For many, tales of the Wild West elicit visions of horseback riding cowboys, daring outlaws, and dusty saloons. For author Clay Coppedge, it’s the unique and often forgotten stories from Texas’ Wild West that excite him. In his book Texas Singularities: Prairie Dog Lawyers, Peg Leg Stage Robberies & Mysterious Malakoff Men, he looks at some of the strangest stories from the Lone Star State, and today has shared one of the stories of an outlaw who didn’t quite make the cut – for his book, or as a criminal!

This was one of the first stories I chose for my newest collection of Texana for History Press, but it was one of the first to go. Though Al Jennings would have fit perfectly in the “Great Pretenders” section of my book, this dude just wasn’t Texas enough. Most of his alleged and ill-advised perpetrations took place in present-day Oklahoma, though he dropped into Texas from time to time. Dangerous Al made it into the history books, just as he hoped he would, though not in the context he tried to script.

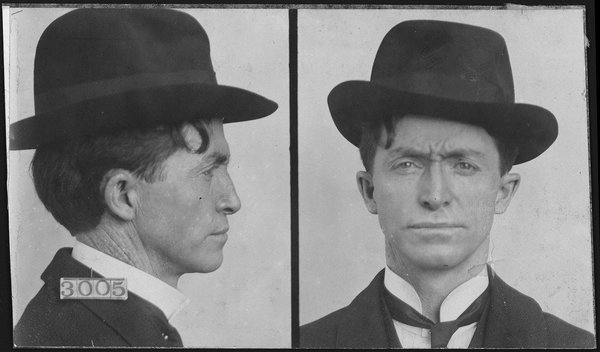

Life and Times of Dangerous Al Jennings

Al Jennings was a bad outlaw, not in the sense that he was dangerous or feared, but in the sense that he wasn’t very good at outlawry. Jennings was, however, a good storyteller, and good stories last longer than bad outlaws unless, of course, a bad outlaw is telling the story. That was the case when Al Jennings was the storyteller.

The Al Jennings stories include all manner of Old West characters, from writer O. Henry to Sam Houston’s gunslinging, lawyering son Temple Lea Houston to the Lone Ranger.

That’s a lot of ground to cover, but we’ll begin in 1895 in Woodward, Oklahoma, where Al and his brother John were lawyers, and had the misfortune to try a case against the wildly popular and successful Temple Houston, son of Sam. The Jennings boys and Houston almost came to blows during the trial, the disagreement stretching into the evening, and culminating with a gunfight that found John dead and Sam Houston’s son charged with murder.

John stayed dead, but Temple Houston won his own freedom in court, same as he did for many another alleged killer.

“The future, which seemed so bright to me as a young lawyer in a new country, died with my brother,” Al Jennings later wrote. “I reverted to the primitive man that was within me.”

The primitive man inside Al Jennings wasn’t very bright. First, he and his remaining brother, Frank, laid hands on some fake U.S. Marshall badges, and used them to charge gullible trail herders a fictional toll for driving their cattle across the territory. Amusing as that was, Jennings wanted more out of life. He wanted to be a train robber. So, he recruited a few members of the Doolin gang to help him be all he could be. The gang included Frank, Little Dick West, Dynamite Dick Clifton and the O’Malley brothers, Morris and Pat. Together, they discovered several ways not to rob a train.

One sure way to not rob a train is to stand on the tracks, waving a lantern and firing your pistol in the air. Al Jennings tried this once and succeeded only in jumping out of the way of the train before it ended his primitive phase (and all future phases) right then and there.

Jennings and the gang also figured out that safes don’t open, regardless of how hard you bang on it or how many times you shoot it. They tried that once and, when the safe failed to respond, they robbed the passengers and rode away with a jug of whiskey and some bananas.

As the brains of the operation, Jennings pondered the early setbacks and decided two things. One, it would be easier to board a train that was already stopped, rather than stopping one that was already in full locomotion. Two, he needed dynamite to get inside the safe.

At a watering station near Minco, Oklahoma, Jennings and his accomplices snuck up on an unsuspecting train, and laid a load of dynamite by the safe. Jennings lit the fuse and ran like hell. A few seconds later the entire baggage car exploded into splinters. The safe and any money that might have been in it seemed to have vaporized. The gang once again had to settle for robbing the passengers, none of whom turned out to be rich.

The gang then made a crucial and atypically wise decision – they broke up. But U.S. Marshal Bud Ledbetter found the Jennings brothers hiding under some blankets on a wagon, and hauled them off to jail. A jury convicted them, and the judge sentenced Al Jennings to life in prison.

At Leavenworth prison, Jennings befriended a bank teller from Austin named William Sydney Porter, who was in the slammer for embezzlement. Since Jennings liked to talk and Porter liked to listen, the two became good friends. When Porter left prison and began writing under the name O. Henry, one of the first stories he published was called “Holding Up a Train,” which Jennings actually wrote.

Jennings was released from prison in 1904 when President Theodore Roosevelt, who knew Al’s father, a judge, pardoned him. Jennings married, ran unsuccessfully for governor of Oklahoma, and then made his way to California, where he talked his way into the movies as a consultant and occasional actor on more than 100 westerns. He was popular on the lecture circuit, and a favorite subject for interviewers because of his remarkable stories, like the one about the time he beat Jesse James in a shooting match, a feat all the more remarkable when you consider that Jesse had been dead for many years when the alleged shooting match took place.

Jennings was 82 years old in 1945 when he sued a California radio station for defamation of character because the popular “Lone Ranger” serial had, among other grievous historical inaccuracies, belittled his talents as a gunman.

“They made me mad,” Jennings told the amused jury. “They had this Lone Ranger shooting a gun out of my hand, and me an expert.” The jurors ruled in favor of the radio station.

A few years later, he accidentally killed one of his own roosters with his trusty six-shooter while chasing down an alleged chicken thief. Neighbors called the police on Jennings again when he and the actor Hugh O’Brien, who played Wyatt Earp on TV, squared off in a showdown with blanks. A couple of years later, while showing an old friend how well he could handle a six shooter, Jennings shot the old friend in the elbow.

Jennings died in California 1961 at the age of 97. Neighbors, old friends, actors, and roosters alike probably breathed a big sigh of relief, because they had found out first-hand just how dangerous Al Jennings could be.