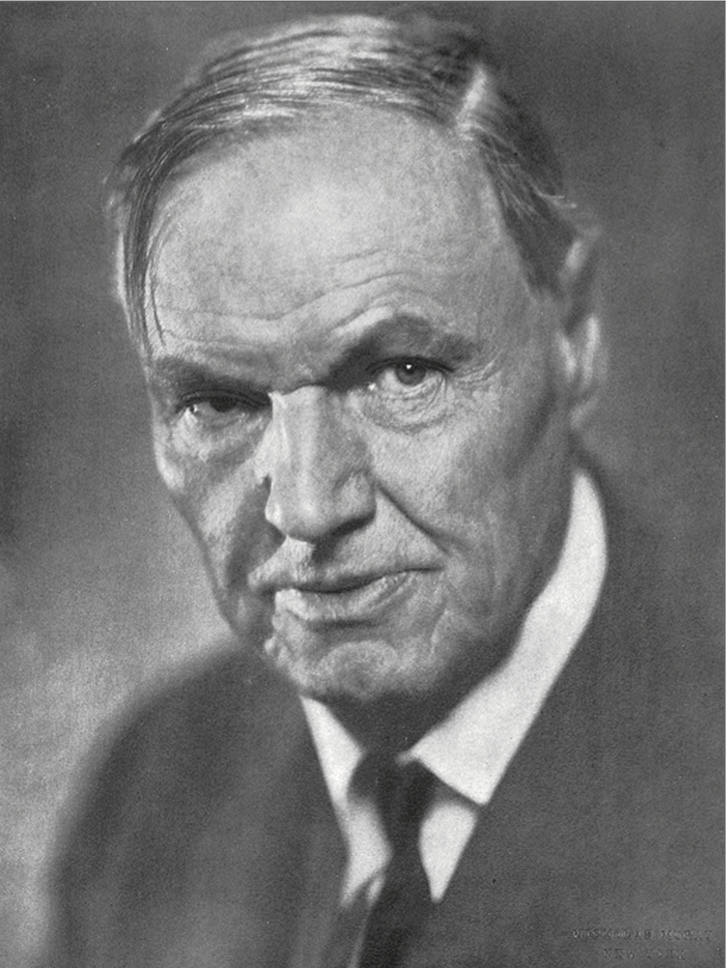

Famed criminal defense attorney Clarence Darrow volunteered for the case the day after Bryan announced his involvement in the trial. Ironically, the defense didn’t focus on whether Scopes broke the law teaching human evolution, but instead on the perceived threat to individual liberty. Ultimately, the two sides clashed over who decides what is taught in public schools and does religion itself

“We don’t need anybody from New York to come down here and tell us what [the Butler Act] means…The most ignorant man in Tennessee is a highly educated, polished gentleman [when compared] to the most ignorant man in some of our northern states.” – prosecutor Ben McKenzie

The Teacher

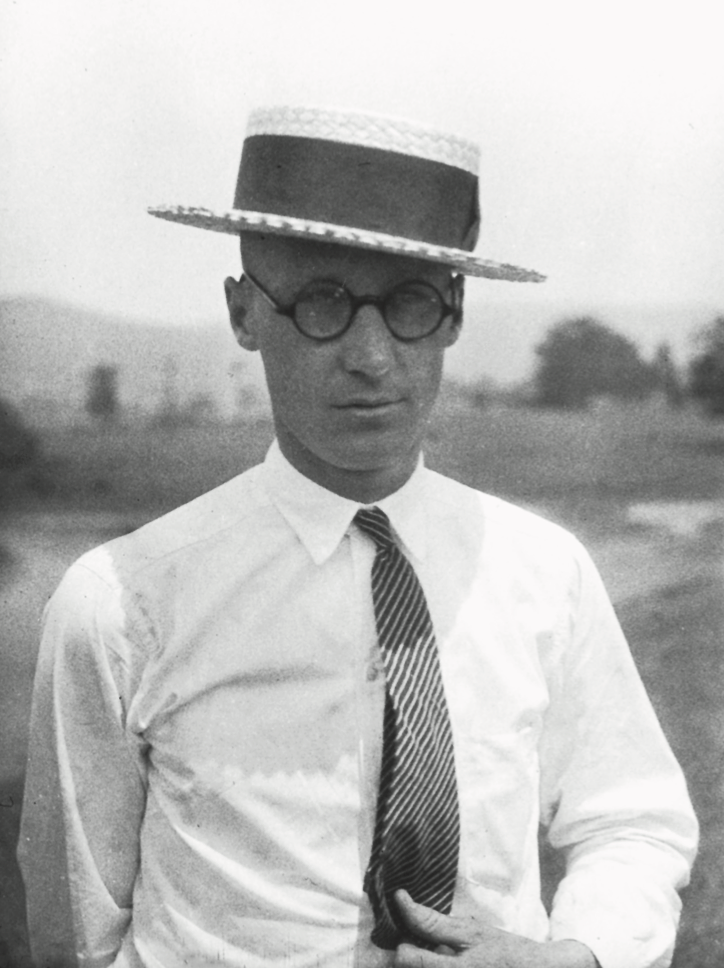

Poor John Scopes. He had no clue that this trial would become the most famous court case of his lifetime, testing the constitutional guarantees of liberties, and freedoms of speech and religion. The native Kentuckian, John Thomas Scopes became famous throughout the nation on radio and in newspapers, who willingly joined the custom-made media circus. After eight days, Scopes was found guilty and fined $100, which the ACLU paid. Scopes quit teaching, and the ACLU appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which ruled the Butler Act constitutional. The Tennessee legislature repealed the Butler Act in 1967.

“Your Honor, I feel that I have been convicted of violating an unjust statute. I will continue in the future, as I have in the past, to oppose this law in any way I can. Any other action would be in violation of my ideals of academic freedom, that is to teach the truth as guaranteed in our Constitution, of personal and religious freedom. I think the fine is unjust.” – John Scopes

Out of the spotlight, Scopes settled down to raise a family in Shreveport, Louisiana, working in the oil and gas industry. He lived there until his death in 1970. Both Shreveport and Paducah, Kentucky claim Scopes, but the former schoolteacher called Shreveport, not that far from the Tennessee courtroom, his hometown.