Pearl Beer is an iconic Texas brand and landmark, second only to the Alamo itself. While Tex-Mex cuisine has proven to be universally popular, many don’t see as easily that Germans and Bohemians have made essential contributions to the culture of Texas too. Tex-Germ anyone?

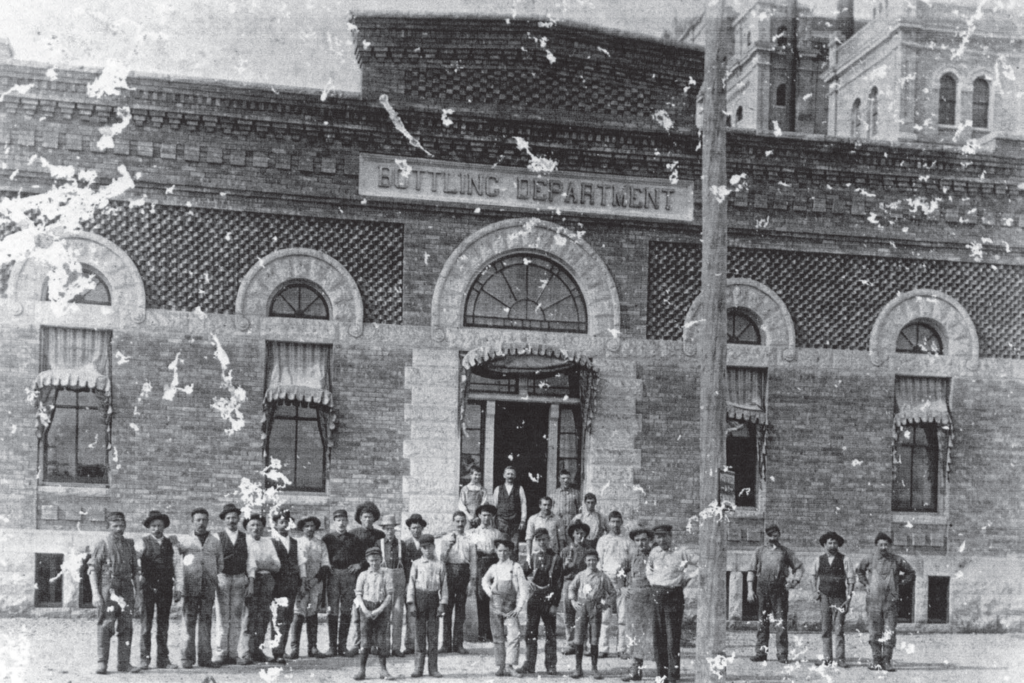

The Pearl story begins at the founding of the City Brewery in 1883. German and Bohemian immigrants, missing their beloved lager, sought to make the beverage in their new home. Previous local brewers were only able to produce ale, possibly due to lager needing colder temperatures — not any easy trick to pull off in central Texas. In 1887, a group of local brewers formed the San Antonio Brewing Association at the City Brewery, and later that year, Pearl lager beer was filling bottles and wooden kegs, making many happy Germans.

Pearl Beer was soon beloved in San Antonio, and thanks to rail, was enjoyed throughout the Lone Star State, even though not all of Texas was “wet.” Counties, precincts, and towns could decide for themselves if they wanted alcoholic beverages in Local Option laws starting in 1891.

In 1902, the colorful German immigrant Otto Koehler took control of the operations, made improvements to the facilities, hoping to get the beer beyond the Texas border. Following his death, Otto’s widow Emma Koehler oversaw the brewery surpassing rival Lone Star. With over 110,000 barrels produced per year, San Antonio Brewing Association became the largest beer maker in Texas.

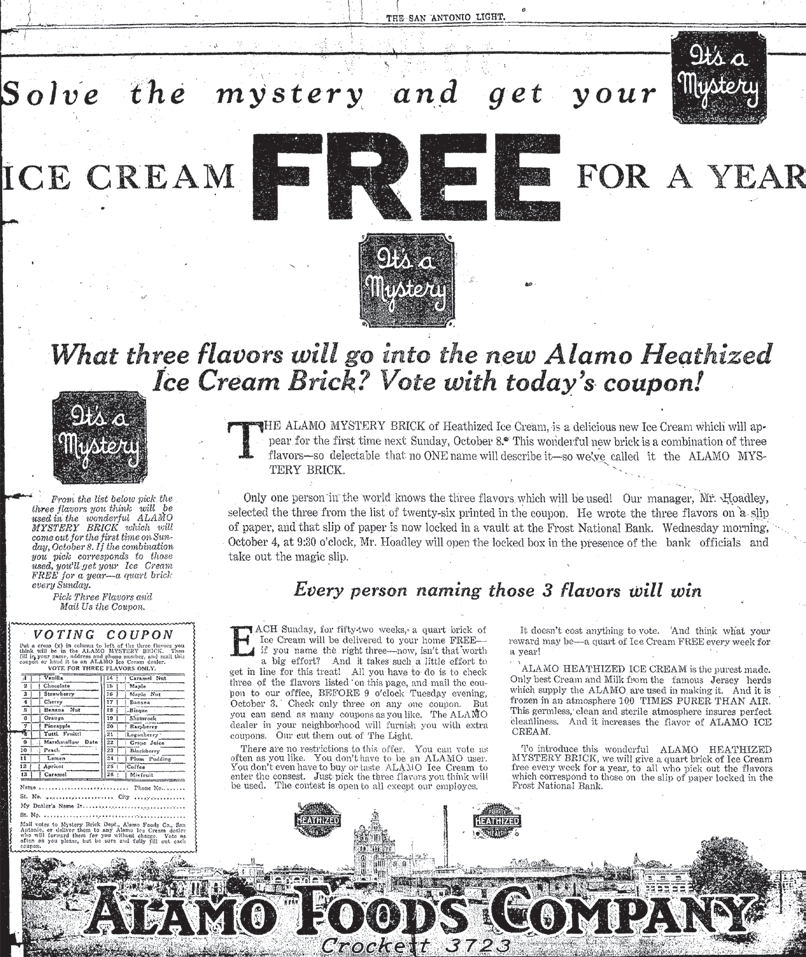

At the onset of national Prohibition in 1920, Otto’s widow Emma Koehler reorganized the brewery itself to make alternate beverages like soda, and products as diverse as dry cleaning and ice cream as a renamed Alamo Industries. In the decades following the repeal of Prohibition, San Antonio Brewing Association finally redubbed itself after its signature product — Pearl Brewing Company. Nephew Otto Koehler ran Pearl with the high standards of his namesake. Following his death, much of the German-immigrant spirit of this family business was lost. Waning sales and increased competition led to the company’s sale to Pabst in 1985. The out-of-state owner wasn’t able to maintain the Pearl brand, and neglected the beloved beer into oblivion. Or so sad Texans had feared…

A local billionaire came to Pearl’s rescue in 2002, restoring the facilities, including the landmark brewhouse, now home to the trendy Hotel Emma, and Southerleigh Brewing in the original Pearl bottling building. Today, the 22-acre property west of downtown San Antonio is a popular destination for locals and tourists. Not surprising for a town famous for historic preservation.

Truly, it would be impossible to imagine San Antonio skyline without the 1894 brewhouse smokestack.