For a brief moment that most would struggle to call “shining,” the town of Borger, Texas was on the way to becoming one of the great boomtowns of Texas oil history. But greed and grift sent the Panhandle town on a different path.

Even stay-at-home Yankees who have never have ventured west of New England will recognize the iconic shape of the Lone Star State. When asked to identify the Panhandle, they usually succeed in pointing to the northernmost extremity that sticks out like an iron skillet. But Borger? Few could find it on a map today — but that was not the case 100 years ago, when Borger took center-stage first as an oil boomtown and eventually as one of the most corrupt towns in the Panhandle–or maybe all of Texas.

Twenty-six square counties arranged in five neat rows make up the Panhandle. In terms of geography, history and culture, it has always been the most isolated section of Texas, a world unto itself, sharing more in common with eastern New Mexico and western Oklahoma than with the rest of the sprawling state.

Well into the third decade of the twentieth century, the Panhandle was cattle country with many more inhabitants walking around on four feet than on two. Amarillo, the only town of any size, counted a mere 15,494 heads in the census of 1920 but still dwarfed a scattering of smaller communities with populations below 2,000.

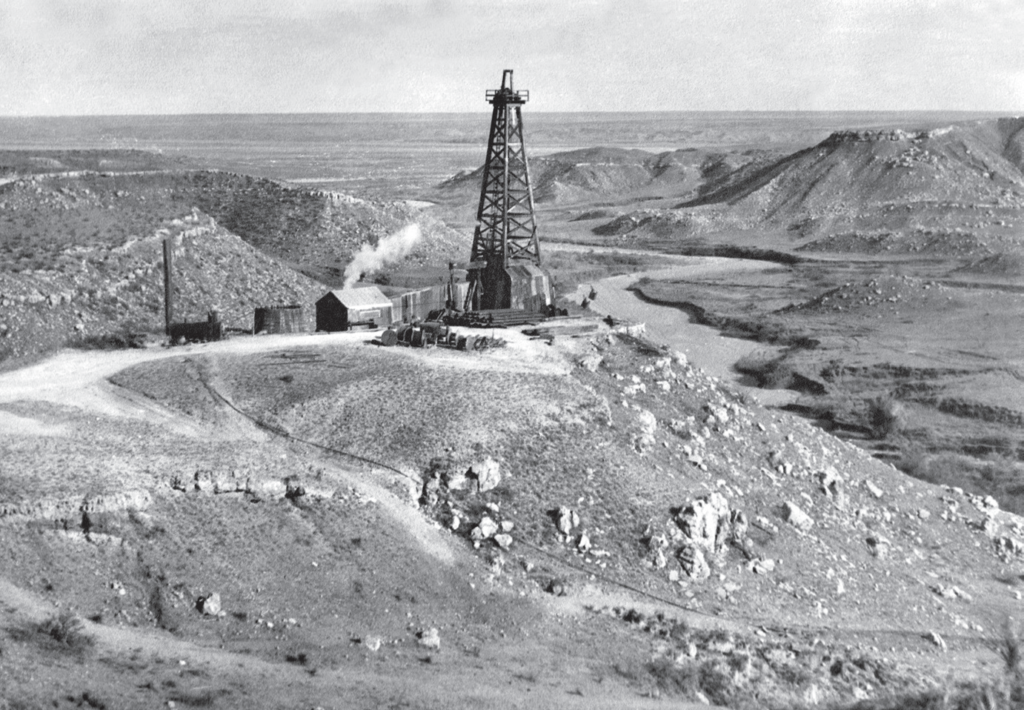

Oil came to the Panhandle in stages over eight long and drawn-out years of exploration on a shoestring budget. In 1918, a group of Amarillo businessmen, eager to imitate the instant millionaires in the eastern half of Texas, contacted a geology professor at the University of Oklahoma who had studied the underground formations in the Panhandle at the turn of the century. Even though he had been searching for water at the time, the geologist did recall an area along the Canadian River north of Amarillo that looked promising for natural gas and possibly oil.

Drilling on the businessmen’s dime, the professor found gas nine out of ten times. However, oil proved more elusive, and the first producing well was not drilled until 1923.

