Until the middle of the twentieth century, archaeology had been viewed as something pertaining to primitive cultures or lost civilizations, usually carried out in remote or undeveloped settings. Historical archaeology in America until that time had been restricted to rural or abandoned sites like Jamestown and Williamsburg in Virginia. But archaeological excavations at Independence National Historical Park in the 1950s made Philadelphia the nation’s first large urban center to be archaeologically examined. Since then, the Quaker City has received more archaeological attention than any other North American metropolis.

Urban archaeology

Digs at Independence Park in the 1950s and ’60s were meaningful to the professional archaeological community, for it had been assumed that metropolitan sites were too disturbed to produce reliable results. But the park showed otherwise, becoming a laboratory for archaeology and its interpretation, not to mention a place where archaeologists honed their skills and developed new tools of the trade. Likewise, the digs showed everyday citizens that the past might be revealed under the ground on which they walked and lived.

The work prompted the adoption of the Philadelphia Historic Preservation Ordinance and formation of the Philadelphia Historical Commission, both in 1955. The city thus became a pioneer in the field of historic preservation. More importantly, though, digging at Independence Park inspired the enactment of two federal laws for the protection of archaeological sites: the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. With its numerous historic places, Philadelphia was a prime beneficiary of this legislation, chiefly the 1966 act, which authorized the National Register of Historic Places to designate “districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects significant in American history, architecture, archeology, and culture.”

The federal laws mandated an archaeological investigation prior to construction of any project involving federal funds. Archaeologists were thus able to survey some of the Interstate 95 corridor during the freeway’s construction through Philadelphia’s central waterfront in the late 1960s. They dug into the archaeological site as wrecking balls knocked down forsaken warehouses and rowhouses around them. At the same time, collectors looking for bottles and pottery would scour the great gorge as darkness fell. Artifacts not pillaged were pulverized by bulldozers or reburied under tons of concrete.

Archaeological investigation is occurring under I-95 these days in accordance with the NHPA. Long stretches of the highway are being rebuilt in the course of the ongoing “Digging I-95” highway reconstruction project. Privy pit finds have brought to light more than five thousand years of local history, and the project has come across Leni-Lenape (Native American) artifacts dating back some nine thousand years. A pair of eyeglasses unearthed at 1026 Shackamaxon Street may very well be the oldest spectacles ever found archaeologically in the United States. The “Shackamaxon Spectacles” were probably made in Spain sometime between 1650 and 1700.

Speaking of privies, the practice of non-archaeologists exploring these wood- or brick-lined shafts for artifacts has become popular in Philadelphia. About twenty amateur archaeologists in the region can be hired to excavate backyard outhouses, a pastime that hearkens back to when day laborers routinely cleaned out privies around town. Trained archaeologists, however, maintain that privy diggers are destroying potential archaeological sites and are fulfilling personal pursuits instead of contextualizing the past.

The Sheraton Society Hill Hotel opened at Front and Walnut, next to Interstate 95, on July 4, 1986. As archaeological investigations of construction sites had become customary by then, professional archaeologists recovered more than 130 prehistoric artifacts there before highway construction.

Quaker graves

Moving west a few blocks, the Free Quaker Meeting House was raised in 1783 at the southwest corner of 5th and Arch and is today part of Independence Park. The Free Quakers splintered from the pacifist main body of the Society of Friends to support the American Revolution, even though they knew they would be “read out” (expelled) for doing so. About two hundred Free Quakers worshiped at this, the first Free Quaker Meeting House in the world. They met there until 1834, when participation waned. Betsy Ross was one of the last two members.

The structure then became a library, followed by a warehouse. Just before it was restored in the mid-1960s, the meetinghouse was physically moved about twenty feet west to its present location so as to enable the widening of 5th Street during the creation of Independence Park. The building is now an interpretive center; its original basement vaults may still lie under the intersection of 5th and Arch.

Betsy Ross died in 1836 and has been laid to rest at three different locations in Philadelphia: a Free Quaker graveyard at 5th and Locust; Mount Moriah Cemetery in Southwest Philadelphia; and in the courtyard of the Betsy Ross House on Arch Street since 1975, in preparation for the Bicentennial celebration. So Betsy Ross wandered after death as much as John Haviland. Note that no remains were found beneath Ross’s tombstone during the last move, so bones from elsewhere within the family plot were reckoned to be hers and were reinterred in the current grave.

In 2005 or thereabouts, an eight-inch cannonball was uncovered in the ground steps away from Betsy Ross’s grave site. A metal works previously occupied the courtyard of the Betsy Ross House, so the discovery is odd yet not outlandish. In addition, the sidewalk along Arch Street fronting the yard contains several large slabs of flagstone, each containing what appears to be a coal-hole cover. The pavers were once over what may have been a large basement coal vault for the metals factory taken down to create the Betsy Ross Courtyard. (Perchance the basement is still intact under the sidewalk?)

