In Texas history, Rangers, ranchers, and cowboys stand a little taller than their frontier peers. Many have filled volumes with tales of their outsized personalities and bold heroism, and some Texas heroes like Sam Houston, Davy Crockett, Big Foot Wallace, and Charles Goodnight have become national heroes in their own right. But one such legend fell through the cracks of history — that is, until now!

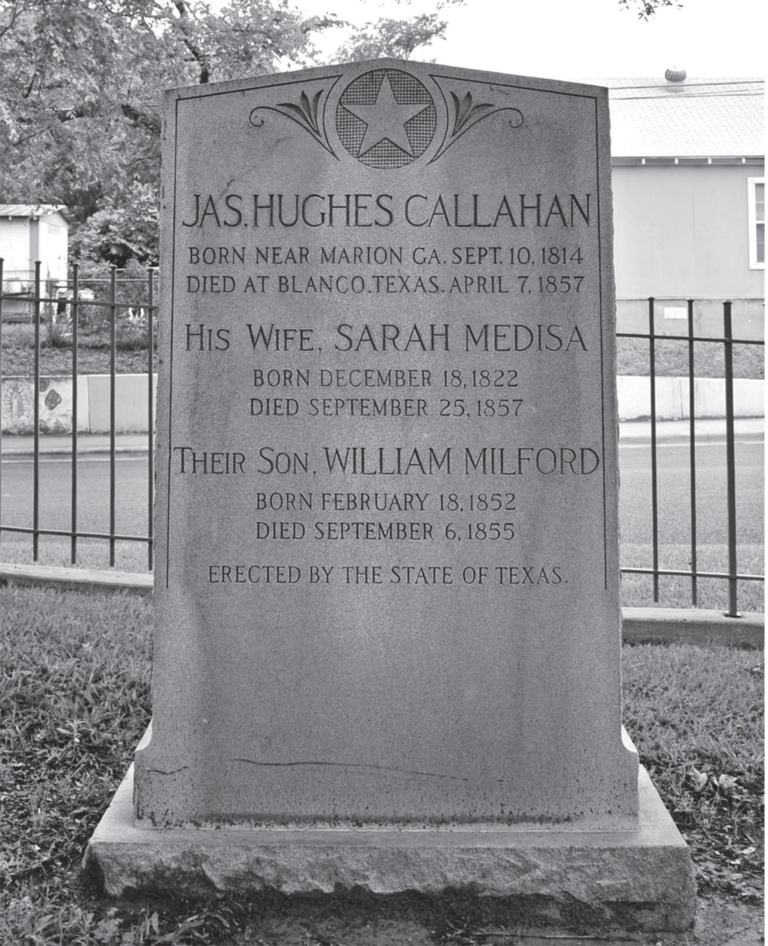

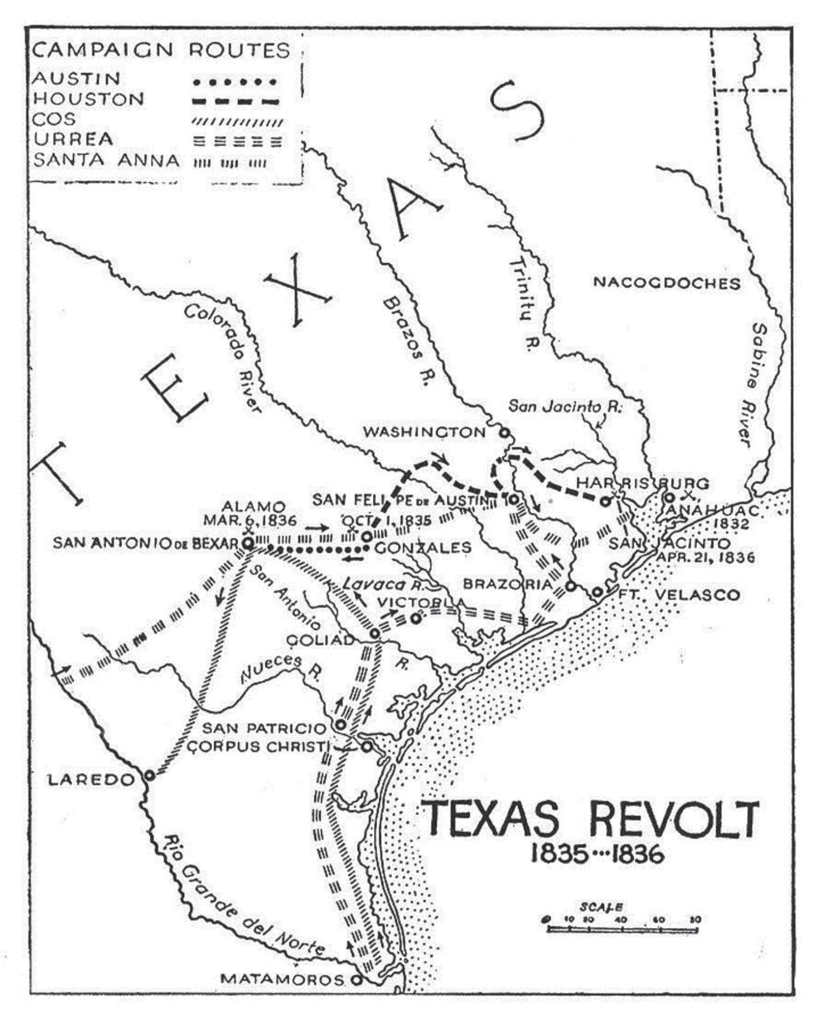

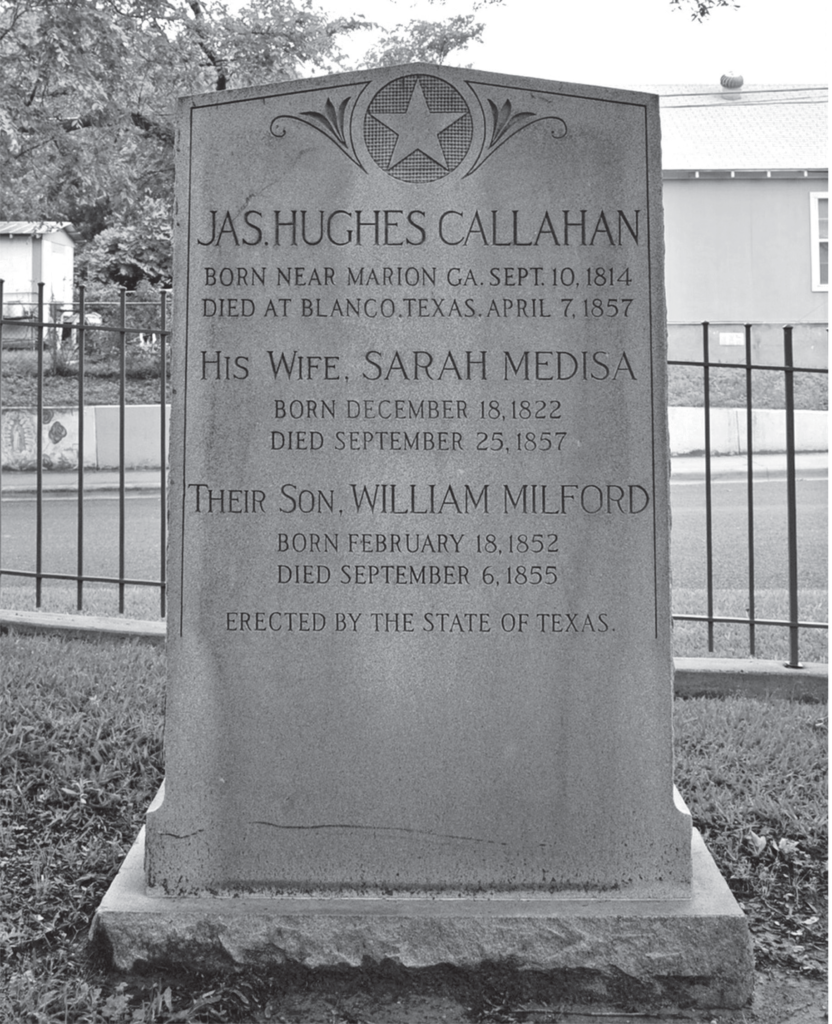

As a volunteer in the Texas Revolution, Georgia-native James Hughes Callahan came to Texas in 1835, and miraculously survived the Goliad Massacre. Later, Callahan served as a Texas Ranger, pursuing Indian raiders in central Texas, and twice engaged Mexican invaders. And in 1855, he led a Texas Ranger expedition to punish Lipan Apaches raiding from Mexico, but failed miserably, and barely returned — the boondoggle was later renamed The Callahan Expedition.

Gone To Texas

The Texas fever has treated us worse than the Cholera! Our office is completely swept Journeymen and apprentices, men and boys, devils and angels, are all gone to Texas. If our readers get an empty sheet or no sheet at all, don’t blame us.

Macon Telegraph, November 26, 1835

This so-called Texas Fever came from the romance of new land on the frontier, and an irresistible call to arms to topple a despot. Texas colonists, also called Texians, wanted to bring their Anglo traditions (including slavery) into the Mexican state. Being so far from the Mexican capital meant difficulty in governing the legal colonizers. But when Mexico insisted, the Texians rebelled and declared independence. Word spread fast into the United States, luring thousands to Texas to join the war. Odes have been written of the Tennessee Volunteers (both Davy Crockett and Sam Houston held political office in Tennessee and left the Vol State for Texas), but neighboring Georgia sent soldiers to Texas too.

