Situated just a short walk from the White House Lawn, Lafayette Square is surrounded by landmarks and steeped in a fascinating history of rebellion.

The following stories are excerpted and adapted from Trouble in Lafayette Square: Assassination, Protest & Murder at the White House by Gil Klein, Foreword by John Kelly, Washington Post Metro Columnist.

“What is Lafayette Park? It’s a public space where, in times of national crisis, national anger or national exultation, crowds will gather, in front of the White House—protesters can be sure that the president will hear them.”

– John Kelly, Washington Post Metro Columnist

The Never-Ending Protest

From Chapter Twelve

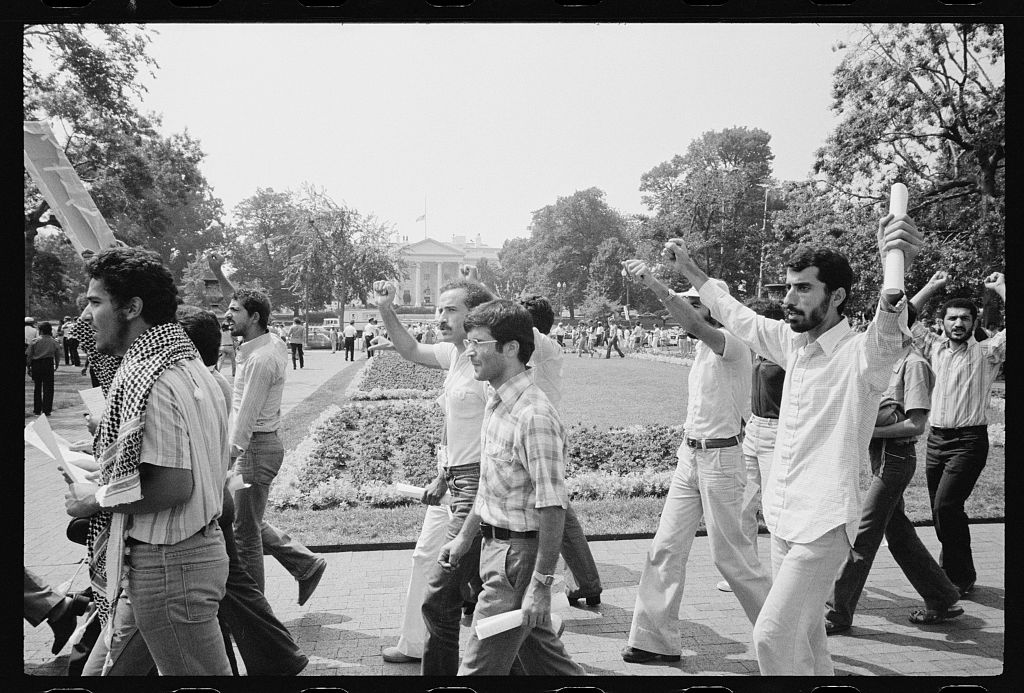

The women suffragists lit a fire both literally and figuratively that still burns today. When they took their protest for demanding the right to vote to Lafayette Park and the White House fence—including burning Wilson’s words in urns—they developed a tactic for political activism that has been embraced by American civil rights and antiwar groups. Even international activists seeking to draw attention to the plight of citizens in their homelands make regular appearances with their banners, chanting their slogans for freedom.

While protests that draw hundreds of thousands of people take over the National Mall and Ellipse on the other side of the White House, Lafayette Park is considered a more “personal venue” for demonstrators, according to the White House Historical Association. “Lafayette Park, as the front yard of the White House, played an integral role in bringing the government and the people within reach of each other. The president could not ignore what the people were saying.”

Not to say presidents didn’t want to ignore them.

As writer Roger McDaniel pointed out, “During the Gulf War, President George H.W. Bush was annoyed with an anti-war demonstration in Lafayette Park. An ‘incessant’ drumbeat used by protestors was so loud he ordered the drums silenced. ‘Those damn drums are keeping me up all night,’ Mr. Bush told a group of visiting congressmen. But a federal court held the park was a public place. The whole point of free speech was to get the attention of the President. The beat went on.”

Some sort of protest is happening practically daily. The National Park Service requires any group of twenty-five or more to obtain a permit before launching a rally in Lafayette Park. In 2016, that amounted to 114 permits, the same as the year before. That does not include protests on the sidewalk in front of the White House—another 26 permits in 2016. Not included is any group of fewer than twenty-five people. They can show up and exercise their First Amendment rights any time they want.

Alice Paul led her Lafayette Park protest for more than a year and a half. But that was just a blink of an eye compared to what a five-foot-tall Spanish-born woman by the name of Concepcion Picciotto endured. From 1981 until her death in January 2016, she and a small group of antiwar protestors held an around-the-clock vigil in the park across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House.

Alice Paul’s protests had a finite ending. When women achieved the right to vote, it was over. But Concepcion, who went by the name “Connie,” was calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the end to U.S. intervention in foreign wars. That’s a goal that may not have a resolution anytime soon.

Picciotto wore a helmet covered by a huge wig and scarf that framed her weather-beaten face. Only two teeth were apparent when she opened her mouth. When I interviewed her in May 2001, the twentieth anniversary of her vigil, schoolchildren were studying her poster that said, “Stay the Course and This Will Happen to You” with pictures of mounds of skulls, charred bodies and suffering people. In her constant battle with National Park police, she had become a lesson in First Amendment rights. “I’m going to be here until the government comes to its senses and eliminates the weapons of mass destruction and stops provoking wars,” she told the children. “There’s too much greed for money and control inside there,” she said, pointing at the White House. “They’re stealing money from social programs.” And that was before the Afghan and Iraq wars that started just months later and outlasted Concepcion’s life.