Halfway across the state of Oklahoma, Asa Phillip Borger could smell opportunity in the Texas Panhandle. The Missouri-born real estate promoter whom everyone called “Ace,” maybe because he always seemed to have one up his sleeve, had made a fortune in the past decade and a half by creating start-up communities from nothing and by giving a new lease on life to dying towns.

At twenty-seven, Borger was doing right well for himself with a lumberyard in his birthplace of Carthage, Missouri, but wanted more out of life—a whole lot more. So in 1915, Ace talked his brother Pete into having a go at the real estate game in Pilcher, the center of lead and zinc mining in eastern Oklahoma.

The amateurs turned a modest profit in their maiden attempt at land hawking, but the money and experience were nothing compared to their partnership with the “King of the Wildcatters.” Tom Slick Sr. was the first of a long line of oil prospectors to have that title temporarily bestowed on him.

The Borger boys teamed up with Tom Sr. in 1917 to pull a boomtown out of thin air. The wildcatter had struck it rich again, this time between Tulsa and Bristow, and needed a pair of able hands to build the necessary infrastructure from the ground up. Under Slick’s tutelage, Ace and Pete learned how to buy land on the cheap, divide it into town lots, sell the lots for a sky-is-the-limit price, organize and staff a local government under their absolute control and satisfy the wants and needs of the people who flocked to the new speck on the map.

The Borgers and Slick Sr. soon parted company, presumably on good terms and all three with fatter wallets. Ace, with Pete in his role of low-profile junior partner, exploited the next big boom in the Greater Seminole Oil Field due east of Oklahoma City. After a tumultuous interlude in Cromwell, they set their sights on the Lone Star State.

On a crisp winter day in 1926, Ace saddled his horse for a close-up look at the next big oil boom that had everyone talking. This seemingly routine speculating trip would end up altering Texas Oil History as anyone knew it. Riding to the crest of the highest hill he could find, he surveyed the barren landscape down below. There was not a single tree or man-made edifice in sight, only a solitary derrick.

But that was what Ace Borger had ridden so far to see. Oil in the Texas Panhandle was neither a myth nor a mirage, and by seizing the moment, he could be in charge from the opening bell. Ace had learned from his mistakes in Cromwell, where the people who already lived pressured him into sharing power and the spoils. In his mind, he had bent over backward to accommodate those nit-picking yokels only to have them turn on him.

This time Ace would take a page from Tom Slick’s playbook by starting with a clean slate. And like Slick, he would give his town his name: Borger.

Ace moved with lightning speed. He paid a rancher $12,000 for 240 acres, filed the obligatory forms with the state and on March 8, 1926, opened the office of the Borger Townsite Company. He ran full-page advertisements in the Amarillo dailies and the small-town weeklies under the bold headline:

“Your Opportunity Lies in Borger The New Town of The Plains.”

On Main and three other streets, 20- by 120-foot lots sold for $1,500 with a down payment of $450. At the close of business opening day, the cash receipts totaled over $60,000. In six frenzied months, the Borger Townsite Company would clear a cool million on Ace’s $12,000 in seed money.

No one can say for sure how many people ended up in Borger or when they got there. The Handbook of Texas, the recognized authority on all things Texan, states: “Within ninety days of its founding, sensational advertising and the lure of ‘black gold’ brought over 45,000 men and women to the new boomtown.” Fantastic as it may sound today, that ballpark figure coincides with other educated guesses of the time.

To put it in historical perspective, a population of 45,000 would have made Ace’s Panhandle paradise the sixth- largest city in the Lone Star State in the mid-’20s behind only Dallas, El Paso, Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio.

Borger found a place for his cronies from Cromwell. John R. Miller, his personal attorney and trouble shooter, filled the office of mayor in a sham election following incorporation in late October 1926.

Miller in turn invited “Two Gun” Dick Herwig to establish his own corrupt and ruthless brand of law enforcement with “officers,” to use the term loosely, of his own choosing. To keep the roughnecks and the rest of the oilfield labor force entertained and broke, Miller brought in Ma and Pa Murphy, two more Cromwell veterans with their obedient band of prostitutes.

While Ace publicly distanced himself from Herwig and the Murphys in order to maintain his carefully cultivated illusion of respectability, there can be no question that he personally profited from their criminal activities.

“Once again Bartee brings to life characters you never heard of before.”