The Goliad Massacre

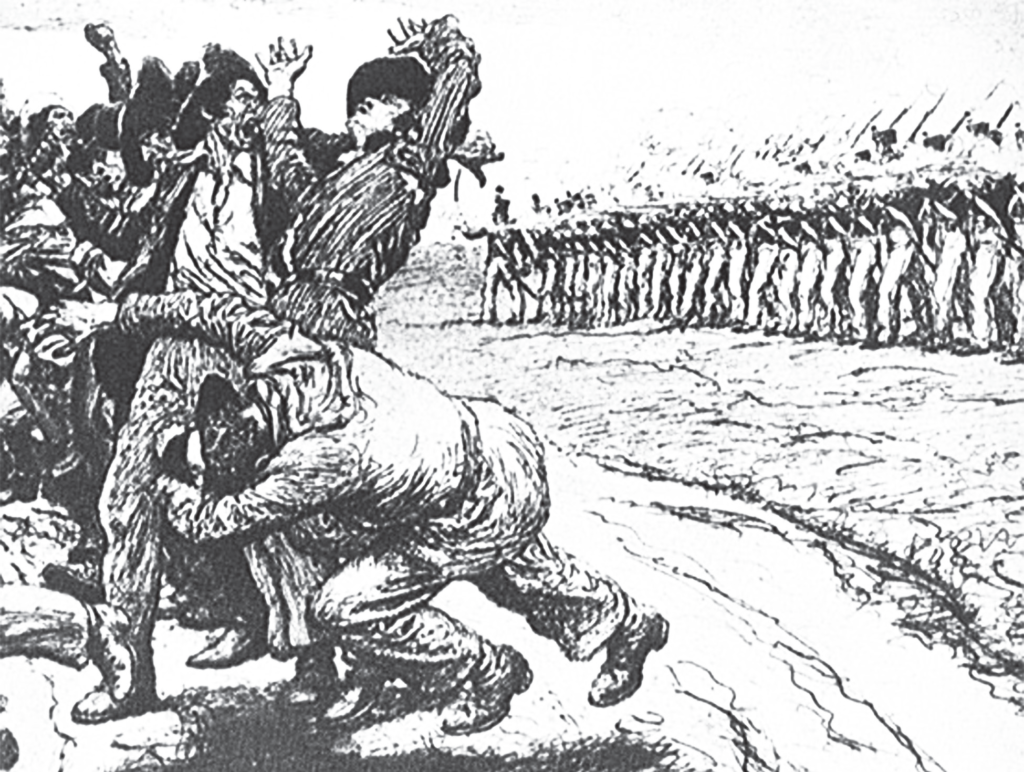

Callahan’s leadership abilities were on full display, and he was quickly promoted to sergeant in the ragtag Texian Army. Col. James Fannin led his battalion to Goliad, preparing for the Mexican Army’s arrival at the old Spanish presidio. Following Santa Anna’s siege of the Alamo on March 6, where all defenders were killed, Callahan and his fellow soldier braced for their moment of conflict. Eventually, Callahan and other Georgia Battalion member were captured and labored as prisoners in Victoria. On March 27, 1836, following the Battle of Coleto, the Mexican Army, under orders from General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, executed over 400 Texian soldiers in the town of Goliad. Well-known as a mechanic, James Callahan was spared, but he spent the rest of his life with an unrelenting hatred for Mexicans who had slaughtered his compatriots.

The Callahan Expedition

The Lipans were very strong at this time. It was said that they could put 500 warriors in the field any day. There had been rumors that this powerful tribe wanted to make peace with us, but we did not believe it. One day I looked from the door of my house and saw not less than a thousand mounted warriors not a mile away. They were mounted on gaily-caparisoned horses, and their bodies were painted as if ready for battle.

Native American Agent Robert S. Neighbors in 1848.

In central Texas, Euro-American settlements grew throughout the 1840s and 50s. But as they pushed westward, conflicts with Native tribes increased. By 1855, Lipan Apache raids had become so bad that Texas Governor Pease empowered Callahan to form a company of Texas Rangers, and strike back at the Indians who were terrorizing the settlers. Callahan and his eighty-eight men set off for a disastrous tour, which included an illegal invasion of Mexico, and in Callahan’s burning of Piedras Negras. Callahan’s defense was simply a response a Mexican ambush. Was the Lipan Apache mission a ruse? Was Callahan enacting his own justice for his fallen friends at Goliad? Callahan never again ventured across the border, and continued to serve as a Ranger captain.

Ironically, following twenty years of service to Texas, and after so many battles, James Hughes Callahan was assassinated by his next-door neighbor.