On August 6, 1945, an American bomber dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. But that world-changing moment would never have happened without an explosion that occurred a few weeks earlier.

At 5:29 a.m. on July 16, the Trinity Test explosion of the first atomic bomb changed the world forever. It was the first blast in what is now known as White Sands Missile Range, and it marked the beginning of the end of World War II. In southern New Mexico, although the Manhattan Project was still top secret, everyday people witnessed the test, experienced its light and power, felt the earth move, and knew the world had changed. Here are some of their stories.

Americans see the preparation

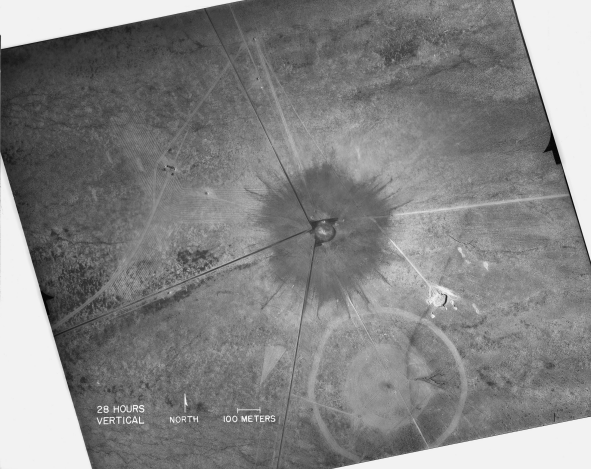

bomb explosion at the Trinity Site. Photo by Elva K. Österreich, 2019.

Clara Snow’s reaction was “stunning, emotional, a combination of fear, anger and bitterness that led her to tears.” “It was as if the air had died,” Snow told Tularosa Basin historian David Townsend, who interviewed many locals in the 1970s.

Most of Townsend’s sources did not notice much unusual activity prior to July 16, 1945. The people of Carrizozo, a railroad town, were used to heavy movement of men and equipment as the war still raged in the Pacific.

Some who were interviewed were convinced there was unusually heavy truck traffic at the time. Snow told Townsend that the government was moving a huge amount of garden hose somewhere. Union Pacific men had heard about some unusual equipment being moved on the Santa Fe through Socorro. Townsend wrote that official records reflect a frenzy of activity from July 12 to July 16, “but mostly in the Stallion Range area, across the Basin from Carrizozo.”

One of the interviewed witnesses had to go to the Trinity Site to move some equipment and knew “something was up” because of the tense atmosphere. “He saw a tower with what looked like a ‘little black pot hanging out on an arm of it,’” Townsend wrote. “When he asked about it, he was told simply that it would not be there when he came back.”

Americans see the explosion

Since the bomb went off at 5:25:45 a.m., the sources who remember the experience were “early risers, readying for work, cooking breakfast, or had been up all night nursing a sick child.” Townsend continued:

“They remember the light above all else, above the noise, above the tremors, above everything. One minute it was dark; then it was bright as day. The light faded gradually into what seemed a deeper darkness. Then the sound, not much noisier than distant thunder, and the tremor that rattled windows and dishes. The first thoughts were religious: the end of the world; the next, practical and reflective of wartime thoughts: they have sabotaged the train, or blown up the base, or.…Those who went outside to see what had happened were treated—or condemned—to a view never seen before by man. A giant column of smoke with light gradually dying down its stem was visible in the re-gathering darkness. As this false dawn was dying in the west, the true dawn was giving a hint of a purer light from the east. That picture stuck in the minds of the witnesses, indelibly imprinted. Then the silence came—an eerie silence where it seemed the air had died.”

Another interviewer, Howard Tate, spoke to a man who was in a remote location at the time, closer to the Trinity Site than to Carrizozo. The man said he was lying in bed under a sheet in a room with windows open. The curtains were moving gently in the breeze. Suddenly, it was daylight, and the sheet and curtain were blown in one direction. Then it was dark, and the sheet and curtains were sucked back in the other direction. Townsend said that sucking behavior may explain the silence reported by other witnesses.

Americans deal with the fallout

Österreich, 2019.

Flora Millfelt saw the Trinity test explosion from the banks of the Rio Grande. Her family owned a ranch along the river near San Antonio, New Mexico, and while most people in the area were not told about the Trinity test, her father had been instructed to move some of his animals away from their grazing areas, so he took his family out to watch.

“We went and watched it,” Millfelt said, “my mother and all of us kids along the river. And it was five o’clock in the morning, and it was supposed to be dark, but it was just brighter than daylight. It looked like it was a ball of cotton coming up, you know. It was red. We were about a half a mile away. There were fourteen of us kids. Father knew about the bomb because they told him to move his cattle and sheep and goats. We got along the river; my dad got the information. We knew exactly where to go to watch. And we just saw this red cloud comes up, then it turns orange then it turns yellow then a boom, and it was brown and clear up in the air and everything was just as light as day.”

The bombing may have had dangerous consequences for locals like Millfelt. “We weren’t watching for radiation or anything like that,” she said, “we didn’t know about that. We had six doctors that were partners with us in 2002. I came up with breast cancer and was talking to him about it. He says 99 percent of my patients of people with breast cancer [at his Albuquerque practice] were people that were there when the atomic bomb went off. Most of my family died of some kind of cancer.”

The Manhattan Project Trinity Test: Witnessing the Bomb in New Mexico

By Elva K. Österreich

At 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, the Trinity Test explosion of the first atomic bomb changed the world forever. The dropping of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan followed soon after, but it was the first blast in what is now known as White Sands Missile Range that marked the beginning of the end of World War II. In southern New Mexico, although the Manhattan Project was still top secret, everyday people witnessed the test, experienced its light and power, felt the earth move and knew the world had changed. Author Elva K. Österreich shares the stories of their experience and how their lives were transformed.