Reader Review

Dick Herwig was a convicted murderer who, rumor had it, bought his way out of a long prison term in Oklahoma. True or not, the fact remained that he spent less than a decade behind bars on a ninety-nine-year rap. Herwig’s moniker came from the pair of pearl-handle revolvers that appeared to be permanently attached to his hips. Pistol-whipping was one of his favorite pastimes, which the sadist practiced on defenseless victims whenever the mood struck him

The chief deputy or town marshal—Herwig went by both titles—was as clever as he was corrupt. His network of stills produced an endless supply of rotgut whiskey that twenty-four-hour saloons like the Rattlesnake Inn and Bloody Bucket were required to buy.

“Booger Town,” as local smart-alecks referred to Ace Borger’s pride and joy, went full blast through the end of 1926. Five hundred miles from Austin, the boomtown attracted about as much attention as the dark side of the moon in the state capitol.

Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, wife of scandal-plagued “Farmer Jim” and the first woman elected governor of any state, was a live-and-let-live chief executive who pardoned two thousand Texans convicted under the state prohibition statute. She was not inclined to punish folks in faraway Borger, wherever that was, for letting their hair down.

For reasons that had nothing to do with the wild goings-on in the Panhandle, voters denied Mrs. Ferguson the traditional second term. As a Central Texas district attorney, Dan Moody had helped to turn the tide against the Ku Klux Klan with successful prosecutions of the nightriders for their cowardly crimes. Elected attorney general in 1924 at the age of thirty-one, Moody humiliated the incumbent and her impeached husband two years later in the Democratic runoff for the gubernatorial nomination, which was tantamount to victory in one-party Texas where Republicans were about as popular as horse thieves.

The wide-open boomtown in the Panhandle did not figure prominently in Dan Moody’s bid for the Lone Star State’s highest office nor did he put a Borger housecleaning on his list of campaign promises. With much bigger fish to fry, the youngest governor in Texas history could have followed his predecessor’s example and done nothing at all.

But that was not in Governor Moody’s law-and-order nature.

Moody had been in office less than three months when he sent Captain Frank Hamer of the Texas Rangers (who would later bust the “Texas Chicken Ranch” that inspired The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas) on an inspection tour of Borger. Two days later, on April 6, 1927, the future bushwhacker of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker reported, “The worst crime ring I have seen in my 23 years as an officer exists in Borger.”

That was all the governor needed to hear. Moody dispatched eight Rangers under the joint command of Captains William W. Sterling and Tom Hickman to Borger with crystal-clear orders not to return “until the lawless unconditionally surrender.”

On April 17, the day Sterling arrived, an inquisitive reporter asked how the legendary lawman planned on making the bad guys behave. He answered that the Rangers were “Where the criminals have been killing officers, we are going to kill off some crooks.” That rhetorical shot over the bow sent practically all of the gamblers, bootleggers, pimps, prostitutes and other parasites packing.

Fearing the state cops would be coming for him, a safe bet under the circumstances, “Two-Gun” Dick Herwig skipped town with his ill-gotten gains. But he made two dumb mistakes: First, Herwig stopped far too soon—less than ten miles inside New Mexico. Second, he bought a roadhouse and thumbed his nose at Lone Star authorities with a giant sign that declared: “Eight Miles From Texas Rangers.”

Meanwhile in Borger, the Rangers, backed by a beefed-up contingent of U.S. marshals and Prohibition agents, dismantled the criminal infrastructure piece by piece. Two dozen bars and gambling joints were shut down tighter than a drum, a river of illegal spirits was seized and dumped in the nearest gutter and the stills that produced Herwig’s official whiskey and beer were destroyed. Several hundred federal offenders were rounded up and marched to a domino parlor where they were given the choice of Leavenworth or voluntary relocation. Their duty done, the feds left town and the Rangers in charge, and at the end of the month—April 1927—they proclaimed Borger to be “100 percent better.”

As a rule, the Texas Rangers were sharply critical of local law enforcement. Even on those occasions when the police and sheriff were honest and aboveboard, the Rangers felt they rarely measured up to their own high standards.

However, prior to the decontamination of Borger, the Rangers encountered a police chief they came to accept as an equal. The Ranger trio assigned to the northern Panhandle needed canine assistance in tracking down the killer of the wife of a gas station owner, and the closest bloodhounds belonged to the police chief at Plainview, 125 miles to the south. H.H. Murray was happy to lend a hand, or in this case a paw, and drove to Borger the next day—January 16, 1927—with his three dogs.

