Beginning in the 1400s, all of Western Europe was keen on colonizing North America. France, Spain, the Netherlands, and Portugal sought to claim the land and resources of the New World for themselves; and all did so, to varying degrees. For decades, North America was large enough for all of the plundering nations to snatch a piece of the un-colonized continent for themselves. Twenty years before the famous Jamestown colony of 1607, a group of English settlers arrived off the coast of North Carolina, only to be abandoned and disavowed by their countrymen. The legend of the lost colony was born.

In 1497, Englishman John Cabot, sponsored by Henry VIII, explored the Eastern Seaboard of the future United States. But it wasn’t until Queen Elizabeth herself sent Sir Humphrey Gilbert on two voyages to the New World in 1578 that England got a taste for what was waiting there. Six years later, Sir Walter Raleigh launched a more successful attempt at establishing a colony in the New World. After years of conflict on the seas, England and Spain were heading for an inevitable war.

English Colonizers

Queen Elizabeth had a different vision for colonizing the New World that contrasted with the Spanish. When engaging the Native tribes, she insisted on trade and friendship, and not conquest.

“The Spaniards have exercised most outrageous and more than Turkish cruelties in all the West Indies, whereby they are everywhere there become most odious unto them who would join with us or any other most willingly to shake off their most intolerable yoke.” — Richard Hakluyt, Discourse Concerning Western Planting

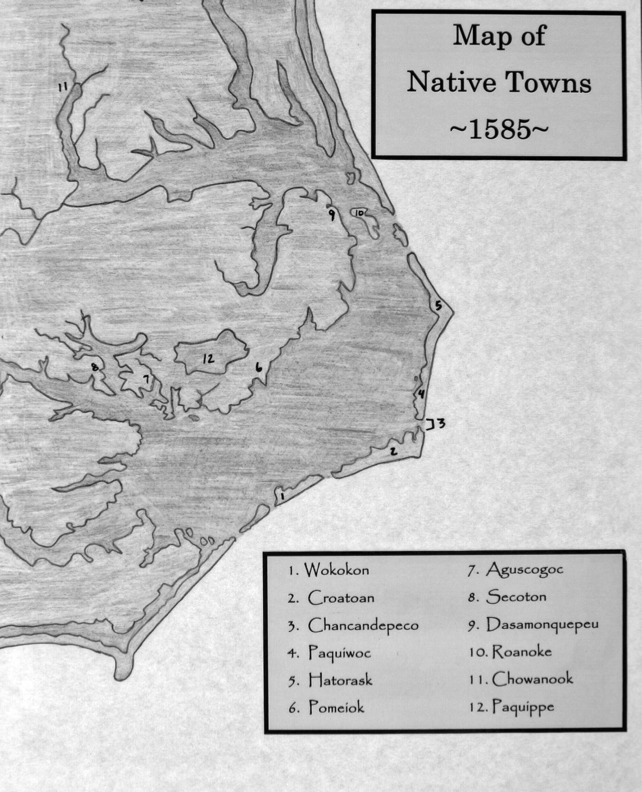

In 1584, English scouts made contact with the Croatoan and the Secotan tribes in what is now known as North Carolina. The English were showered with food and gifts through their trip and traded for pearls, tobacco, and leather. The British exploration party spent six weeks in the New World, establishing good trade relations with the Natives, all the while on the lookout for Spanish ships — this was more of a military operation than a trading venture.

The next year, British ships returned to the Outer Banks of North Carolina, where the native

A Permanent Colony

With the fourth English voyage to the New World, a permanent settlement with women and children would join the expedition, with a goal of establishing a port town — they hoped to colonize the Chesapeake Bay area, with its deep harbor. As they arrived at Roanoke Island to collect 15 missing men left behind the previous year, the Anglos were welcomed by the Croatoan, who agreed to help broker peace with hostile Native tribe the Secotans.

Abandoned

But the colonists did not move on from Roanoke to Chesapeake. Former Portuguese pirate Simon Fernando, who had offered his help, left them on the fledgling island colony and informed the Spanish forces nearby. The British Crown had a singular vision to defeat the Spanish Armada, and the colonists would be left to fend for themselves. The war would continue until 1603. But John White was still determined to find a way to get back to the colony, which included his daughter and granddaughter. When Governor John White and his crew finally made it back to the island, they found a large tree with the letters CRO carved on it. At the abandoned settlement, they found a man-made palisade, next to it on a tree the word CROATOAN was carved. Before Governor White had left earlier, these were his instructions. The friendly Croatoan was known to venture nearby, along the coastline, White’s next stop. Bad weather blew the rescue party twenty-three miles out to sea and damaged their ship. The crew refused to turn back for Croatoan and set sail for England. John White never saw his daughter or granddaughter again but took some solace that they were safe with the Croatoan.

Future search parties found no evidence that the colony had relocated to Chesapeake or in the woods west of there. Did the colonists perish, or did they assimilate with the local Natives? Some clues came in 1701 when explorer John Lawson surveyed the Native tribes in Carolina. Now dubbed Hatteras Island, Croatoan had some evidence of the abandoned colony. In fact, there were gray-eyed Indians with English-style clothes, and some had white ancestors who could read and knew of explorer Sir Walter Raleigh. The riddle of the lost colony remains unanswered but has inspired archeologists to keep digging.

Want to learn more?

Check out The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island.