Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is one of the best-known pieces of American literature. But the story is not just a work of imagination. It is rooted in the landscapes and lore of New York’s Hudson Valley, a region whose atmosphere of mystery helped inspire Irving’s legend.

And wouldn’t you know: Aaron Burr may have played a key role!

Call Me Ichabod

There lived an actual man named Ichabod Crane. An officer during the War of 1812, Major Ichabod Crane’s campaign adventures in Sackets Harbor, New York, though noteworthy, were not exceptionally heroic.

His exploits interested Washington Irving enough for a meeting after the war. It provided the author with an onomatopoeia description for a bird-beaked scarecrow of a schoolmaster. Lockie Longlegs alliterates, lopes and looks good on paper, but the name Ichabod Crane sang out for a Yankee pedagogue.

Later, some sources say the real war bird objected vigorously to this appropriation of his moniker. He felt tainted by association with the snipenosed teacher.

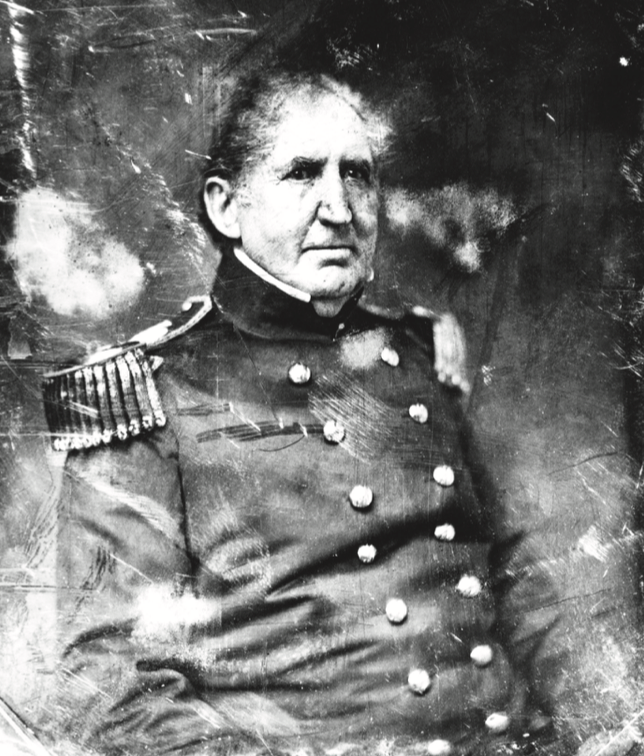

One look at the daguerreotype of an elderly Colonel Crane, pictured above, shows a resemblance in name only. Irving’s Ichabod shaped the archetypical, charmingly clueless nerd we love to frighten. He is the geek who goes on to get some revenge on the bullies either as a lawyer or a Sleepy Hollow ghost. And we all know how much Americans love ghosts!

Headless Horsemen

Irving avidly collected stories of the American Revolution. Later, living in an amazing Hudson Valley home, he wrote an extensive biography of his namesake, George Washington. One source of Irving’s tales sprang forth from Aaron Burr. The Irving family always maintained friendship with the disgraced former vice president. Indeed, in 1825, Washington Irving even wrote a sympathetic story about the Little Man in Black who is unfairly branded a witch. His readers knew the darkened man was Burr.

Aaron Burr served as aide-de-camp to the “Old Wolf,” General Israel Putnam, who fought with Heath and Washington at the Battle of White Plains. One of Putnam’s militiamen from what is now Rockland County suffered a terrible fate. Abraham Onderdonk, according to a neighbor quoted in a Hackensack, New Jersey newspaper, “was killed by a cannon ball from the enemy separating his head from his shoulders.”

Surely this is the kind of incident Burr would share with a wide-eyed Washington Irving around long-stemmed pipes and brandy. Distinguished Irving biographer Andrew Burstein concurs. “It is not unreasonable to consider that Irving might have known the details” of this tale.

Other scholars say Irving converted the headless patriotic American into a reviled Hessian for a more dramatic effect. Why base The Legend on a true tale gleaned from the Little Man in Black, when it is more reasonable to accept that Washington Irving read about the Hessian’s decapitation in General Heath’s 1798 published memoir? Stories of headless soldiers floated in the gloomy Sleepy Hollow air when Irving first passed through in the 1790s. A documented account of a Hessian made headless on Halloween 1776 is the core of the kernel of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

Add Jesse Merwin’s charivari, scores of local curses, spells and ghost stories, and Washington Irving certainly has enough material for his 1818 epiphany crossing London Bridge. Another rich source, however, for the lore of the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow needs some exploration.