Before the Beginning

Jean Baptiste Point DuSable was one of the many African Americans who lived in this area before the First Great Migration, which occurred largely between 1915 and 1925. Who knows how many escaped slaves, free men and women, and undocumented peoples lived in the Chicago area before formal numbers were assembled? From DuSable’s time to the 1830s, there had to have been African Americans who somehow survived and thrived in the area. The Encyclopedia of Chicago says the population rose from 4,000 in 1870 to 15,000 in 1890, and then subsequently to 40,000 by 1910. Though some scholars say the Great Migration began then, many give credit for the real onslaught to the Chicago Defender’s Great Northern Drive, which did not start until May 15, 1917, as America entered World War I.

Read More: African Americans in Chicago by Lowell Thompson

Goin’ to Chicago

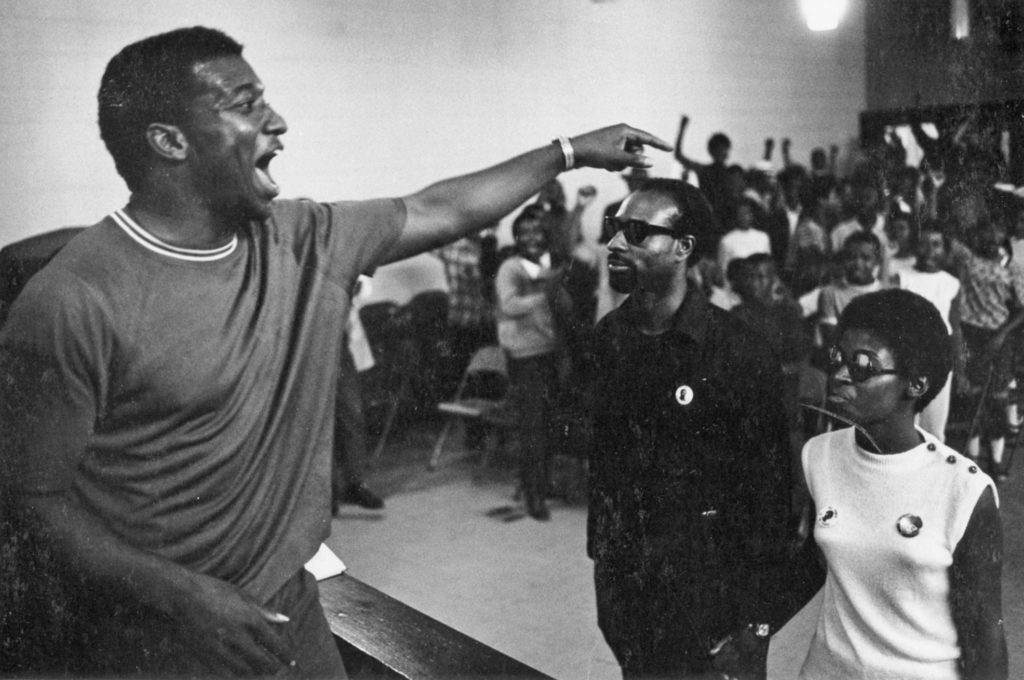

Experts vary on exactly when the Great Migration actually began (between 1910 to 1915). It marked a period of great growth in the African American population of Chicago. One big event between these dates was the World’s Columbian Exposition, a world’s fair in 1893 that took place on Chicago’s South Side. Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells had come to agitate for African American participation and were met with the usual obstructions. But it was Robert S. Abbott and his sensational Chicago Defender who gets credit (or blame) for getting most black refugees from the South to Chicago. In 1925, Chicagoan Milton Webster teamed up with New Yorker Asa Phillip Randolph to start the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). Many believe this helped lead to the leadership talent and tactics that would a few decades later spark the civil rights movement. E.D. Nixon, the man who brought a young minister named Martin Luther King Jr. to Montgomery, Alabama, led the 1955 bus boycott and was the head of both the BSCP and local NAACP.

