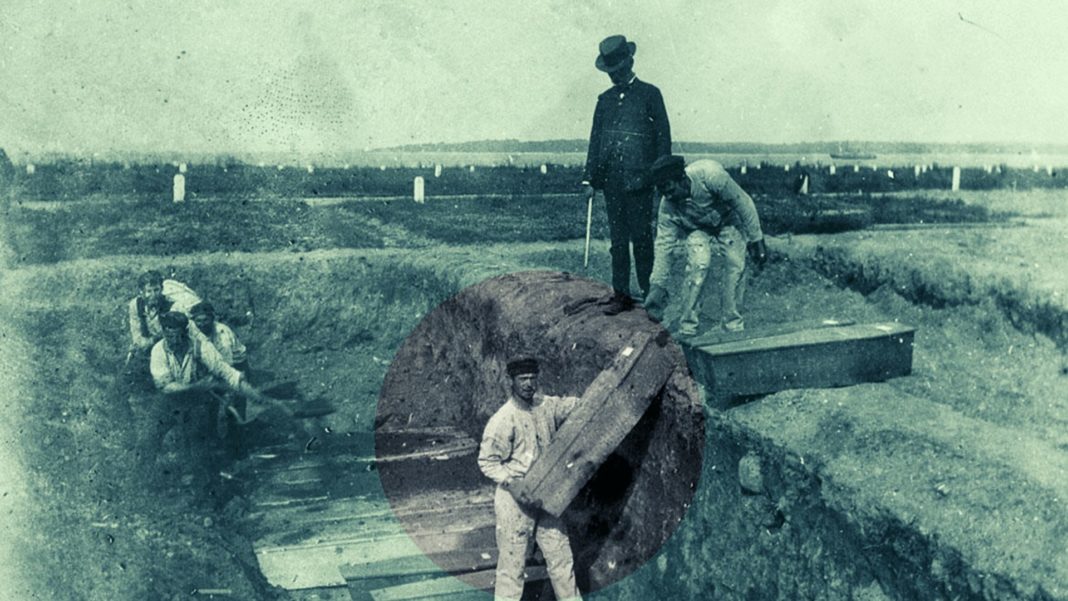

Recently, harrowing and somber images have been circulating the internet and major news outlets. In these pictures, a bulldozer is digging large trenches, while men in protective suits stack coffin upon coffin within them. These men are clearing the eternal resting space for the unclaimed victims of COVID-19 in New York City.

These images show the largest mass grave site in America, located on a tiny island in the Long Island Sound–but it’s not the first time the island was designated for such a grim task. Many are shocked to learn that over a million people are buried in New York City’s potter’s field on Hart Island. It was “rediscovered” by the general public in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy uncovered human skeletons and tossed bones into the murky river off the coast of the Island.

Though the story of Hart Island is certainly a sad one, it is rich with reminders of New York City’s past, and the lasting legacy of those who are interred there. These stories, the stories of priceless human lives, should never be forgotten.

A dramatic beginning

The earliest known group of inhabitants on Hart Island was the Native American Siwanoy tribe. In the late 1700’s, an Englishman named Thomas Pell purchased Hart Island. This land was bought and sold for private use until 1864, during the heat of the Civil War. Hart Island became a Union training facility for African American soldiers. Residence halls for Union soldiers were erected on the southern end of the island, along with a prison that could hold up to five thousand prisoners of war.

In 1868, Hart Island was purchased by the Department of Public Charities and the Department of Corrections of the Government of New York. Even today, the Department of Corrections runs operations on the island, including burials and familial visits.

Because of New York’s ever growing population, the city soon had a burial crisis on its hands. Yellow fever, smallpox and typhoid ravaged the city taking the lives of thousands. Graveyards such as the well-known Trinity Church Cemetery became overcrowded, and some people were interred less than two feet underground. The stench was horrible, and citizens took pains to avoid many cemeteries in the city at all costs.

RELATED: Murder in the Adirondacks: Murderer Jean Gianini and the Insanity Defense – Crime Capsule >

No stranger to pandemic

In an effort to, in the current parlance, “flatten the curve,” and mitigate these diseases’ effect on the city, politicians attempted to quarantine infected New Yorkers on nearby islands, including Hart Island, where a psychiatric hospital and a medical facility for tuberculosis were also erected in the late 1800’s.

Eventually, Hart Island became New York City’s potter’s field in 1869, and began mass burials in 1875 in response to the overcrowding of cemeteries within the city limits.The first person buried on Hart Island was a young immigrant named LouisaVan Slyke, who had contracted Yellow Fever.

Since then, many other mental institutions, hospitals, schools, and a Cold War missile site have come and gone on Hart Island. Prisoners from Hart Island and Blackwell Island were placed in charge of interring the bodies laid to rest there.

OTHER STORIES: Blood, Black Gold, and a town called Borger>

From Hart, to Rikers, and back again

In 1932, a prison on Rikers Island was opened, and by the end of World War II, inmates on Hart Island were all moved there. To this day, the prisoners of Rikers Island bury the dead on America’s largest potter’s field.

People of all backgrounds and walks of life are interred there. Immigrants, locals, paupers, actors, the elderly and stillborn are all laid to rest alike in tightly packed groups. A singular white marker denotes each group of one thousand coffins. People who are buried there are often unidentified, can’t afford a private burial, or have no family to claim them. But each person laid to rest there has a story to tell: a story blessed with the gift of a life, of humanity..

New York City’s Hart Island: A Cemetery of Strangers

Just off the coast of the Bronx in Long Island Sound sits Hart Island, where more than one million bodies are buried in unmarked graves. Beginning as a Civil War prison and training site and later a psychiatric hospital, the location became the repository for New York City’s unclaimed dead. The island’s mass graves are a microcosm of New York history, from the 1822 burial crisis to casualties of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire and victims of the AIDS epidemic. Author Michael T. Keene reveals the history of New York’s potter’s field and the stories of some of its lost souls.

Explore nearby history…