An unidentified Revolutionary veteran

Archaeological investigations had been done periodically at Washington Square, another one of the five public commons drawn up by William Penn in his 1682 plan for Philadelphia. This area was known as “Congo Square,” as it was one of few places in the city to bury African Americans in the 1700s. Additionally, more dead from the War for American Independence are interred at Washington Square than any other place in the nation—more than two thousand Continental soldiers and sailors and British prisoners of war.

The Washington Square Planning Committee in 1954 decided to put up a memorial that honored both George Washington and an unidentified soldier from the Revolutionary War. An archaeological dig in 1956 exposed the remains of a male about twenty years old inside an oak coffin, with the skull showing indications of a likely musket ball injury. This would be the body used for the unknown soldier who would repose in a stone sarcophagus at the feet of the life-size statue of Washington. Yet a nagging question persists: Was this the body of an American rebel or a British soldier? The world will never know for sure.

Archaeologists monitoring the Commuter Rail Tunnel’s construction in 1980 happened on a burial ground of the First African Baptist Church near 8th and Vine. Some 140 graves were discovered and showed traits of African burial customs, with plots often holding as many as five bodies. Ten years later, another cemetery of this church or a related one was detected at 10th and Vine during the construction of the Vine Street Expressway. These digs provided a glimpse into free African American life and death in nineteenth-century Philadelphia. Remains were reinterred in Eden Cemetery, the nation’s oldest black-owned burial ground, in Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

The Team behind the Digs

The archaeologists who worked on these Philadelphia projects included John Lambert Cotter, Daniel Roberts, and Michael Parrington. Together, they authored The Buried Past: An Archeological History of Philadelphia (1993), the first general archaeological synthesis for any major city in North America. Indeed, John Cotter became the primary founder of urban archaeology in the United States by virtue of selecting the city of Philadelphia as his laboratory. He also taught a series of courses at the University of Pennsylvania that explored Philadelphia as an archaeological site. First offered in the 1960–61 academic year, Cotter’s “Problems and Methods of Historical American Archeology” was the nation’s first course in American historical archaeology. Between 1963 and 1978, the city’s historic estates, churches, taverns, factories, prisons, and neighborhoods were sampled or fully excavated, gradually providing an outline of Philadelphia’s archaeological history.

The popularity of urban archaeology in Philadelphia continues in the twenty-first century. More than 1 million eighteenth-century artifacts were unearthed at the National Constitution Center construction site in 2000– 2001, leading one archaeologist to call it “the greatest urban archaeological find of our lifetime.” Archaeologists there further unveiled the bodies of members of the Second Presbyterian Church, the graveyard of which was located at the northwest corner of 5th and Arch from around 1750 to 1864. Although it was believed that 1,500 burials there had been removed in 1867, eighty-eight sets of relics were encountered in stacked coffins. They were later reinterred at The Woodlands Cemetery.

Fifteen coffins

In 2001, the coffins of nine adults and six children were discovered during the digging of a utility trench for replacing water pipes along the 700 block of Washington Avenue. The ground was once the remote necropolis of Old St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, of Society Hill. The cemetery opened in 1824 and closed in 1893, and graves were to have been removed when the land was sold for housing in 1905. The Philadelphia Water Department considered laying new pipes in place over the coffins, as had been done during the original pipe installation, but this was rejected. Volunteers donated time and money to move the remains to Laurel Hill Cemetery by 2004.

What happened to these burial grounds is a familiar story throughout the Quaker City, particularly the downtown area. The likelihood that a cemetery has been wherever one stands in Philadelphia is fairly high—and not surprising for a city that has witnessed so much human history. Experts contend that bodies are buried underneath buildings, homes, streets, and even parks throughout Philadelphia. For example, sixty or so graves were unearthed in 2010 during the revitalization of Sister Cities Park (within Logan Circle), thought to be from when Logan Square was a potter’s field in the early nineteenth century.

Another graveyard in the news lately is Mother Bethel Burying Ground, located under parts of Weccacoe Playground in the Queens Village neighborhood. Mother Bethel Church purchased the property in 1810 and used the cemetery until the 1860s. There was reason to believe that not all burials were moved prior the graveyard’s eventual sale to the City of Philadelphia for the site’s transformation into a community park (Weccacoe Square). Planned renovations raised questions as to whether any intact burials would be disturbed. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission requested an archaeological examination in accordance with NHPA Section 106. The 2013 investigation not only found that human remains were still on the Weccacoe Playground site but also estimated that more than five thousand bodies rested there! These were men and women who struggled to successfully establish the first major free black community in the North. The graves, only about three feet below the surface, have not been moved.