The bloodhounds picked up the suspects’ scent but lost it in the derrick- covered countryside. The case grew cold, causing the Rangers and the Plainview policeman to reluctantly go their separate ways.

No one could have blamed Chief Murray for forgetting all about the unsolved homicide. Borger was miles out of his jurisdiction, and there was no shortage of cases for him to crack back home. But the coldblooded killing of a woman stuck in his craw, especially since he knew from experience that neither the Hutchinson County sheriff nor the Borger police department would do a thing to bring her murderer to justice.

Two months passed without a glimmer of hope. In fact, the hunt for the killers lost ground after the Borger cops misplaced the only hard evidence, the two bullets removed from the victim’s body. The dejected chief was on the verge of throwing in the towel, when a trusted informant tipped him off to the identity and whereabouts of the triggerman.

Murray jumped in his cruiser, drove like a demon to Borger and arrested Scotty Hyden in his hotel room. He dragged his handcuffed prisoner kicking and screaming to the city jail and handed over the well-known bank robber with the full knowledge “that the moment my back was turned he would buy himself out.”

The chief waited down the street to foil the staged “escape,” which would give him the legal grounds to take Hyden to a real jail that did not have a revolving door. Less than half an hour after the booking, Murray saw his former prisoner running down the street with two cops huffing and puffing in phony pursuit. They even fired a few rounds to make it look good, but the visiting lawman could not help but notice that every shot was aimed at the ground. Murray got his man for the second time that night and transported him to another county that did not have an open-door policy.

And that was how H.H. Murray earned the respect of the Texas Rangers. The Rangers lingered for another month in Borger before notifying the governor in early June 1927 that their presence was no longer required. The boomtown was now on the straight and narrow, and they were confident it would stay that way.

Manuel T. Gonzaullas, who achieved the distinction of being the first Texas Ranger with a Spanish surname, strongly disagreed with that optimistic assessment. On loan to the Bureau of Prohibition, Gonzaullas found out that lower-profile members of what he called the “conspiracy and ring” still held important positions in the city and county governments. He went on to predict that left to their own devices those individuals would reinstate the worst excesses of the wide-open period.

“Lone Wolf,” the nickname that made Gonzaullas famous, had it right. Those criminals, who stayed in town and waited out the Rangers, ended their law-abiding masquerade and sent word to departed colleagues that the coast was clear. In three short months, it was business as usual in bloody “Booger Town.”

In the absence of outside watchdogs, some backsliding was to be expected. That was why Moody was not alarmed by intermittent complaints from irate residents that vice and violence had returned to Borger. What town in Texas did not have backrooms where grown men could wet their whistles, place a bet or pay for the company of a willing woman?

When the Texas legislature created a new judicial district in the Panhandle in the fall of 1927, Moody picked an old classmate from his law school days at the University of Texas as district attorney. The governor warned Curtis Douglas up front that he had to be tough on the criminal element in Borger and made him swear he would stay on the wagon for the duration of his term. Douglas failed miserably and Borger backslid even more. The shamed DA submitted his resignation on September 13, 1928, and John A. Holmes, a force of an attorney was waiting in the wings, setting the wheels in motion for the a chapter in Texas oil history that reads like a pulp mystery novel.

It did not take long for all parties on both sides of the law to realize the new district attorney was cut from a radically different cloth. John A. Holmes had prior experience as a Panhandle prosecutor and for the past year had been in private practice in Borger. The forty-two-year old attorney was a devoted family man with a wife and a young daughter. Much more important than his biography were two established facts: the new DA could not be bought, and he was immune to intimidation.

Thinking Holmes was too good to be true, the cynical crime lords put his squeaky clean reputation to the test. To their surprise, he turned down every bribe. Hoping to scare him into playing along, they utilized a variety of threats including the oft-repeated prophecy that he would not live long enough to finish his term. Faced with an honest and fearless man with the power to do them harm, they marked him for death.

