Who were the Donauschwaben? According to stlmag.com, they were a German ethnic group that were victims of ethnic cleansing in Yugoslavia. Those who escaped found refuge in the United States after World War II. These German people lived in Chicago and other major American cities whom the American Aid Societies for the Needy and Displaced Persons of Central and Southeastern Europe tried to save after World War II.

A Humanitarian Crisis

The truth about Yugoslavian ethnic cleansing is what created the American Aid Societies for the Needy and Displaced Persons of Central and Southeastern Europe in the first place. Word had come to Chicago in late 1944 from Dr. Kaspar Muth, a senator in the Romanian legislature, and the word was bad. In Chicago; the Bronx; St. Louis; Milwaukee; Detroit; Cincinnati; Buffalo; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Mansfield, New Jersey; and Elizabeth, New Jersey, a long-standing community slowly emerged behind Nick Pesch and John Meiszner in the cause of humanitarian relief for the German refugees. This is nothing new among America’s Germans, as Melvin Holli proved when he brought the records of the German Aid Society, c. 1873–1896, to the Library of the University of Illinois at Chicago. People in America do “meet to talk about their needs,” and this participation in the political process includes the Donauschwaben.

Ready to Work

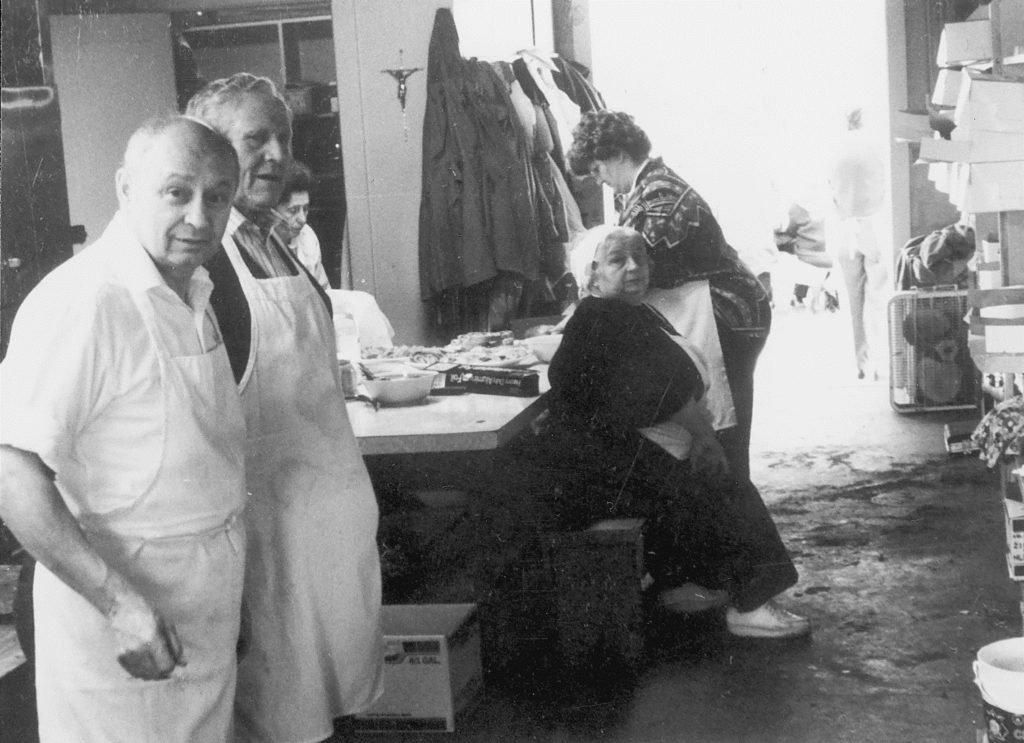

In 1949, Nick Pesch finally went to Europe to make a “first-hand” report from the refugee camps for the American Aid Societies. As founder and leader, he was the logical choice to go. He shot a silent film of this journey that was transferred to video in 1998 in the studio archives of J. Fred MacDonald, Professor Emeritus of Northeastern Illinois University, who noted that the message of the film seemed to be quite simple. The Danube Swabians were ready to work. This would be in perfect accord with their long pioneering heritage and represents a legacy still alive in America.

Good Neighbors

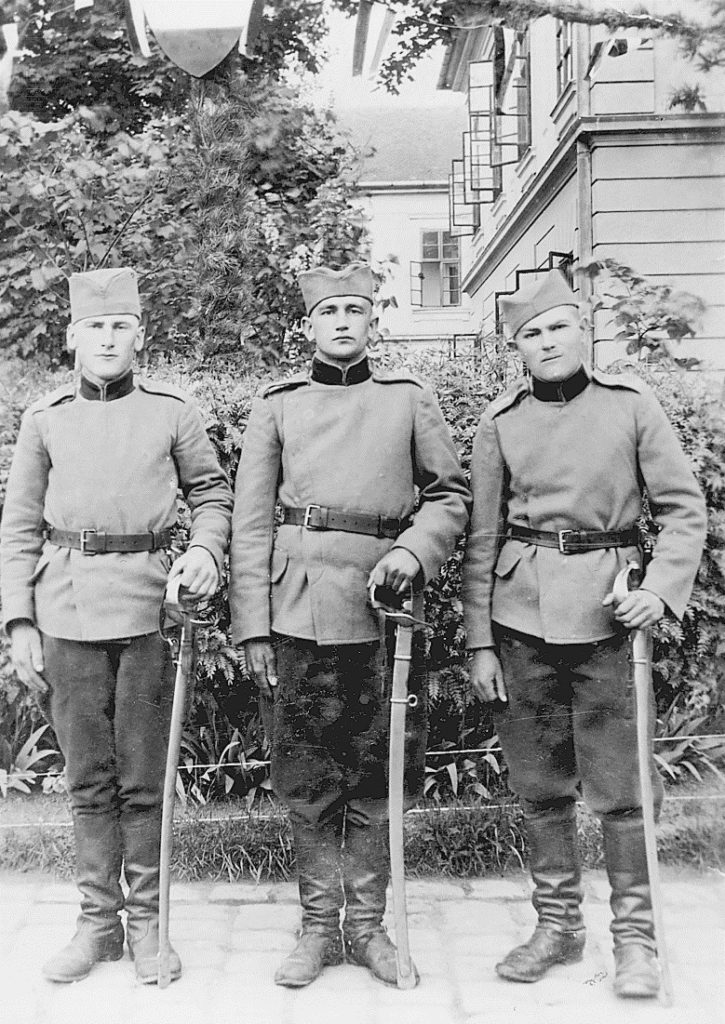

Perhaps the material realities of a multi-ethnic empire persuaded the Donauschwaben not to be anti-semitic, or perhaps they took the fundamental lessons of Christianity more seriously, but over 250 years of peaceful co-existence among Serbs, Croats, Muslims, and Jews, to name but a few, is eloquent enough evidence of the truth. Until the arrival of Hitler and Stalin, the Donauschwaben were considered “good neighbors.”

To learn more about the German community in Chicago, click here.