Houstonians laugh that there isn’t any topography there. They’ll joke that it’s flat, like a table top. In reality, Houston has some natural features — you just have to squint to see them. Most notably, Houston boasts nearly two dozen low and slow-moving natural waterways called bayous. Some are channelized with concrete banks, some are restored to their natural appearance, but all are vital to keeping the swampy coastal prairie called Bayou City free from flooding… mostly.

On August 30, 1836, just months after Texas won its independence from Mexico, New York land speculators Augustus Allen and John Kirby Allen placed an advertisement in the local Telegraph and Texas Register bragging of their new “Town of Houston.” Their description of the area was highly exaggerated, and filled with downright lies. The biggest boast was that Houston was “situated at the head of navigation,” where Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou meet, and “at a point on the river which must ever command the trade of the largest and richest portion of Texas.”

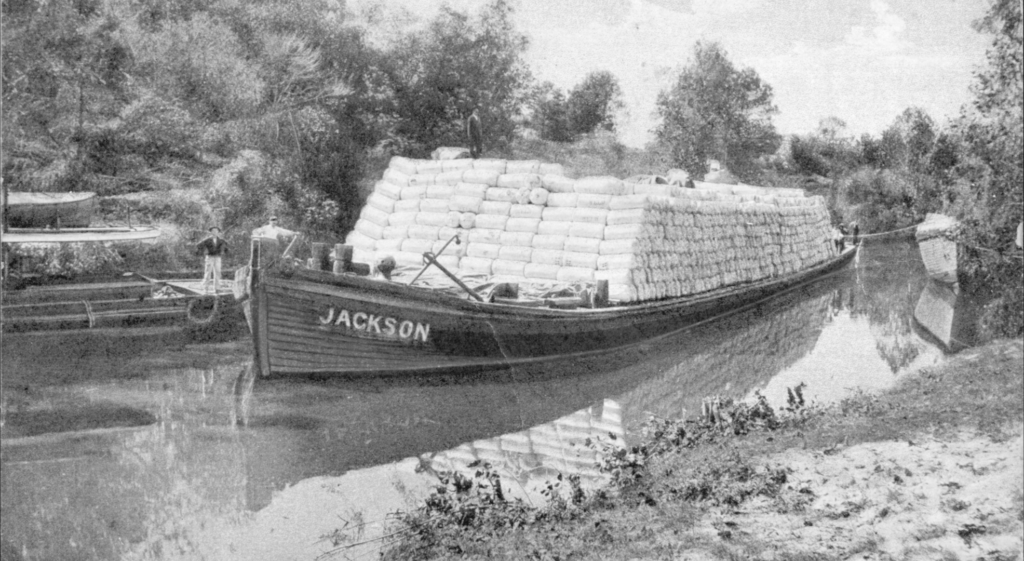

A few months after their colorful ad, the Allen Brothers hired a captain to see if a commercial ship could, in fact, make it all the way from the Gulf of Mexico, through Galveston Bay, and up to Buffalo Bayou. In January of 1837, the packet steamer Laura arrived at Allen’s Landing, the foot of Main Street, proving that Houston could be a port city. Local commercial enterprise was limited to regional activity until the years following the Civil War. When the new railroad network connected Houston to the nation, lumber and cotton could be shipped efficiently from the wharves along the banks of Buffalo Bayou. Dredging and widening the channel kept Houston competitive with Galveston. In the early 20th century, civic leaders would form the Houston Ship Channel, and made sure Houston received federal funds to build it. By 1914, the Ship Channel had been dredged to a depth of 25-feet, and today, it is a thriving, fifty-two-mile, 45-feet deep water port connecting Houston to the world.

Buffalo Bayou remains Houston’s signature waterway. It meanders its way from neighboring Ft. Bend County, into the western edge of Houston, through its most posh residential neighborhoods, through Memorial Park, into Downtown, then splitting industrial Houston on opposite banks, and finally out to Galveston Bay, providing access to the Gulf of Mexico.