William Thomas began the protest on June 3, 1981, with a sign saying “Wanted: Wisdom and Honesty.” He was soon joined by Picciotto, and they created a makeshift shelter and squatted there, spelling each other around the clock, defying the Park Service that wanted them out. In the process, they became an institution of their own, a regular stop for school tour groups, whose leaders made them lessons in freedom of speech and the right to protest government policies.

As the Washington Post’s David Montgomery wrote in the Post on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the protest, “Take Lafayette out of Lafayette Square—the monumental statuary likeness of the Frenchman, with Colonial braid, big boots and a sword—and hardly anyone would notice. But get rid of the shelter made of a tattered patio umbrella, a weathered plastic tarp and those faded anti-nuke signs erected by Thomas and Picciotto? It wouldn’t be the same park.”

One thing they did accomplish was helping to pass what was known as Proposition One, which grew from petitions handed out by the vigil and led to an initiative approved by District of Columbia voters in 1993 that called for nuclear disarmament. Eleanor Holmes Norton, D.C.’s non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives, crafted the language of the initiative into a nuclear disarmament and conversion act, which she repeatedly introduced in the House—to no avail. “They want to keep the issue of nuclear proliferation and its potential terrible consequences before the public,” Norton told Gibson. “And they have chosen a prime spot to do it. … We won’t ever know what the success is, because it doesn’t have a specific end of the kind we are used to.

But that was not the end of the story—or the end of the protests. On an exceptionally hot July day in 2017, I wandered through Lafayette Park to see what was happening. Under the banner of the Hip Hop Caucus, dozens of protestors moved out of the park onto Pennsylvania Avenue. They represented such groups as the National Organization for Women, the ACLU and the NAACP. They were protesting what they saw as the Trump administration’s moves to suppress voter turnout that would diminish participation among minorities, the poor and the young. They waved signs that read, “End Voter Suppression” and T-shirts that read, “Election Protection.” A leader juiced up the crowd’s energy: “We’re saying you will respect our vote!” he shouted. “Everyone do me a favor, put your right hand in the air,” and the crowd responded. “Say, Power,” he urged. “Power,” they shouted back. “Say, Power,” he urged again. “Power,” they shouted back. “One last time, say it like you mean it so they can hear it in the building behind me. POWER.” And the crowd responded with a rousing “POWER.”

Demanding that the White House hear their rally for voter rights on the edge of Lafayette Park? Alice Paul would have been pleased.

Just a few feet away, a group of Chinese people held up banners with their own messages: “Chinese Communist Party Is Harvesting Organs from Falun Gong Practitioners,” read one. “Falun Dafa Is Great,” said another in both English and Chinese. Said a third, “Destruction of CCP [Chinese Communist Party] Mandated by Heaven. Quitting the CCP Is Helping Oneself.”

Tourists mingled among the protestors. Take a picture of Junior in front of the White House, get a shot of Sis with Lafayette’s statue. Get a family group shot with some protestors. It was all part of the Washington experience. And along the fence separating the White House from the crowd, uniformed Secret Service and White House police, seemingly more heavily armed than in years past, watched warily. In the past year, some people had leapt over the fence to gain entry to the grounds. One had made it all the way into the East Room. Another makeshift barrier had been set up to make it harder for people to reach the main fence. Skateboarders, strollers and rollerbladers had largely disappeared from the avenue. The guards seemed more willing to push people back, close the avenue entirely by extending “Do Not Cross” tape.

But what is that on the sidewalk, behind the voting rights protestors, next to the Chinese Falun Gong? It’s the makeshift encampment with its signature tarps and signs warning of catastrophe unless nuclear bombs are banned. Eighteen months after Connie’s death, the nation’s longest protest continues. Sitting on a wheelchair in the heat is Philipos Melaku Bello, his long dreadlocks tied under a knit cap, a big smile of welcome on his face. He’s glad to see you. He says his father was Thomas’s good friend and his godfather. He has been involved in the protest off and on since its inception, as well as antiwar rallies in other parts of the country. When he saw Connie’s health declining, he said, he started coming every day.

He insists he does not have a political agenda, just an agenda of peace. “I am not a left-winger or a right-winger,” he says. “I’m here because I stand up for humanity. I love the civilians of the planet, and I don’t believe any civilian should be targeted by any nation’s military in an act of war.” After the death of Picciotto, Philipos Melaku Bello took over leadership of the thirty-four-year-old antiwar protest across the street from the White House. He says he logs about one hundred hours per week.

It is getting harder to maintain the vigil, he says. At one time, it had nineteen volunteers so that no one had to do more than three shifts a week. “One of the volunteers just quit, so now there’s me and two others. One does 38 hours a week and one does 30 hours. There are 168 hours in a week, so I do 100.” But he says he will keep going as long as he can. After all, he comes from a good pedigree.

“Do you remember the Drums of Thunder in 1991?” he asks of the protest that drove President George H.W. Bush to distraction. “That was us and a lot of my friends.” A big smile crosses his face.

Sometimes it’s hard to hear Philipos because behind him a woman with a sign that identifies her as evangelist Melodie Crombie is preaching and singing into a bullhorn. With police restricting access to the avenue, it’s gotten a little tight along the sidewalk. But as I move north from the avenue away from the White House, the hubbub starts to die away. Even in the heat, people are sitting on benches in the shade, chatting and relaxing. The Bernard Baruch bench still offers a spot for inspiration.

Yes, all is peaceful in Lafayette Park—until it isn’t.