Napa Valley is known for its wine and winemakers, but just beneath the fertile soil lies another, more complex version of its history. That history stretches from African American farmers to female brothel owners. But one of the most surprising and heartbreaking stories involves the forgotten history of the first Napa Valley Chinatowns, which were once home to thousands of immigrants. These towns thrived – until they were undercut by outsiders, which led to shrinking populations and razed buildings.

New beginnings

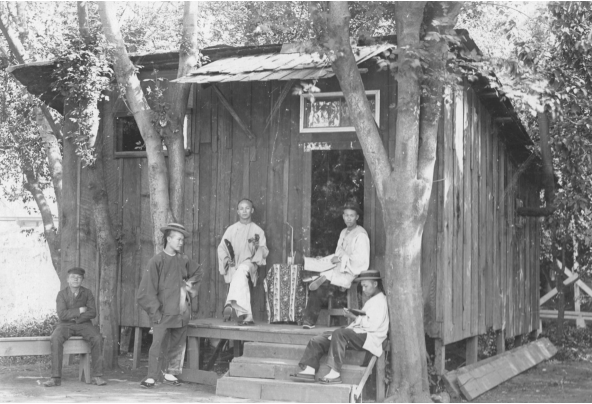

Thanks to the jobs that came from building the railroads and also working at the vineyards, Chinese immigrants formed permanent settlements in nearly every community in Napa County. Work gangs passing through the area for contract jobs at farms, mines and vineyards lived in boardinghouses and temporary encampments, but families and entrepreneurs also established residential and business districts. They formed Chinatowns to maintain their cultural traditions, protect themselves from hostile Americans and because, in many cases, they were the only places where they were allowed to live.

Not long after the first Chinese immigrants arrived in the valley in the early 1850s, the county’s first Chinatown was established in Napa. It was built on a small spit of land bordered by the Napa River, Napa Creek, Soscol Avenue and First Street. Anywhere from three hundred to two thousand residents occupied several businesses, private homes, boardinghouses, gambling houses, opium dens, brothels, two commercial gardens and at least one Chinese restaurant.

George Cornwell, landowner and developer of the neighborhood, was Napa’s first postmaster; therefore, Napa’s first post office was erected in Chinatown. It also boasted a Taoist temple, the Temple of the Northern Realm, built in 1886 in part by Chan Wah Jack. Inside was an altar brought from the old country by Wah Jack in 1860. During Chinese New Year, the temples were filled with offerings of rice, meats, fruits, coconuts, candies and Chinese delicacies. The second floor of a gambling hall held another small temple.

Life in Napa’s Chinatowns

Residents of Napa Valley Chinatowns made the best of their limited circumstances. A few operated mercantile and grocery stores specializing in Chinese goods and foods. Store owners also often doubled as employment agents or onsite crew bosses. The agent or crew boss distributed wages to workers, settled disputes and organized work schedules, among many other responsibilities.

In St. Helena in the 1880s, Ung Ching Wah ran a store that offered both workers and a boardinghouse for them to live in. Yung Him ran a triple-threat store in Rutherford in the 1880s that offered groceries, employment and laundry services. In Napa in the 1890s and 1900s, Bing Kee operated an employment office out of his store where he also sold goods from China and Japan, women’s underwear, items made of bamboo and fireworks.

Competition was fierce between employment agents, and conflicts occasionally turned violent. One fight erupted in June 1890 between Sam Lee of Calistoga and Quong Wing of St. Helena; both had secured contracts for their laborers to chop wood for Charles Edward Loeber. Lee and Wing exchanged words in a store in the St. Helena Chinatown, then shots were fired. Two men were charged with attempted murder, a third was charged as an accessory for instigating the attack and a fourth went on the lam.

An unjust future

Although Napa County once contained many Chinese settlements, none remain. The St. Helena Chinatown was partially destroyed in 1884 by a fire believed to have been caused by a lamp in Quong Loong High’s store. The neighborhood was quickly rebuilt, but two years later, John and Mary Gillam sold the land out from under its residents after concerns that someone might try to burn it down again.

The Chinese residents published a letter in a local paper reminding anti-Chinese agitators that they had legal leases but offered to leave if compensated fairly. A representative from the Six Companies tried to buy the land for more than it was worth, but it was instead sold to members of St. Helena’s Anti-Chinese League.

The new owners jacked up the rent, so the residents took them to court. The Chinese stayed and paid no rent during the several years of legal maneuvering. An out-of-control cooking fire wiped out half of Chinatown in 1898. Another blaze in 1911 caused by a spark from a backyard fire destroyed what little was left of St. Helena’s Chinatown.

The plans for razing the last of the Napa Valley Chinatowns were first announced in 1920, when the H. Shwarz Company selected the site to build some new warehouses. No progress was made, and the matter was dropped. A decade later, the city opted to move Chinatown to a new site so as to beautify the neighborhood by turning it into a yacht club. By that point, only seventeen people lived in Chinatown, ten of whom were members of the Chan family.

Over the intervening years, many priceless personal items were stolen, and the Chans eventually packed up and left town. The yacht club was never built. Much of the old Chinatown site washed away in the 1986 flood, and what little remained was lost in the flood control project of the early 2000s. All that is left is a plaque on the First Street Bridge.

Hidden History of Napa Valley

by Alexandria Brown

Napa Valley is known for its wine and winemakers, but just beneath the fertile soil lies another, more complex version of its history. Uncover the story of Napa’s first Chinatown—once home to nearly five hundred immigrants—that dwindled to fewer than seventeen residents before the last buildings were razed in the early twentieth century. Meet the small but determined group of African American farmers and barbers who called Napa home and the indomitable May Howard, a successful businesswoman and brothel owner. Learn about the Bracero Program that kept many of Napa’s wineries, including Krug, Beaulieu and Stag’s Leap, thriving during World War II. Join author Alexandria Brown as she explores these lesser-known stories of the ordinary people who helped shape modern-day wine country.