More than 14,000 state residents died that year as a result of the Indiana influenza epidemic.

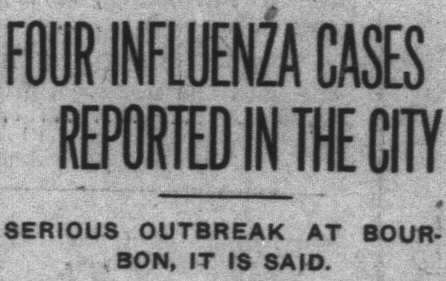

In the annals of Indiana Disasters, the Indiana influenza pandemic of 1918 stands out. The first official cases of flu were reported in Evansville on September 20, 1918. By September 25, cases were appearing in the state’s largest city, Indianapolis—and the capital city was hit harder than anywhere else in the Hoosier state.

Spread of the disease was perhaps made worse by the reaction in some quarters to preventing its spread. Public health officials were seemingly split over the value of both quarantines for people exposed to the virus and the prohibition of large public gatherings (including school, work and church). There was even disagreement about the value of cloth face masks that were distributed en masse by the Red Cross and many other community organizations.

On October 7, 1918, the Indianapolis Star carried the news that “Indianapolis schools, churches, theaters and moving picture houses were ordered closed and a ban was placed on all public gatherings yesterday by the city health board. The order is effective this morning and will be in effect for an indefinite period.”

The health board’s ban, coming as about two hundred flu cases had emerged in the city, ran into the very real problem of how to enforce it. There were many who remained skeptical about the seriousness of the flu or the methods to prevent it. Interestingly, the Star’s front-page story about the public health order ran far below ongoing coverage of World War I from across the sea.

A variety of other actions followed, including placing placards in the front yards of families who had members sick with the flu. And there was, of course, the continued rise in deaths as dozens and eventually hundreds of people fell ill and died. Mortuaries across the city were overrun and struggled to provide adequate caskets and burial rites for the departed.

In November, with the flu still raging in Indianapolis and across the nation, the city’s board of health announced that it would continue to enforce a face mask order for residents. This came after the board heard from local physicians about the emergence of more than 130 new cases in one day in the city.

Schools were also ordered to remain closed despite continued questions about the board’s authority to do so. Rebellious acts continued to be reported—in one, a South Bend, Indiana priest was arrested after he refused to call off Sunday Mass for his parishioners. Local school officials were also among those who were opposed to the strict efforts undertaken.

The same newspapers that carried questions about the actual risk of the flu also carried stories that indicated that of the more than 3,200 deaths statewide in less than two months, more than half of the affected were between the ages of twenty and forty, resulting in more than 3,000 Indiana children being made orphans.

Regardless, the pressure on health board members continued, and just a day before Thanksgiving, newspapers carried the news that the board had reversed itself and lifted the face mask order. Local schools, however, were to remain closed.

Before the Indiana influenza pandemic was over, more than 150,000 Indiana residents were infected with influenza between September 8, 1918, and March 15, 1919. Statewide, 14,120 Hoosiers died, 1,632 of them in Indianapolis during that period. The Indianapolis mortality rate of 4.6 deaths per 1,000 citizens was double that of the overall statewide rates and higher than the mortality rate for the much larger city of Chicago.

LEARN MORE: BUY THE BOOK!

WICKED INDIANAPOLIS

These are not the aspects of Indianapolis history you’ll see flaunted in visitors’ brochures. These are the abhorrent, the grim, the can’t-look-away misdeeds and miscreants of this city’s past, when bicycle messenger boys peddled through the night to link prostitutes with johns and when the bigoted masses tightened their grip on the city behind mayor and Klansman John Duvall. From the unseemly to the deviant to the disastrous, Hoosier Andrew E. Stoner brings you lives as out of control as the worst wreck at the Indy 500 with a history as regrettable as it is riveting.