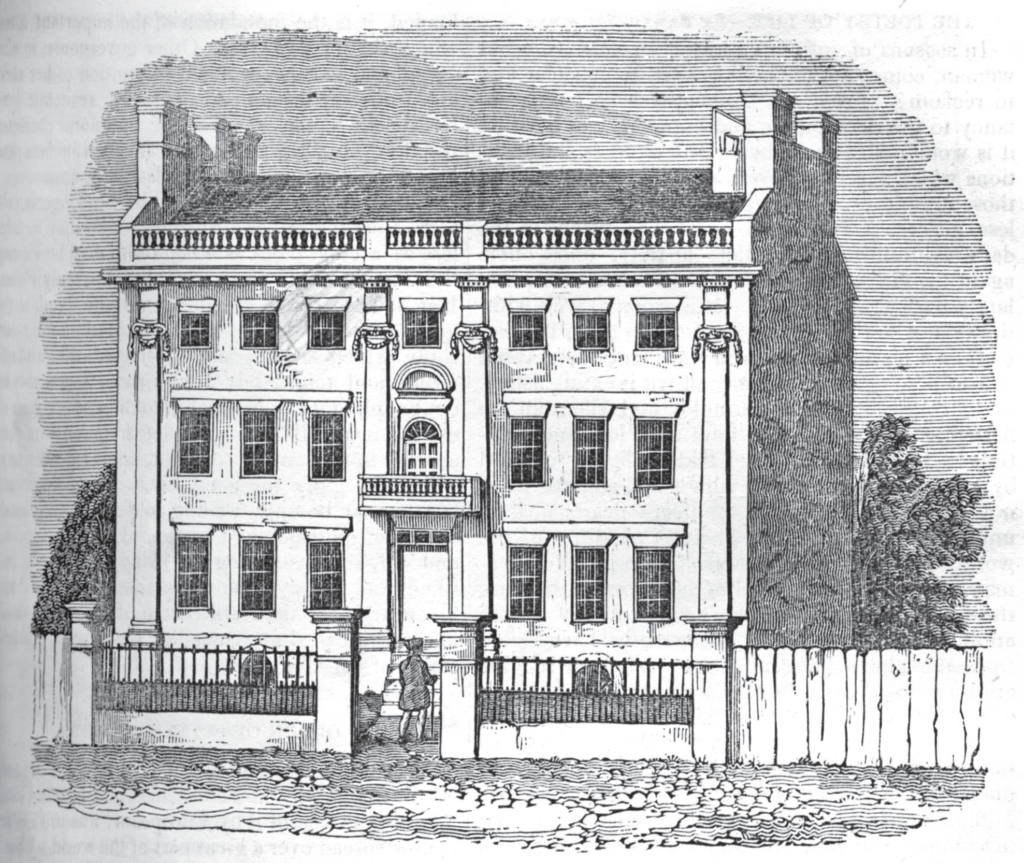

The site of the Morris House was excavated early this century, and it, too, had a connection to early African American life in Philadelphia. The finest mansion in Philadelphia, it had been built at the southeast corner of 6th and Market in the 1760s and was afterward owned by merchant Robert Morris, then the richest man in America and the chief financier of the American Revolution. George Washington frequently visited Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War and stayed with the Morris family.

The Morrises later lent the dwelling rent-free to Washington while the Constitutional Convention was in session. Washington would later pay Robert Morris $3,000 per year to live there with his family during his time as President of the United States, occupying the mansion from November 1790 to March 1797. The house was thus the nation’s first presidential mansion (the original “White House,” so to speak).

Presidential digs

President Washington remodeled the house, adding a bowed structure with windows to the State Dining Room on the southern façade. The interior of this room was semicircular, so the bow is thought to be the model for the Oval Office in the real White House. Washington may also have added an underground passage between the outside kitchen and the house for use by servants and the enslaved. Remains of this tunnel are under the site.

More than twenty people lived on the premises with the Washingtons in the 1790s, including fifteen white servants and eight black slaves from Mount Vernon. Oney Judge was a female slave who escaped to New Hampshire in 1796 while the Washingtons were having dinner. George Washington made repeated attempts to recapture her, all unsuccessful.

President John Adams lived in the President’s House for much of his term before leaving Philadelphia for Washington, D.C., in 1800. The house was subsequently used as a hotel and for mercantile purposes until it was razed in 1832. Stores were then opened on the site, including one that was John Wanamaker’s first dry goods emporium (“Oak Hall”). The land was thoroughly cleared in the 1950s when Independence National Historical Park was created, thus removing any trace of the house aboveground.

But below ground, the foundations of the mansion endured. In 2007, the National Park Service undertook an archaeology project to assess the President’s House site. A viewing area was set up so citizens could oversee archaeologists at work. The excavation attracted some 300,000 visitors, captivating Philadelphians and spurring a Congressional mandate to commemorate the house, its use during the Washington and Adams presidencies, and the slaves who toiled there.

The memorial, President’s House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation, is a pavilion that allows visitors to view the Morris House’s remaining foundations. Signage and video exhibits portray the venue’s history and the roles of slavery in the Washington household and in American culture. The site, now part of Independence Park, also highlights the early role of Philadelphia in the Executive Branch of national government.

Lastly, archaeologists made national news when they discovered more than twenty colonial-era privies and well shafts filled with eighty-two thousand artifacts during excavation work at 3rd and Chestnut for the Museum of the American Revolution. Found items relating to the Revolutionary War have been on display at the museum since it opened in 2017.

Underground Philadelphia: From Caves and Canals to Tunnels and Transit