This summer’s political conventions were already facing uncertainty, due to the coronavirus. Now the nationwide protests against police brutality are adding another complicating factor. But there’s a history with this factor—the protests that haunted the Democratic convention of 1968.

If 2020 has felt overwhelming, 1968 was arguably worse. That year was the single bloodiest for the American soldiers mired in Vietnam. Anti-war protests were cropping up in dozens of cities around the country.

Then, beginning in April, the nation witnessed the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. Protests and riots intensified and spread. In Chicago, a city with a proud African American tradition, thousands took to the streets after King’s death; eleven of them died.

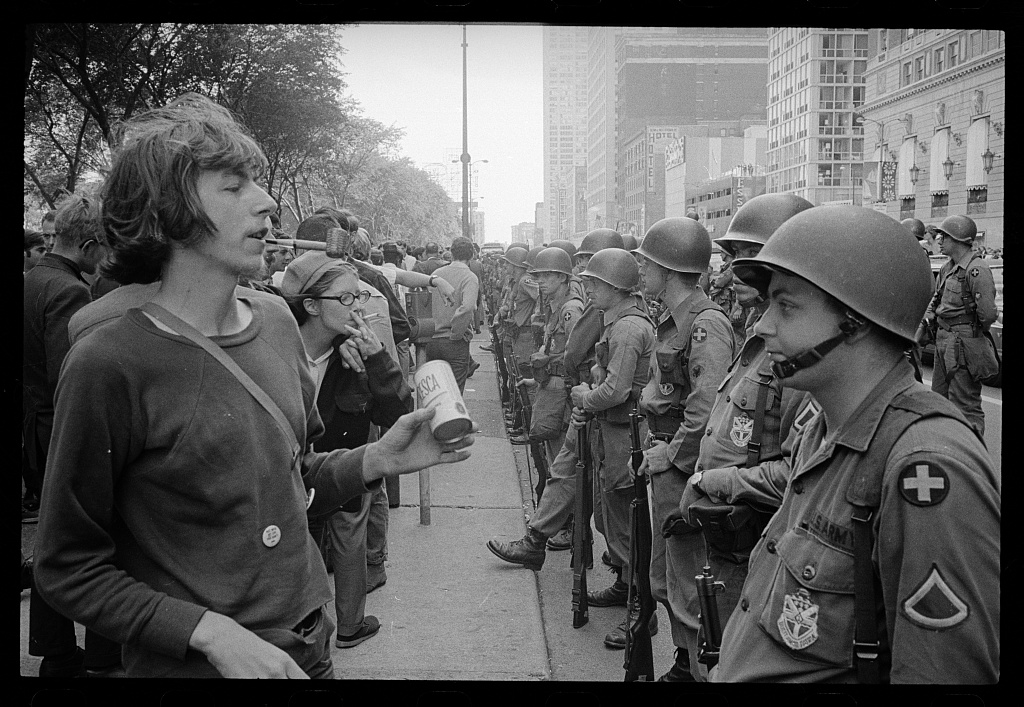

Later that summer, the Democratic party gathered in Chicago for its convention. Lyndon Johnson had already declined to seek reelection, and with Kennedy dead, a number of candidates were appealing to delegates: Hubert Humphrey, Eugene McCarthy, and George McGovern, among others. Chicago’s mayor, Richard Daley, put more than twenty thousand police officers and National Guard members on the streets in the hopes of stopping any protest. The convention’s site, the city’s International Amphitheater, was wrapped in barbed wire.

During the convention, there were numerous riots. The response was quick and brutal, marked by tear gas and beatings. The so-called Walker Report, an independent analysis of what had happened, found “unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence. . . . That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat.”

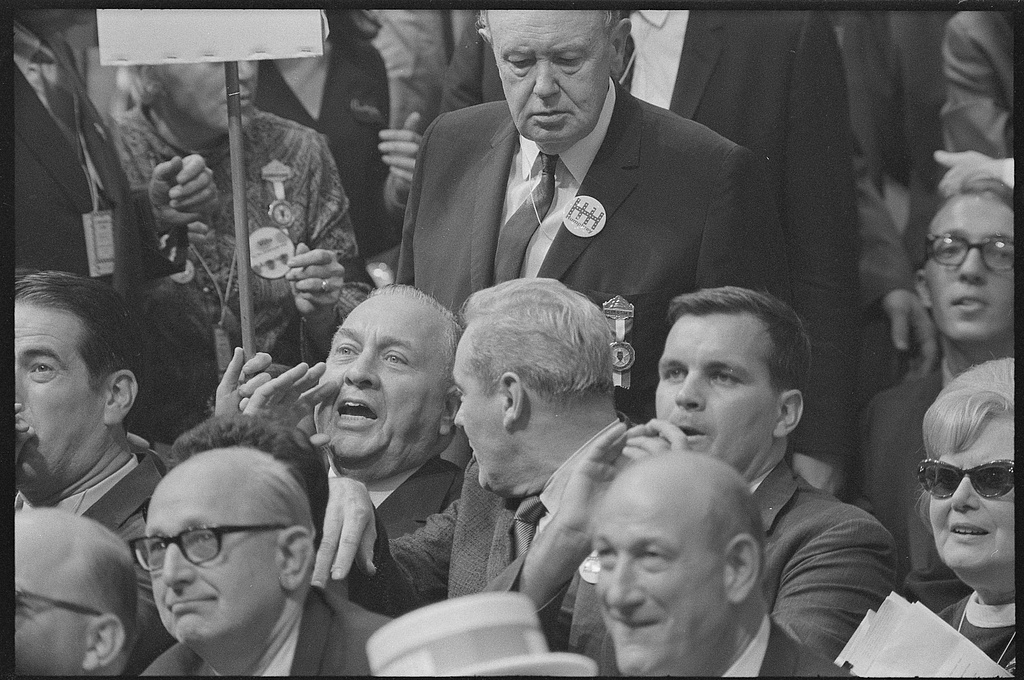

All of that may sound familiar, but there’s at least one difference between 1968 and 2020. In 1968, there was plenty of political drama, with the delegates eventually settling on Humphrey. Norman Mailer, who was covering things from the floor, wrote about the “hecklers, fixers, flunkies, and musclemen,” whose machinations added up to “the wildest Democratic convention in decades.”

In 2020, though, both political parties seem to have settled on their nominees. This is a good thing, in terms of convention commotion, since those parties will need to figure out how to stage their big events in a time of protests and pandemic.

That backdrop—along with thinking about a policy response that will address the issues raised by the current protesters—seems like more than enough to deal with. It might even be more than America had to worry about in 1968. As the Princeton historian Julian Zelizer has written, “Today’s situation is even worse.”

READ MORE: Civil Rights & Social Justice History