In the early decades of the 1700s, France, Spain, Portugal, Holland, and England reached into all corners of the globe. While Spain arrived in the New World first, France and England soon followed and brought their centuries-long rivalries with them. France controlled lands in and around the Mississippi River, including the mouth at the Gulf of Mexico, and extended to the Red River to the west, where the Spanish state of la Provincia de Tejas began. But as the French and English colonies grew in size, Spanish King Philip V grew concerned that the French would creep further along the Gulf Coast into Spanish lands. In 1730, the monarch put out a call to his subjects, looking for volunteers to grow the colony in New Spain.

The Invitation

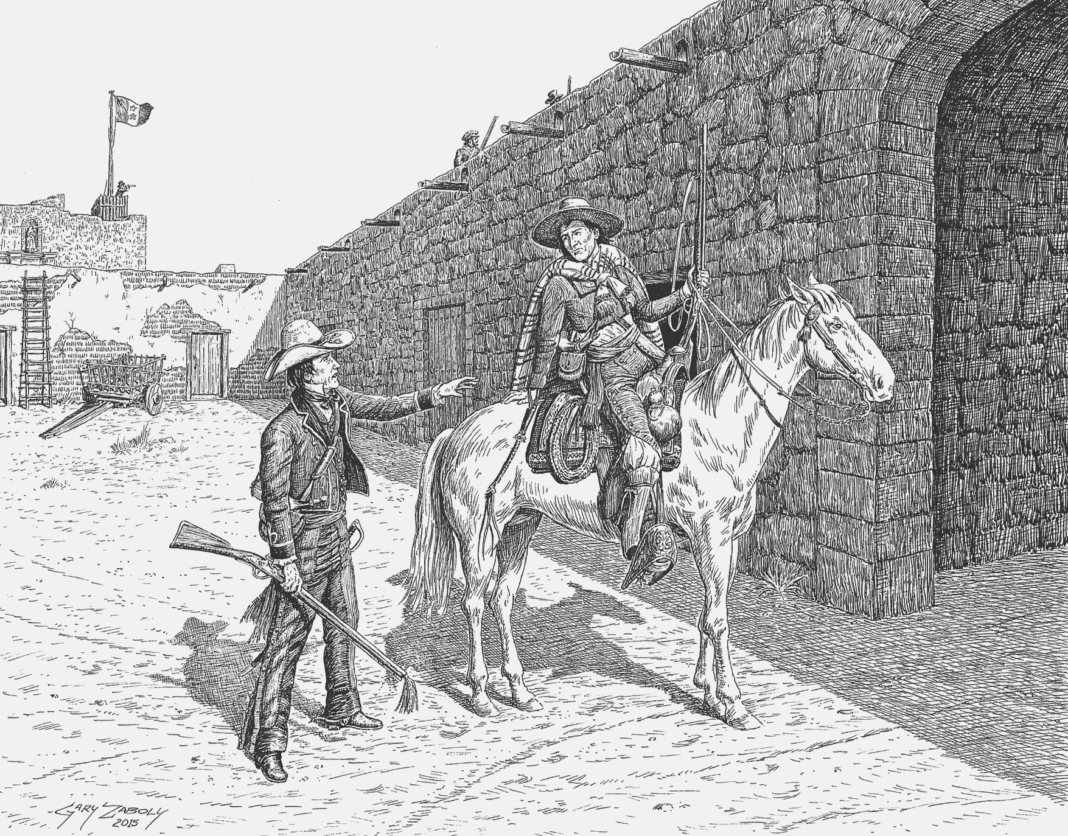

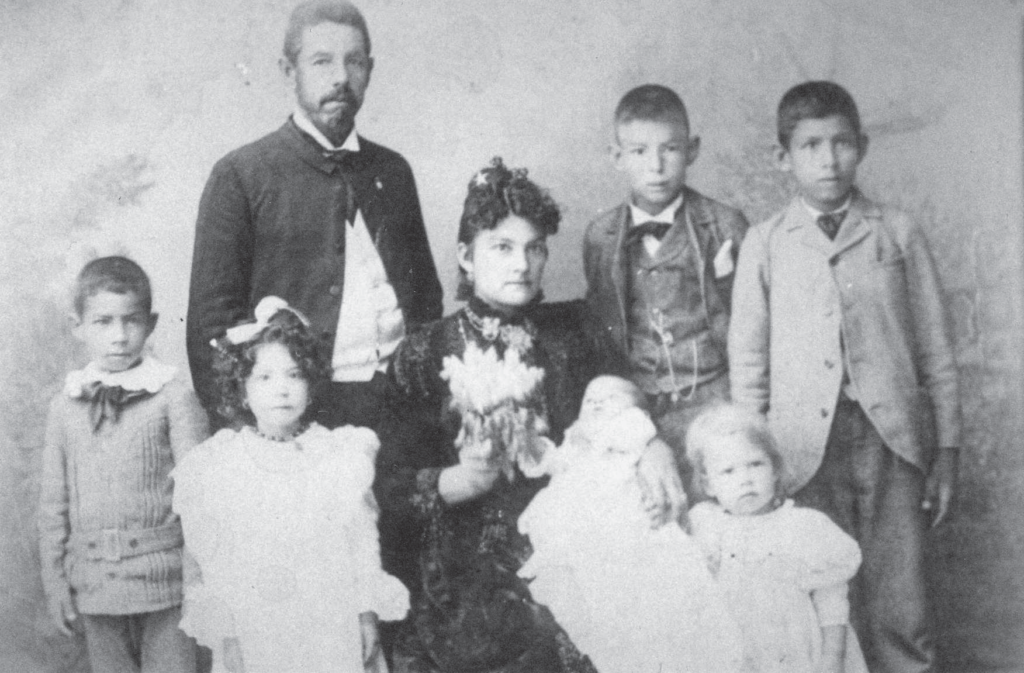

The Canary Islands are found 62 miles west of the African continent. Spain, the great sea power, colonized the islands by force, and fought the French and Dutch for control. The Spanish colony in present-day Texas had its share of missions, hoping to spread Christianity to the natives, and provide aid to early colonists on the lawless frontier. King Philip V invited Canary Island residents to emigrate to the small community in present-day San Antonio, Texas to deter French invasion. The king paid for travel expenses, and paid them more on arrival. The journey took the original 16 families across the Atlantic Ocean to Cuba, then on to Vera Cruz, Mexico, then up the Texas Coast, and on to San Antonio de Béxar, where the so-called Isleños would ultimately establish the first city government and permanent Spanish settlement.

The American Revolution

