As the nation deals with questions pertaining to climate change and energy independence, coal remains in the headlines. The coal industry in the United States has a long history, intertwined with the rise of the industrial economy and the emergence of labor unions.

Pre-industrial Use of Coal

People have been using coal for thousands of years. Coal heated the homes of ancient Romans. The Hopi Indians in the American Southwest started using the fuel in the early 1300s for baking pottery, cooking food, and heating homes.

English settlers discovered coal in Eastern North America in 1673, but commercial coal mining did not begin until the 1740s. It remained a small industry until the early 1800s, as American settlers preferred to use the plentiful supplies of wood.

The Rise of Coal

The American coal industry began in Virginia, with the exploitation of the coal of the Richmond Basin. Early economic nationalists, including Alexander Hamilton, thought coal could help drive national growth and development. Because of slavery, colliers, or coal miners as we now call them, had access to cheap labor to exploit the coalfields, but the demands of the plantation system and the poor transportation network limited its potential.

Meanwhile in Pennsylvania, miners began extracting a higher carbon form of coal, known as anthracite, on an industrial scale. It rapidly became a common source of residential heating in Philadelphia and other northeastern cities, and by the 1840s, anthracite became the standard form of coal used throughout the Eastern seaboard.

Through the middle of the 19th Century, the coal industry expanded and spread. Ohio produced over a million tons of coal by 1853, and by 1861 coal mining had expanded to 20 states.

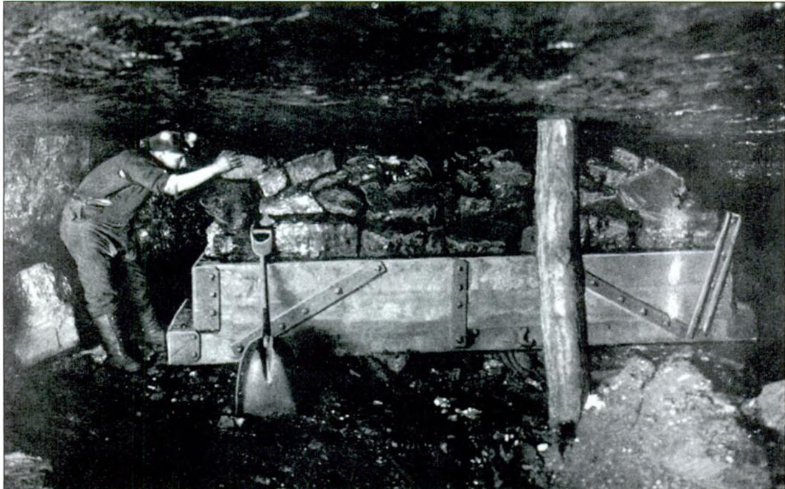

At the time, coal mining operations remained small businesses. A skilled miner could employ a few laborers to extract coal close to the surface. Many coal seams were exposed on hillsides or river banks, and those rivers allowed coal barges easy access to the mines.

Labor relations and coal mining did not become contentious until much later. Surface mining meant minimal danger to laborers. In addition, because the mines were small, workers and management worked alongside each other. Several attempts to organize mine workers took place in the 1840s and 1850s but generally had little lasting influence.

Coal Before the Civil War

In 1840 people began using anthracite coal to make iron. This advance increased the efficiency of the iron furnaces, as well as improved the quality of the iron. By 1860, anthracite produced 56% of American pig iron.

Production levels remained high through the years leading up to the Civil War, even though prices fell. By 1860, over 20 million tons of anthracite came out of American coal mines.

The Civil War and the End of the 19th Century

The Civil War affected many aspects of the national economy, and coal was no exception. The war increased prices by nearly 50%. The demands of the Union military led to more coalfields opening, including new bituminous coal mines in Maryland, Ohio, and Illinois. Railroads expanded to reach these new mines and became an integral part of the coal trade.

