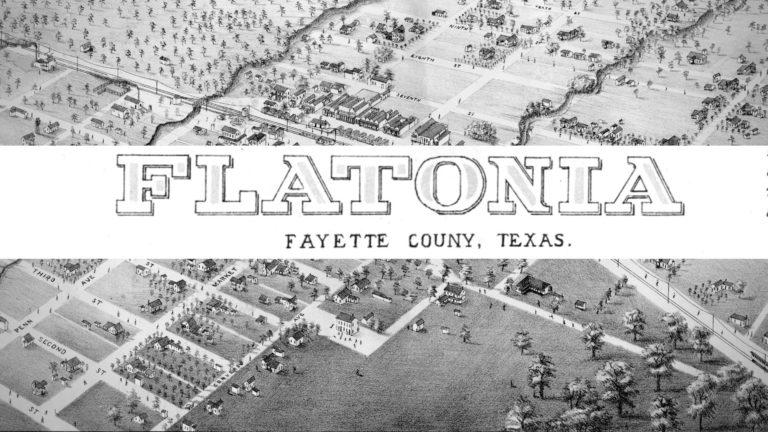

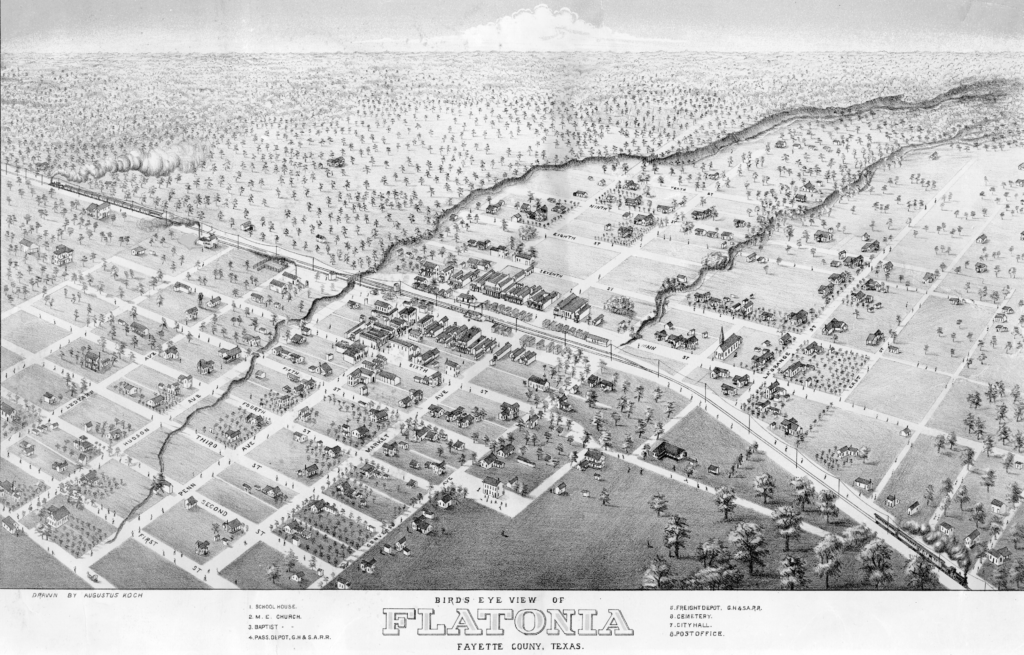

Part of the charm of Texas is her small, frontier towns. Why, do you suppose, so many westerns are set in Texas? Flatonia, Texas fits the bill perfectly. As Texas dramatically won independence from a neglectful Mexico in 1836, Anglo settlements exploded along trading routes and rivers. In addition, central Texas found itself an ideal location for growing cotton. Following the Civil War, small communities competed to have major roads and rail pass through them. German and Czech immigrants who settled in Fayette County, and led by the new town’s namesake F.W. Flato, leaned into the future.

