For over 100 years, aviation has been a romantic mix of adventure and technology. Whether for crop-dusting, mail delivery, homeland security, or travel from one coast to the other, the airplane has been an indispensable player in the story of 20th century America. In the 1920s, aviation became a national obsession; and daring pilots, with their colorful planes, would join cowboys, pioneers, suffragettes, wildcatters, and gangsters in the pantheon of American icons.

Alaska

For some corners of the United States, airplanes were the only way in or out. The far-flung Alaskan frontier was perfectly-suited for planes. Even though the bi-plane was exhibited in 1913, it wasn’t until the 1920s that Alaska saw its share of commercial aviation and the birth of the bush pilot.

As planes improved, so did the commercial viability of Alaska — still decades away from becoming the 49th state. The Alaskan frontier had unmatched natural resources yet to be exploited.

Woolaroc

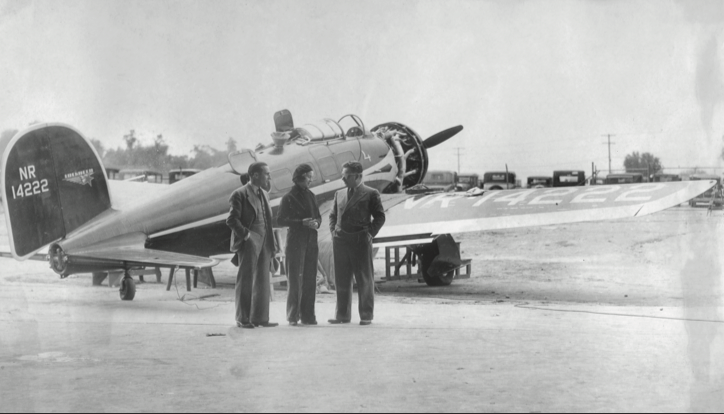

Osage Hills, in northeast Oklahoma, is home to Woolaroc, oil magnate Frank Phillips’ sprawling 3,700-acre retreat. The centerpiece was a rustic log cabin that hosted family, friends, politicians, business associates, and a few Hollywood stars. Woolaroc would also be the site of a legendary aviation tale.

Just like most Americans of that era, Frank Phillips was enamored with aviation and charged his chemists at Phillips Petroleum with improving plane fuel. In an effort to promote his new division,

The Accidental Museum

Frank Phillips’s interest in planes may have bled over into his business, but it was always personal for him. At Woolaroc, Phillips built a hangar for the Woolaroc Travel Air 5000 monoplane that Art Goebel piloted to victory in the Dole Race from California to Hawaii in 1927. It wasn’t long before the hangar became home to the oil executive’s expansive collection of American Western and American Indian art, expanding to 40,000-square-feet