Railroads also began purchasing coalfields directly and leasing them to mining companies. The railroads opened the coalfields of West Virginia by connecting them with industrial outlets. The coast-to-coast railroad built immediately following the Civil War provided access to coalfields west of the Mississippi River.

New technology drove the evolution of the industry. Extraction of coal went underground, requiring pumps and new machinery to obtain the coal. The industry also developed methods to clear bituminous coal of its impurities by producing coke, a fuel with few impurities and a high carbon content, crucial to making iron and steel.

The increase in coalfields meant national production reached 80 million tons by 1880. Prices for coal, however, remained relatively low, and the industry fluctuated with boom and bust periods.

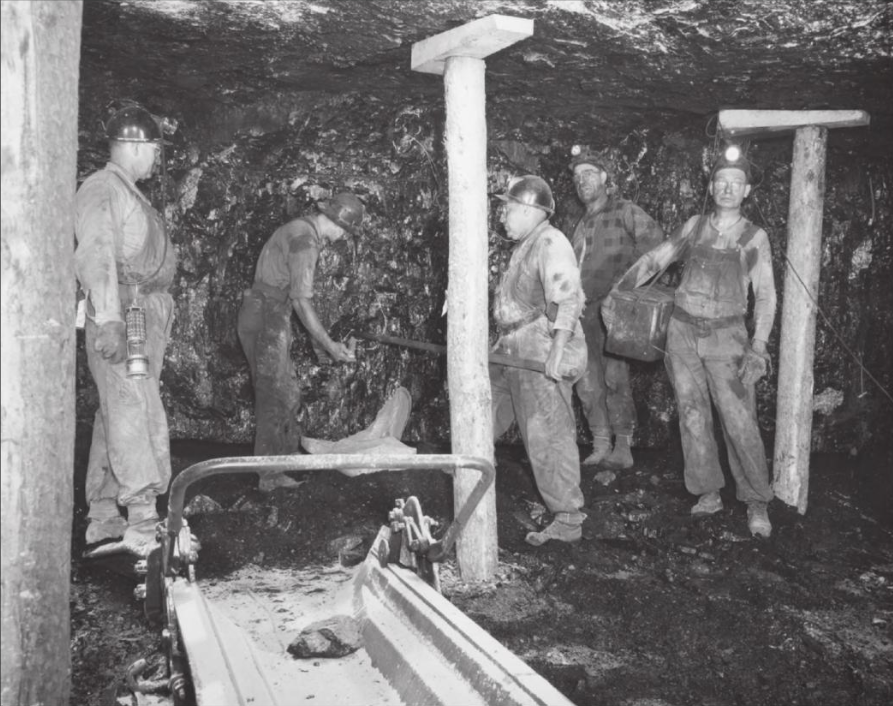

Labor unions began forming as mining became more capital-intensive. It remained industry standard to pay miners by the ton rather than the hour, continuing the model begun before the Civil War. After initial false starts, including the rise of the Molly Maguires secret society, the United Mine Workers firmly established itself and had over 250,000 members by 1903.

State of the Coal Mining Industry Today

Contentious labor relations continued into the 1900s, even as the industry grew. Soon, however, the oil boom began in earnest; primarily due to refinement improvements and the expanded use by the public of the automobile as a primary means of transportation. Technology helped make hydroelectric power more efficient. By the mid-20th century, oil and natural gas began to overtake coal as the leading fuel source for energy production

The coal industry reached peak employment in 1924, with over 860,000 miners employed. That number fell consistently until the late 1960s — though with several slight upticks around World War II.

Despite a slight rise in mine employment in the 1970s in response to the energy crisis of 1973, the coal industry, as of September 2016, employs just over 75,000 mineworkers. Most of the mining jobs disappeared as a result of technological advances: machines can extract coal more efficiently than a human can.

Competition from natural gas, solar, wind, and other sources also bedevil the industry. As solar and wind power become both more efficient and prevalent, the need for coal-fired power plants will decrease even further.