August 18, 2020 marks 100 years since Tennessee became the 36th state to pass the 19th amendment, officially adding it to the constitution. The fight for woman suffrage was a long-fought battle the produced some of the most fascinating feminist leaders in our history. But the road would have looked very different if Tennessee State Representative Harry T. Burn—the youngest ever elected to the Volunteer State assembly—had not voted his conscience.

And he very well may not have been pushed to do that had it not been for the timely delivery of a letter from his mother, Febb Burns, the morning of the vote that changed the course of history.

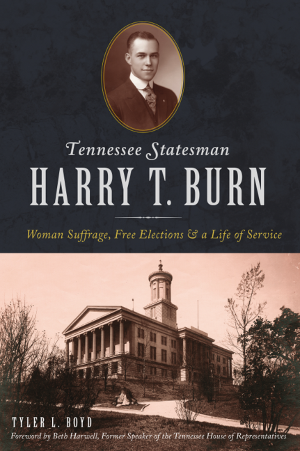

The Following is an adapted excerpt from Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn: Woman Suffrage, Free Elections & a Life of Service by Tyler L. Boyd.

McMinn County was divided on the issue of suffrage. Febb Burn did not engage in political activism, but she knew most of the principal suffrage leaders and was cognizant of the struggle to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. She subscribed to three daily newspapers.1 Before leaving to attend the special session, she told Harry that she wanted him to vote for suffrage.

On the fifth day of the special session, the State Senate voted in a landslide to ratify the amendment. Although pleased to learn of the Senate’s ratification, the comments of her own county’s senator disappointed her. State Senator Herschel M. Candler cast one of only four votes against the amendment. Blasting the idea of woman suffrage in his “bitter” speech, he warned of “petticoat government” should the amendment be ratified.

After reading the papers, Febb Burn sat down in her little chair on the front porch of Hathburn and wrote a “folksy” seven-page letter to her son. She included a message not of admonishment, but of motherly advice: “Hurrah and vote for suffrage.” Her other son, Jack, took the letter to the Niota Post Office and addressed it in ink to “Hon. H.T. Burn” in Nashville.

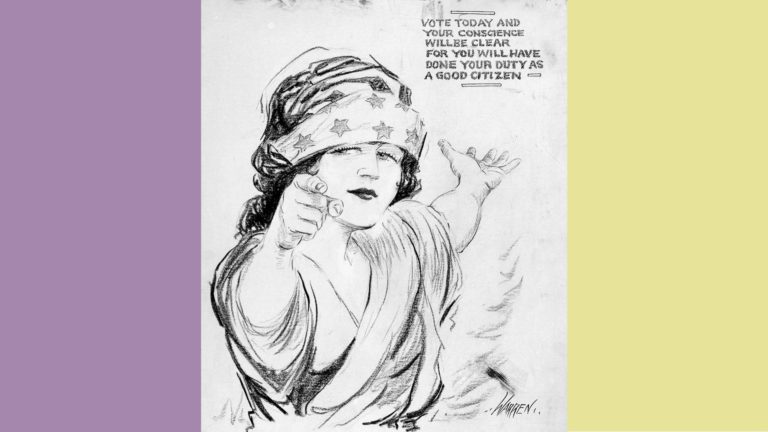

Harry T. Burn received the letter on the morning of August 18, 1920, the day of the fateful vote. Like her son, Febb Burn had a remarkable sense of timing. The young representative read the letter before the legislature convened that morning. The time had come for the Tennessee House of Representatives to take a vote. Would they concur with the State Senate’s action?

“Don’t keep them in doubt”

As he walked onto the House floor, Burn had pinned to his jacket lapel a red rose representing his intent to vote against suffrage. A member of the NWP in the gallery noticed his red rose and said to Burn, “We really trusted you, Mr. Burn, when you said your vote would never hurt us.” Burn replied, “I meant that. My vote will never hurt you.”

After the introduction of Senate Joint Resolution No. 1, Speaker Walker immediately moved to table it. One vote against tabling resulted in a 48-48 deadlock. Again, the Speaker called for a second vote to table the amendment. Again, deadlock. Burn, torn between his support for suffrage and his desire to punt the issue to the next regular legislative session, voted to table both times.

RELATED: “The Past is Female: Tales of the Suffragette Revolution”

His mother’s words “Don’t keep them in doubt” stuck in Burn’s mind. He had previously stated that he believed in suffrage. He had also previously stated that he wanted to delay action until the following legislative session in January (assuming he was reelected). He had told the suffragists that he would never hurt them and that he would vote for the amendment should it need his help to be ratified. No one knew what he was going to do before he cast his vote. Many suffragists doubted his reliability. But he had finally made a decision. He was about to remove their doubt with his impeding vote.

Hoping to kill the amendment for good, the House Speaker called for a vote on the “merits” of the resolution. This was it. No more tabling or delaying tactics. If the resolution failed to receive a majority this time, it was dead in Tennessee, maybe even in the country. Suffrage leaders would have had to find another state to lobby to become the “Perfect 36th,” a highly unlikely prospect in the imminent future.

The roll call began. Anderson and Bell voted aye. Bond, Boyd, Boyer and Bratton voted no. Next on the list was Harry T. Burn, sitting on the third row to the right of the rostrum.

An aye from Burn would put it over the top and enfranchise millions of American women. A no would kill the amendment, probably indefinitely. He had received several telegrams and letters for and against ratification. His district was split on the issue. His powerful mentor, State Senator Candler, vehemently opposed suffrage. Former U.S. Senator Newell Sanders had urged him to support suffrage. So had both presidential candidates. His mother had asked him to vote for ratification.

Remembering his mother’s words and following his conscience, Harry T. Burn cast the vote that changed the United States of America forever.

ABOUT THE BOOK:

Harry T. Burn’s great-grandnephew, Tyler L. Boyd, chronicles the life and legacy of a Tennessee legend in this never-before-told life story. After reading a letter from his mother, Burn cast the deciding vote to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granting suffrage rights to millions of American women. Born and raised in McMinn County, he served in Tennessee government in various capacities for many years, including terms in the state senate and as delegate to state constitutional conventions. His accomplishments include helping secure universal suffrage rights, drafting clean election laws and leading successful careers in law and banking. He encountered more controversies in his career, such as an unsuccessful gubernatorial bid, election fraud and implementation of state legislative reapportionment.