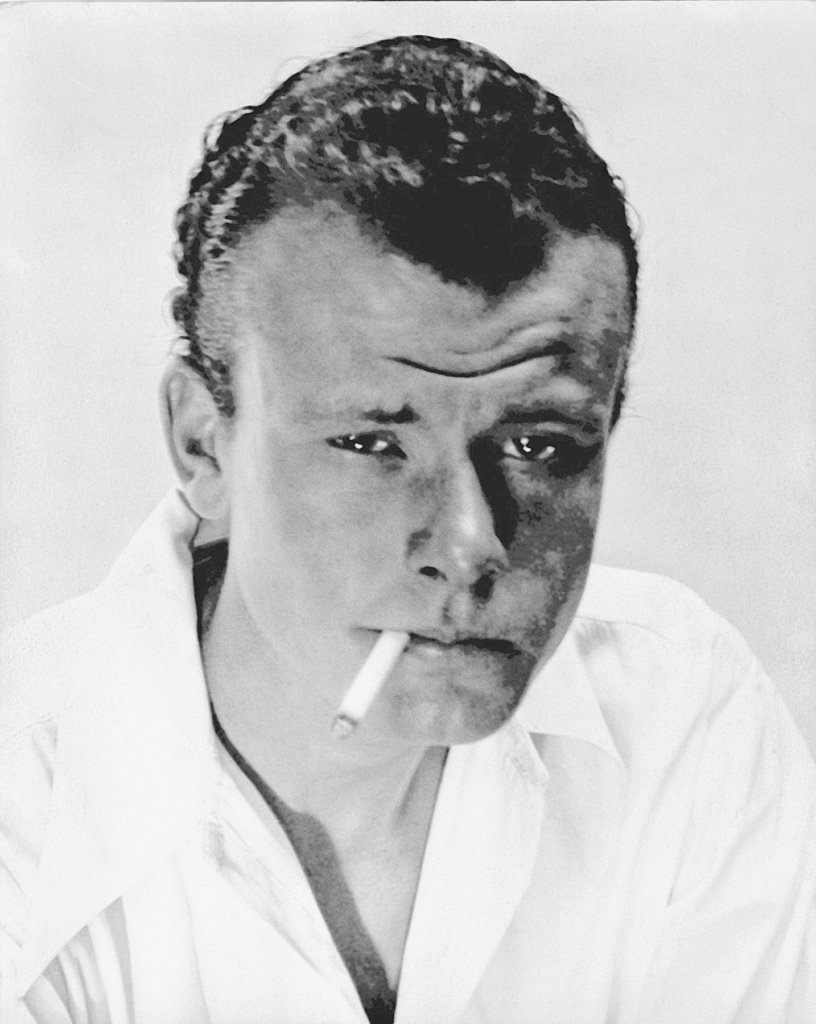

Wiley Post

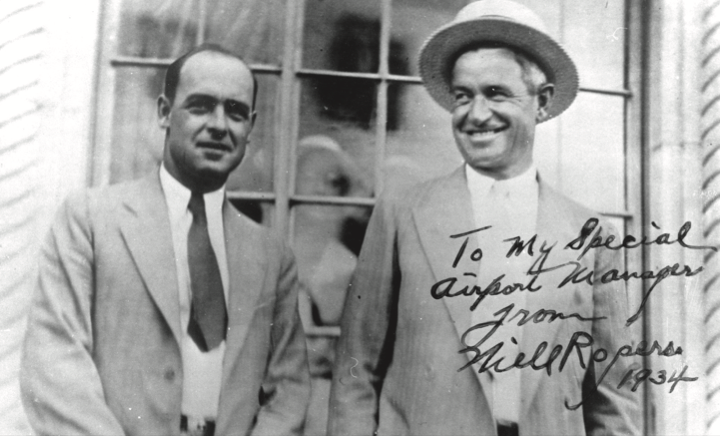

During World War I, Oklahoman Wiley Post joined the US Air Service. After the war, an oilfield accident left him with a big cash settlement, allowing the nascent aviator to buy his first plane. Always pushing the limits, Post became the first to fly solo around the world. He and fellow aviation enthusiast Frank Phillips worked towards innovations in high altitude flights, including the world’s first practical pressure suit. At Woolaroc, Post met humorist Will Rogers, and the two became close friends. And in the summer of 1935, the pair flew to Alaska, but tragedy struck. While arriving in Barrow, Alaska, their plane crashed, killing both men instantly.

Tulsa

Despite the tragedy, Oklahoma remained a hub for aviation innovation. Duncan McIntyre, who later dubbed the “father of Tulsa aviation,” came to Tulsa in 1919 and opened McIntyre Airport. Local oil men like W. G. Skelly became interested in aviation and its potential for the petroleum industry. When Tulsa Municipal Airport opened in 1928, Skelly located his Spartan Aircraft Company just one mile down the road. Oklahoma’s oil boom made the new airport one of the busiest in the world. In the early 1930s, Tulsa was home to training facilities and manufacturing. At the dawn of World War II, boomtown built Air Force Plant No. 3, where thousands of aircraft were sent for modification. In the coming decades, Tulsa remained the site for military aircraft maintenance. Both North American Aviation and Rockwell International opened facilities in Tulsa, where nearly 50 percent of the external structure of the Saturn V moon rockets were manufactured. Not bad for a boomtown on a dusty prairie.