Read More: African Americans in Chicago by Lowell Thompson

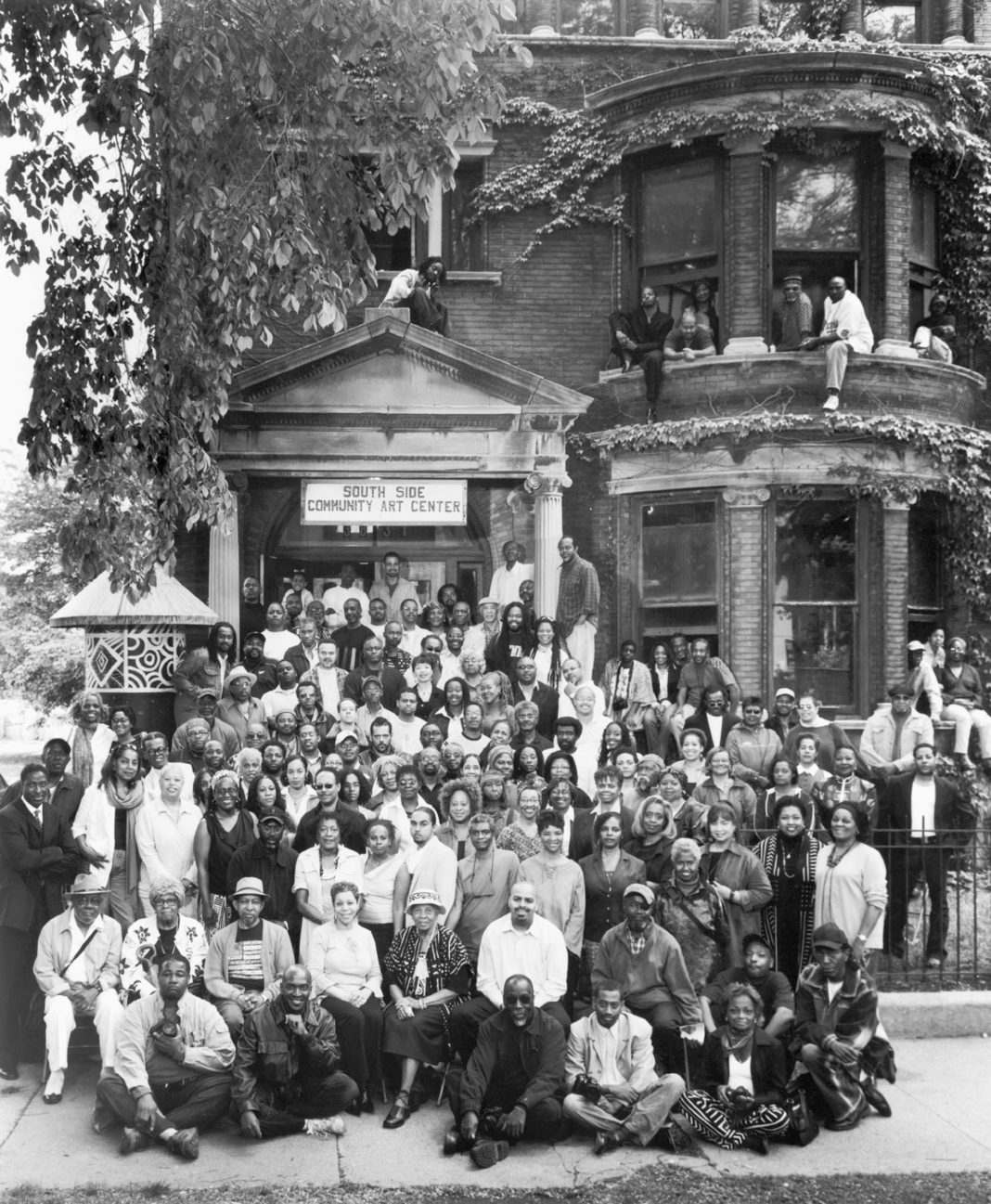

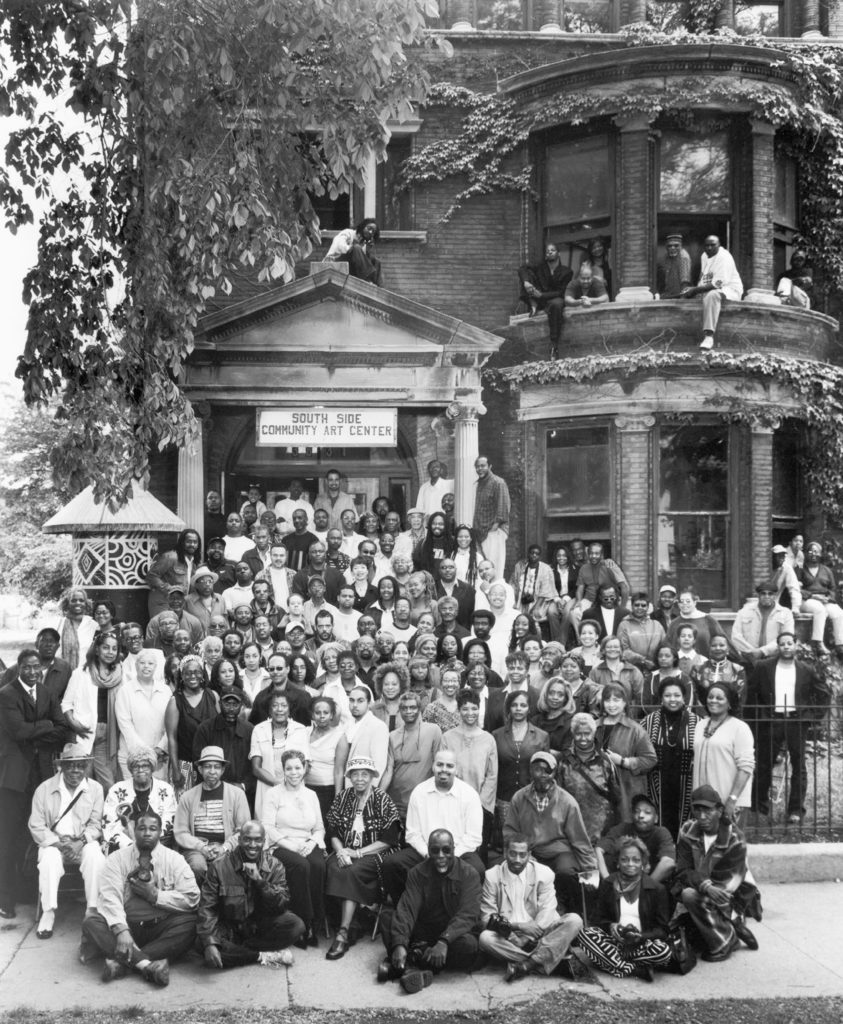

The South Side of Chicago was considered by many experts to be the black capital of America. From 1940 to 1960, sociologists say the African American population in the city grew from about 278,000 to over 800,000. By then, it comprised a larger portion of the city’s total and was more politically and culturally monolithic. But the new migrants faced a much less welcoming city. By the mid-1970s, America’s postwar economic boom was just about done. Even under-educated white Americans were beginning to lose their relatively high-paying, blue-collar jobs to international competition. Typically last hired, many first-fired African Americans would now not be hired in the first place.

The White Flight

By the late 1940s, the growing African American population had stretched the proverbial Black Belt all the way to the South Boulevard to Sixty-third Street. New migrants had fled the South after losing much of their work to new cotton-picking machines and were flowing into Chicago’s Illinois Central Twelfth Street station. Those numbers dwarfed those of the first migration. They were taking over areas like Lawndale on the west side as Jews and Italians moved out to the newly built suburbs. This was sponsored by the discriminatory lending policies of the Federal Housing Administration and the US government.

Buy the Book: African Americans in Chicago by Lowell Thompson

The Last Word?

The American tradition of the demonization and marginalization of African Americans is alive and well in the second decade of the third millennium in Chi-Town. The latest newspaper headlines chronicle the crimes of a relative handful while ignoring the continuation of historically unequal policing policies, labor discrimination, and pitiful education system that turns citizens disproportionately into criminals or wards of the state. With all the problems that black Chicago had, what is most amazing is how so many of them achieved so much in spite of it. But hardly any acknowledge the almost unbelievable accomplishments and people that have come out of and still live in Chicago.

To learn more about the African American community in Chicago, click here.