This article was adapted from Crooked Politics in Northwest Indiana by Jerry Davich (History Press)

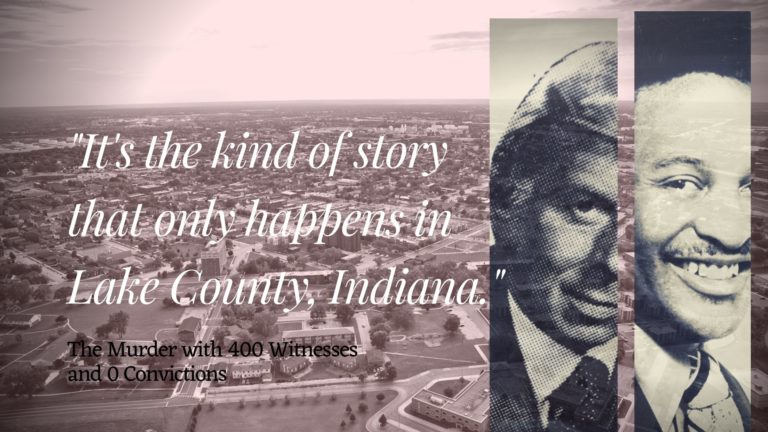

Only in East Chicago can a homicide take place at a political fundraiser with four hundred guests just a room away and nobody see or hear a thing.

Northwest Indiana during the twentieth century had a lot of jobs and growth. According to Calvin Bellamy, president of the Northwest Indiana Shared Ethics Advisory Commission, “Life was good and mostly free for the average citizen.” But the region also had political machines, powerful industrialists, and rampant corruption.

And that’s how this improbable scenario—fundraiser, four hundred people, witness-free murder—happened on May 15, 1981, inside the East Chicago Elks building at 4624 Magoun Avenue.

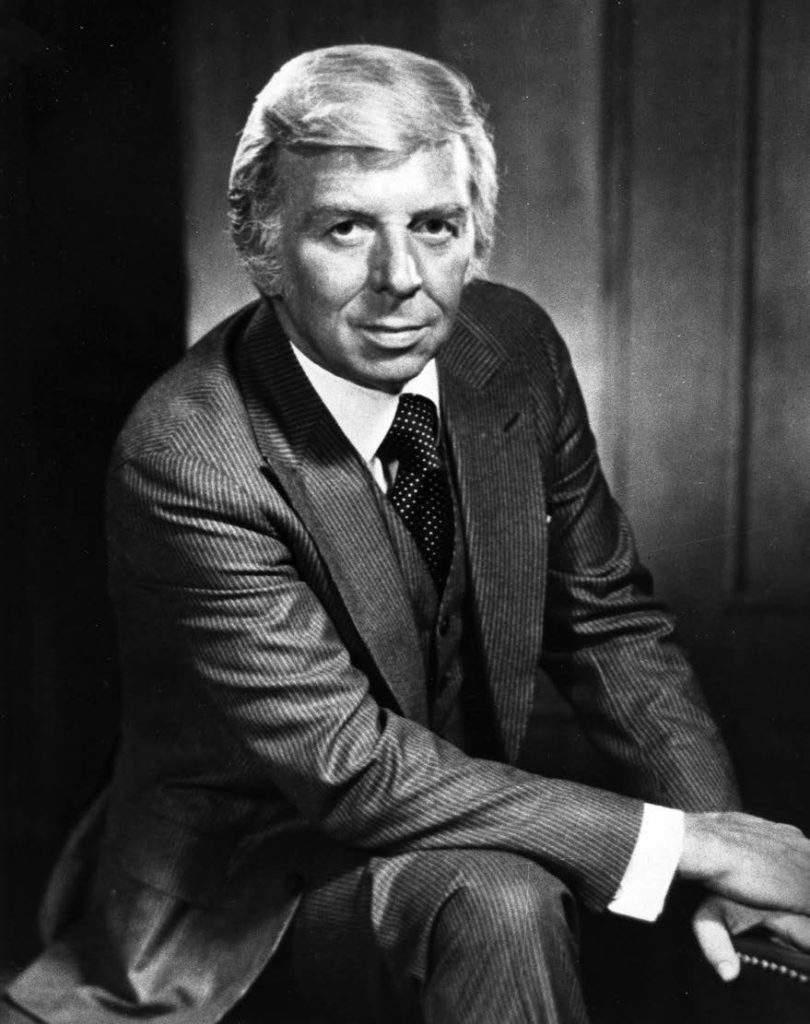

Jay Given, a fifty-one-year-old political power-broker who was once dubbed the city’s “midnight mayor,” was known to make or break politicians. He had a nasty temper and made enemies as fast as he made friends, former associates agreed.

From 1963 to 1973, Given served as city attorney and then later as an adviser for East Chicago mayor Robert Pastrick. It was rumored that the two powerful politicos had a falling out years later. In fact, on the very night of his murder, Given attended a fundraiser for N. Atterson Spann, Pastrick’s opponent for mayor at the time. Given may not have attended every political function in the city, but since his falling out with Pastrick, he wanted to realign himself with Spann.

On the night of the murder, Given won $300 in a ticket drawing at the Las Vegas–style fundraiser in the Elks’ ballroom. He had just left the room when, just after 11:00 p.m., he walked to the first-floor lobby toward the building’s main entrance. One witness claimed he saw Given and a man with dark hair, wearing a dark suit, get into a heated argument as Given left the vestibule. Given had his car keys in one hand and a cigarette lighter in the other, the witness said.

Police believe this was when the dark-haired man shot Given in the back of the head at point-blank range, execution style. According to the police report, the bullet went through the back of Given’s head, exited through the middle of his forehead, broke through a glass door leading outside and landed on the street, several feet away. The bullet’s casing landed on the vestibule floor, police said. Given’s body fell with his head lodged between the glass doors, the police report states.

At 11:14 p.m., an anonymous call came into police headquarters. A woman with a Spanish accent reported that a man had been shot. In hindsight, former East Chicago police chief Gus Flores, the primary investigator on the case, regrets that no one interviewed this female caller, who likely feared for her safety.

When the sound of the gunshot rattled through the ballroom, hundreds of guests made a mad dash out of the building. Some trampled over Given’s body, tampering with potential evidence, police said. No one came forward to admit witnessing the assassination-style shooting. At one point, a Jockey Club employee, Odessa Gamble, spent ten days in jail for contempt for not cooperating with police detectives.

One key clue, however, was discovered. A bullet casing found in the building’s vestibule turned out to be a match for a rare .45-caliber Detonics pistol. It was widely known around the city that East Chicago deputy police chief John Cardona owned such a handgun. No murder weapon was found and neither was Cardona’s rare pistol. The deputy police chief became the prime suspect in the case, but he was never charged.

To this day, Flores says the case still haunts him, offering a hint of hope that it can someday be solved. As one veteran attorney who worked that case put it, “It’s the kind of story that only happens in Lake County, Indiana.”