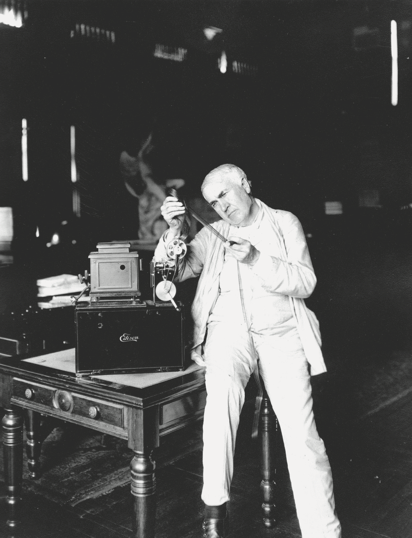

Who comes to mind when you think of innovators in the movie business? Spielberg? Hitchcock? Chaplin? What about Thomas Edison? Following breakthroughs with the first phonograph, incandescent light bulbs, and the delivery of electricity itself, Edison made his indelible mark on one more technological revolution — motion pictures.

The Father of Motion Pictures.

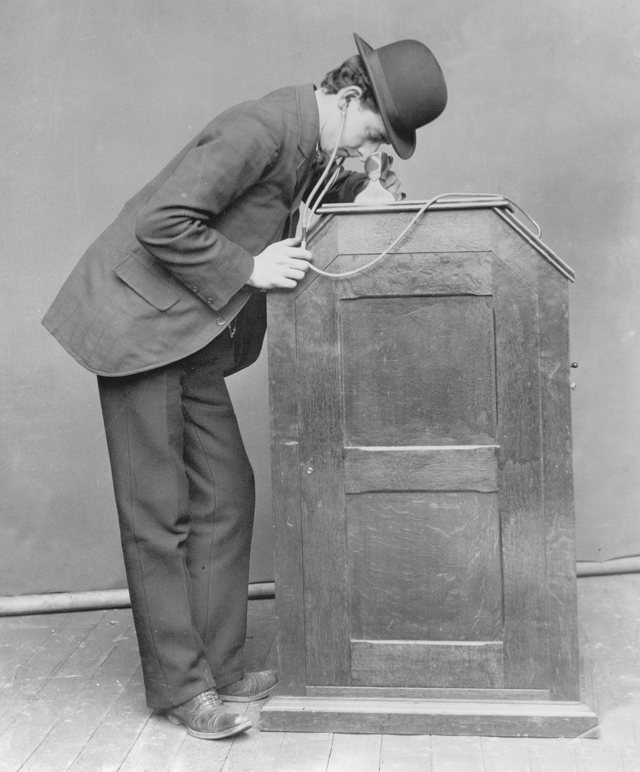

In 1876, Thomas Edison set up shop in Menlo Park, New Jersey, and by the end of the century, he had become arguably the most prolific inventor in history. With Thomas Edison’s company’s creation of the kinetograph (a motion picture camera) and the kinetoscope (a motion picture viewer), the public was able to view film that moved on spools, but these “movies” only lasted for about ninety seconds. In 1893, Edison presented the first commercial motion-picture machine at the World’s Columbian in Chicago. Later, Edison opened stores called “parlors,” where the public could spend a few cents to view these early movies in a kinetoscope. Edison and others improved the kinetoscope so that the movies could be enlarged and projected onto a screen. In 1896, Edison produced the first public showing in the United States. The movie business was born.

“Wizard of Menlo Park”

The world’s first motion picture studio was a small tarpaper-covered building with black interior walls. Dubbed the Black Maria, Edison’s studio produced films specifically for the use

Edison’s Edifices

Did Thomas Edison realize that one of the most celebrated public building styles would grow out of his moving pictures? There would be no cinema, no picture show, no movie theater without Edison’s entertainment. Among the most beloved buildings of the twentieth century are movie houses. Once his kinetoscope parlors found an audience, entrepreneurs leaped in to find ways to make a buck. Boston, Massachusetts proved to be the perfect site for this new form of entertainment. Always a theater town, Boston grew into a world-class cultural center because of its stages.

Boston’s Broadway

The history of Boston movie theaters is tied to a seven-block stretch of a narrow Downtown street. From the mid-nineteenth century, Boston’s main entertainment center was home to the Music Hall, then the huge Boston Theatre, followed by dozens of playhouses, dime museums, nickelodeons, vaudeville, and burlesque houses, and movie theaters and palaces. By the turn of the century, there were more than 50 theaters in Boston, most on or near Washington Street. By 1914, Boston was home to the 800-seat Beacon Theatre, the Boston Theatre (for live performances), the tiny Bijou, and B.F. Keith’s vaudeville house. Moviemakers were delivering 90-minute feature films, and opulent movie palaces of the era reflected the ambition of the new visual art medium. Technology was vital to staying competitive, and Boston would be the first to screen the first “talkie” to delighted audiences with The Jazz Singer.

Youngstown, Ohio: Theater Town

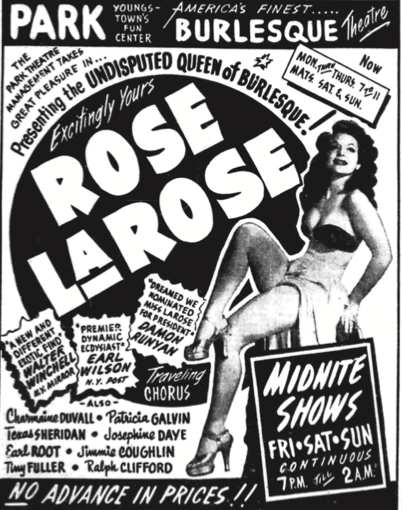

The central Ohio steel town fell for movies early in the twentieth century, and nickelodeons gave solace to

In decades following World War II, Steel Belt cities like Youngstown, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh fell into economic decline, and many of the grand theaters suffered neglect. Youngstown embraced the working-class art form of burlesque, which kept many old theaters open; but, as television grew in popularity, theaters shuttered. Even today, as the public’s viewing habits change with a plethora of competing screens, fewer and fewer landmark movie palaces remain on the American landscape.