The Early Years

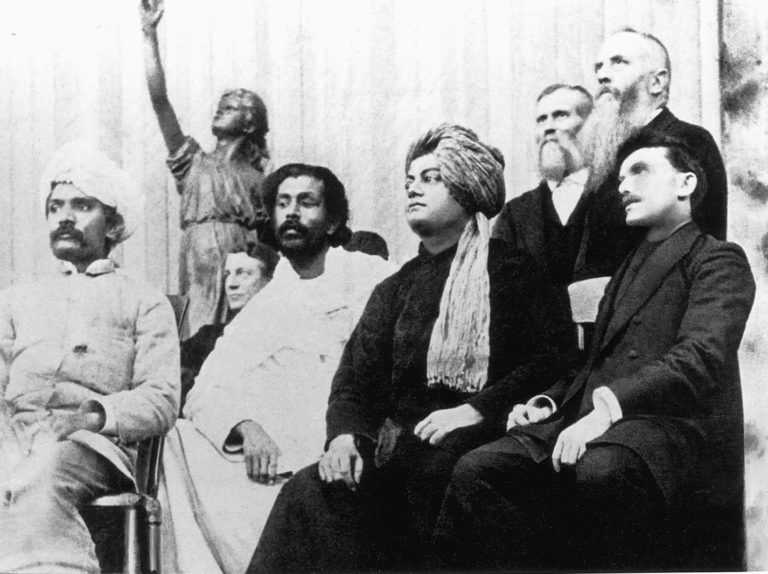

Long before the Asian Indian population growth in the mid-1960s, some famous Indians visited and left their mark on Chicago. Some notable visitors included the great Hindu philosopher Swami Vivekananda and Bengali Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore. After 1965, Indians arrived in large numbers and formed the first substantial Asian Indian population in Chicago. The selective nature of the 1965 immigration law gave initial preference to skilled professionals. But once established, these professionals sponsored their relatives and the community became much more diverse.

Family, Work, and Religion

During the 1980s and 90s, many Indian immigrants ventured beyond the institutions of their employers. They utilized their entrepreneurial energy, professional training, and global connections to establish international commercial and technical enterprises of their own.

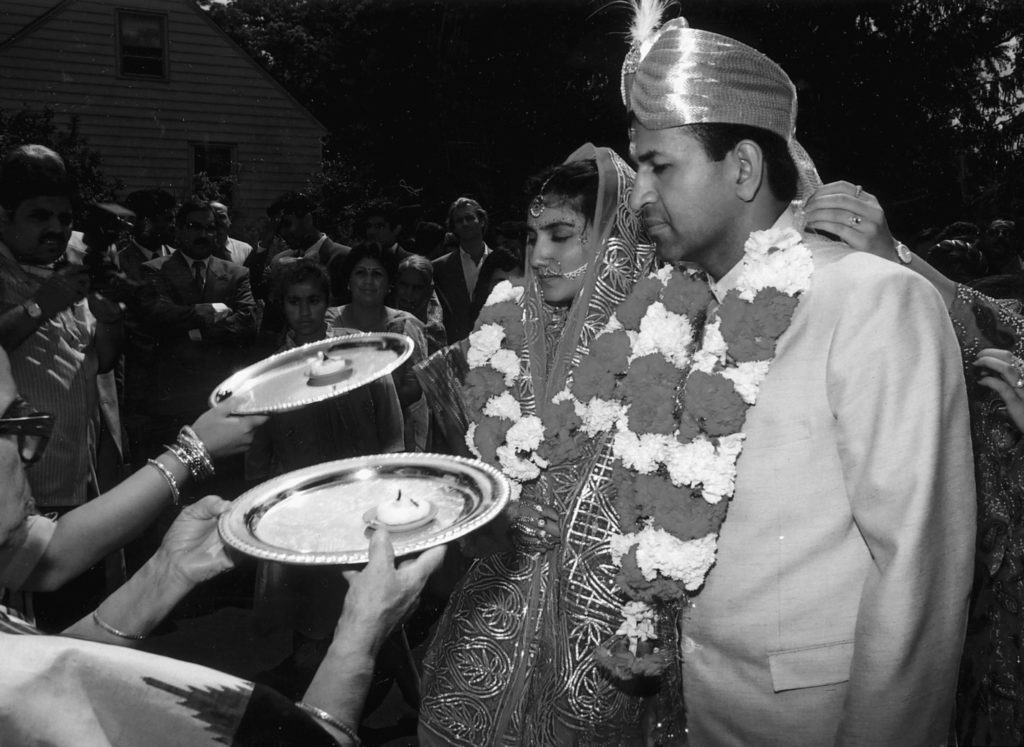

When Asian Indians arrived in Chicago in the 1950s and 60s, they looked to their fellow Indian colleagues to fill the void caused by separation from their families. They gathered together to celebrate each other’s birthdays, religious events, and holiday festivities. International phone calls were prohibitively expensive, travel to India was out of the question, and long letters to and from home were read, re-read, and cherished.

Beginning in the 1960s and 70s, Hindus worshiped in homes under a broad Hindu identity. As their numbers grew in the following decades, they regrouped according to narrower preferences. The result is a proliferation of temples dedicated to different deities in the Hindu pantheon.

Tradition and Community

Classical music and dance performances, plays, independent art films, and exhibitions of visual art help strengthen traditions. They inspire new forms of expression that celebrate the vibrant and varied cultural life of Chicago’s Asian Indian community.

The leading Indian political body in the city is the Indo-American Democratic Organization. Established in 1980, it has grown in influence by endorsing political candidates who seek the support of the Indian community, conducting voter registration drives, sending delegates to national political conventions, and teaming up with other ethnic groups to lobby on issues such as affirmative action, immigration, and discrimination.

Many Asian Indians who have prospered in the United States share their good fortune with others by volunteering and contributing generously to worthy causes. In addition to established mainstream institutions, which provide abundant avenues for service, a plethora of organizations addressing special needs and interests of immigrants has emerged as the population has grown. These organizations facilitate immigrant adjustment to America and American understanding of the distinctive heritage and customs of Asian Indians.

To learn more about the Asian Indian community in Chicago, click here.