Most Americans are familiar with the annual celebration of Groundhog Day. Every February 2nd, people gather nationwide for the yearly celebration to discover if spring is around the corner, or if they will endure another six weeks of winter. Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania’s celebration of the holiday sees the biggest crowds in the country, with more than 20,000 people in attendance, and millions more watching on television. With roots in Native lore, the contemporary celebration predates the area’s first English settlers. Here, we’re exploring the history of Punxsutawney, and what makes the city’s Groundhog Day celebration unique.

The Birth of a Tradition

The area that is today Punxsutawney was first settled by the Delaware Indians. It originally served as a campsite between the Allegheny and Susquehanna rivers, and for several years was home to tribes that moved through the area. According to the creation myth of the Delaware Indians, their ancestors, the “Lenni Lenape,” began their lives as animals in “mother earth,” before eventually emerging as humans. Oijik, or “Woodchuck,” was recognized as the grandfather of the area’s earliest inhabitants. This legend persisted through centuries, and contributed to the rise of Groundhog Day lore.

Beginning in 1723, white settlers moved into the area, and began pushing the native tribes out. In an effort to protect their land, the Delaware, Muncy, Shawnees, Naticokes, Tuscaroras, and Mingoes tribes met at the Punxsutawney lodge in 1754. Their petition resisted the sale of their land to incoming white settlers. Unfortunately, their attempt was unsuccessful. By the late 1790s, the first official white establishment was created in today’s Jefferson County. Natives helped this community learn how to hunt, plant, and live successfully off the land. However, by the early 1800s, the tribes had largely vacated the area.

Skills for working off the land weren’t the only thing Natives left behind for settlers. Their legend of Oijik became popular amongst the colonists as well. They quickly adopted the story into their own traditions, and the modern Groundhog Day celebration began to take shape.

Groundhog Day in Punxsutawney

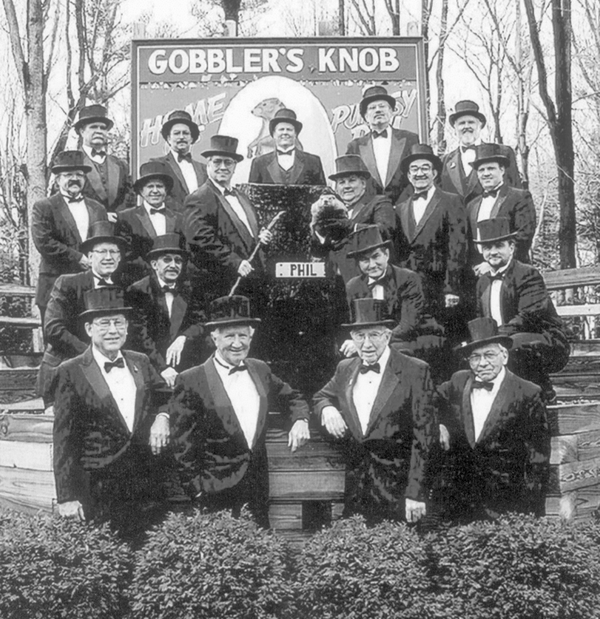

The city of Punxsutawney’s most famous resident is not a person: it’s a groundhog. Every year, Punxsutawney Phil predicts whether spring is near, or winter will remain. According to tradition, if Phil sees his shadow, he is startled back to his hole for another six weeks of winter. However, if he doesn’t see his shadow, spring has arrived. The Groundhog Day celebration has been taking place since 1887, and begins well before sunrise on February 2. Phil lives on Gobbler’s Knot. Here, an enormous festival takes place every year with food, drink, and music.

The Punxsutawney Groundhog Club Inner Circle oversees the yearly festival, and tends to Phil year-round. Members are easily recognized by their top hats and tuxedos. Every year, the vice president of the Inner Circle prepares two scrolls prior to the event – one to read if Phil sees his shadow, and one if he doesn’t. Then, on the morning of February 2nd, Phil wakes and climbs from his hole with the help of his handlers. Phil speaks to the president of the Inner Circle in a language known as “Groundhogese” and reveals if he has seen his shadow. Only the president of the Inner Circle can understand this language. In their possession is an ancient acacia wood cane which grants them the ability to translate Phil’s words. The president then indicates to the vice president which scroll should be read to the eager crowd. This reading, regardless of the outcome, results in a day-long celebration.

Little did early settlers know when they integrated Native traditions with their own that the celebration would evolve into the popular gathering it is today. Much of the longstanding history of Punxsutawney has been preserved in this tradition. Stemming from the lore of the land’s first inhabitants, the celebration of Groundhog Day is famed across the nation and remains at the heart of Punxsutawney.