Mexicans’ participation in the American Revolution is well-documented, and the Canary Islands descendants played a part in defeating England. Possibly seeing a chance to reclaim French territory along the Mississippi River and the Floridas, Spain entered the fight against the British in 1779. From the Presidio de la Bahia, Louisiana Governor Bernardo de Gálvez ordered Texas cattle to be driven to the east to feed American troops on the front line — some of the local ranchers who supplied Gálvez were Canary Islanders.

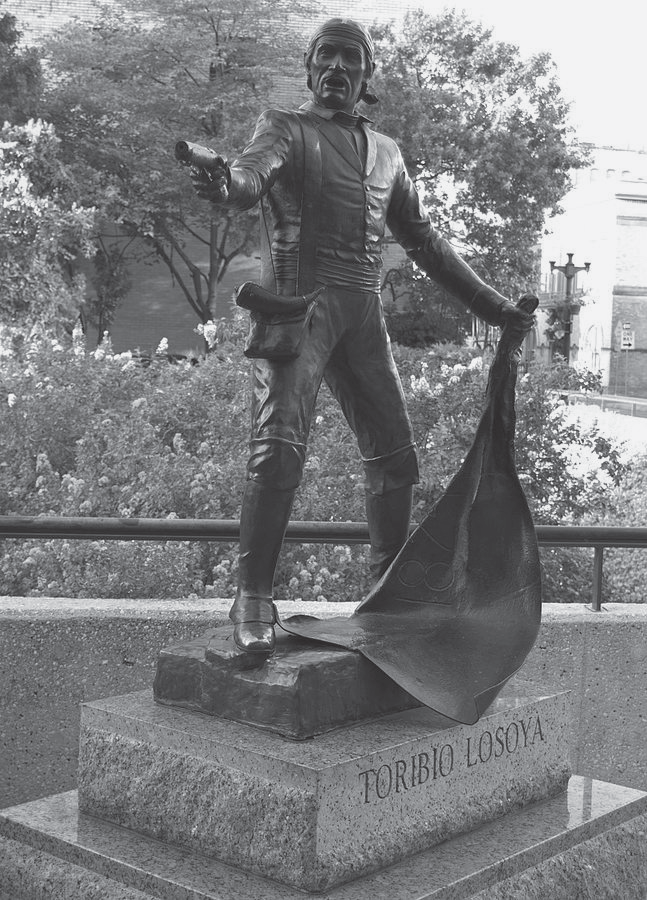

The Texas Revolution

A tragic irony following the Texas Revolution, was that even though Texas was ethnically Spanish for a hundred years before the Battle of San Jacinto, and Anglo and Hispanic Texans won their independence from Mexico together, bitter resentment grew from memories of Santa Anna’s orders to leave no survivors at the mission in Goliad. Tejano service to Texas was ignored or hidden. Decades later, before the introduction of railroads, ox cart traders, or carreteros, served a vital service for the state by carrying good from the coastal port of Indianola to central San Antonio, but they were often hassled or worse by Anglos. Ethnic segregation persisted, and racists clashes between the two groups intensified and continued well into the late 20th century.

Legacy

In contemporary San Antonio, the proud descendants of the Isleños formed the Canary Island Descendants Association to celebrate the original families courage and sacrifice with an annual events and advocacy programs. Several traced their family lines to the American Revolution — earning them membership in the prestigious group The Daughters of the American Revolution. They continue to ensure that the history of these pioneering Texans is protected.