Cotton

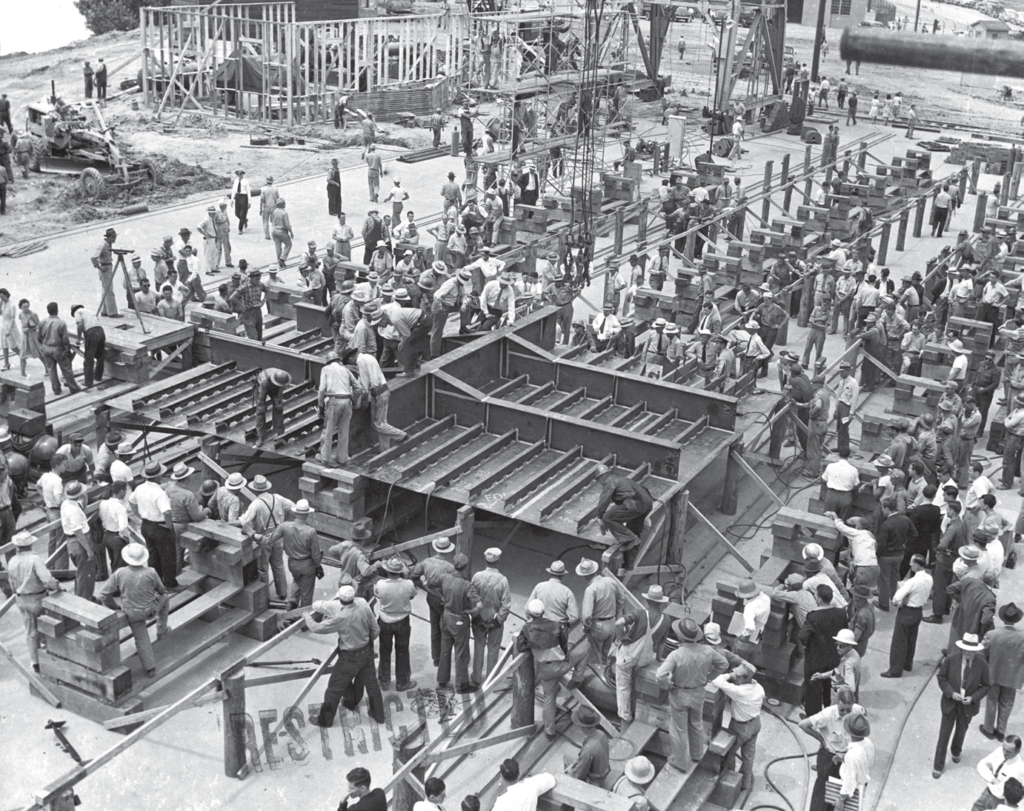

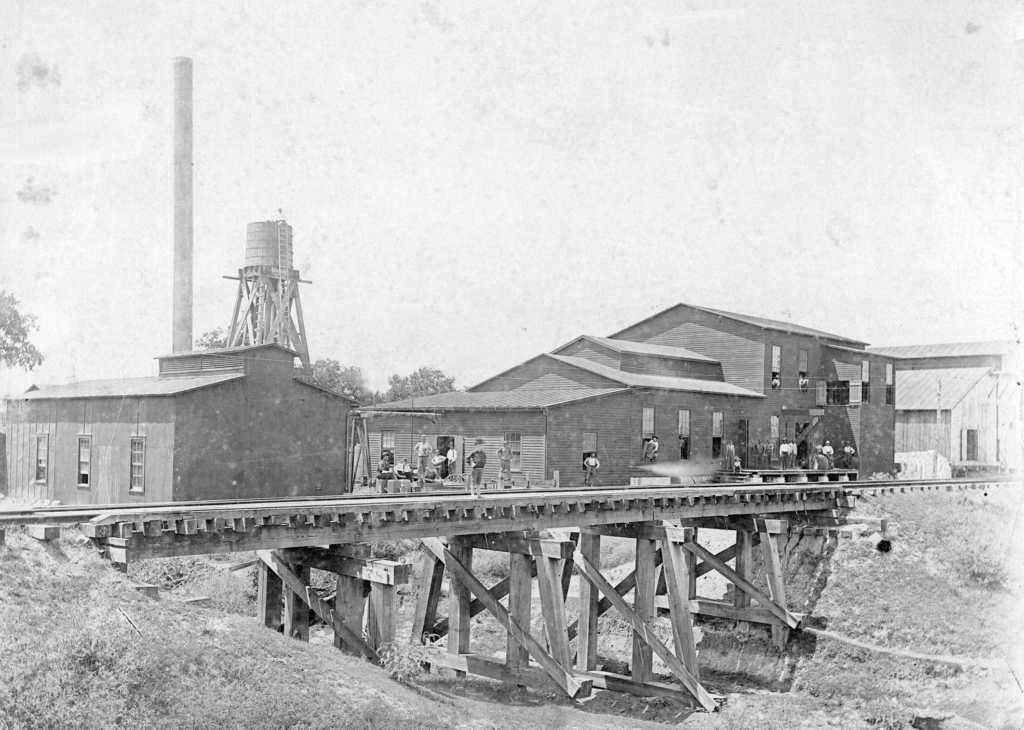

In fertile land between the Brazos and Colorado Rivers, new European settlers found success growing cotton. But getting cotton and produce to mills and markets was nearly impossible on Texas’s network of muddy roads. Businessmen found a solution for the young state: rail.

Rail

In 1874, so excited for the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway to be building its line nearby, Flatonia moved itself the 2 miles just to be in its path. That shrewd decision allowed for local farmers to get their crop to market in Houston and Galveston. Both freight and passenger depots served the growing Flatonia; and, by 1887, a new north-south railway intersected the existing east-west one.

Commerce

Seeking to take advantage of the 2 railways that intersected in Flatonia, business leaders encouraged industry to relocate to the bustling Texas town. Flatonia became the central shipping point for neighboring Lavaca and Gonzales Counties and the quiet county seat La Grange. Mills, factories, hotels, churches, schools, and banks ensured Flatonia would thrive as a local industrial hub well into the 20th century. In the 1930s, the Chamber of Commerce successfully lobbied to have the new US Highway 90 pass straight through the business district.

Landmarks

While Flatonia’s fortunes waned as the 20th century progressed, the population has not changed much from the 1950s. Fortunately, several early Flatonia buildings still stand, providing the town with a charming historical feeling. These include the railroad crossing switch tower, the 1886 Arnim & Lane Building, the Central Texas Rail History Center, and the Lyric Theater. In the 1970s, Interstate 10, connecting San Antonio to Houston, bypassed historic Flatonia, so curious Texans must now make a point to find the old town when speeding down the highway.