The assassination of John Holmes made front-page news throughout the state of Texas and across the country and remains one of the most shocking chapters in Texas oil history. Newspapers that normally buried Panhandle datelines in the back pages, if they gave them any ink at all, broke the shocking story with banner headlines: “Borger Prosecutor Shot And Killed,” Waxahachie Daily Light; “Police Seek Clue in Borger Killing,” Brownsville Herald; “Concealed Slayer Shoots Down District Attorney at Borger in His Yard,” WacoNews-Tribune.

The dedicated DA had worked late into the evening on September 13, 1929—the first anniversary of his appointment—preparing cases for presentation the next morning to a grand jury at Stinnett, the county seat. A few ticks after ten o’clock, he turned into the driveway of his stucco house and coasted into the one-car garage. Seconds later, he stepped out into the moonlight and closed the garage doors.

The lone assassin, who had waited patiently since sunset, took aim with a .38-caliber pistol from his hiding place in a clump of thick bushes. He fired five rounds in rapid succession, grazing Holmes’s chest with the first, penetrating his rib cage on the right side with the second and hitting him in the back of the neck with the third. A rush of adrenalin must have caused the gunman to miss completely on the fourth and fifth attempts, but it did not matter.

Jumping out of the bushes, the killer calmly checked the bullet-riddled body for signs of life. Finding none, he rifled through the pockets of the dead man’s coat for any incriminating papers until interrupted by the screams of the woman he had just turned into a widow. He scrambled over a fence and sprinted down the alley before anyone could get a good look at him.

Dan Moody reacted with cold fury to news of the murder of John Holmes, denouncing it as “a dastardly crime of a low-life assassin” and “one of the worst crimes ever committed in Texas.”

No less enraged was the federal judge who presided over the Panhandle. In a speech to Amarillo business leaders shortly after the slaying, Judge James C. Wilson said, “In my opinion, the murder of Johnny Holmes was the most serious crime in the history of Texas in 30 years, and I believe the hand that fired the shot either was the hand of an official or had official sanction.”

At the governor’s behest, Ranger captains Hamer and Hickman made a whirlwind return trip to the boomtown they thought they had tamed. It was clear to them after a couple of days in “Booger Town” the situation had deteriorated so much over the past two years that it was impossible to tell the Rangers had ever been there at all. In his written report to Moody, which was leaked to the press, Hamer contended Borger had “the worst bit of organized crime” he ever had seen.

In nearby Amarillo the Daily News chimed in with an editorial of its own that addressed the elephant in room: martial law. “While the gravity of the Borger situation, brought to a head by the murder of District Attorney Johnnie Holmes, is not to be minimized, there seems little justification for such a drastic measure as martial law.”

The editor then proceeded to contradict his caution against minimizing the wretched state of affairs: “Sending troops to Borger would give the city a black eye before the rest of the country that is undeserving. There have been numerous murders in Borger, and there have been ugly threats and allegations smacking of a conspiracy in lawlessness. But Borger’s history is largely the history of every other oil field city.”

The twisted logic of the Amarillo daily had been prompted by the September 25–26 visit of General Jacob F. Wolters, commander of the Texas National Guard. Before he placed Borger under martial law and sent in citizen-soldiers to occupy the town, Governor Moody wanted to see if Wolters was of the same mind.In a clandestine meeting at an undisclosed location in Austin, General Wolters reported his findings in person to the governor. He made the case for military intervention, but stopped short of advocating it.

“You have given me the facts, but you have not volunteered any recommendations,” an exasperated Moody said. “If you, having investigated the situation, were Governor of Texas, would you declare martial law?”

Backed into a corner, Wolters responded with a direct two-word answer: “I would.”

Dan Moody nodded in agreement and obvious relief. The matter was settled, and the decision was made. The governor gave the general three days to get all his ducks in a row. The Guard would leave for Borger on Sunday, September 29.

As per the governor’s instructions, preparations for the mobilization were made in strictest secrecy. For the mission, thirteen officers and eighty enlisted men, unmarried and with no dependents, were handpicked from the Guard units based in Dallas and Fort Worth. Dressed in civilian clothes, they were ordered to assemble at six o’clock Saturday evening at the Cow Town armory. The Guardsmen had no idea where they were going or why or for how long. Officers kept the men busy with drills until the midday mess. At two o’clock in the afternoon, a train with three Pullmans and a baggage car pulled onto the siding next to the armory.

With nothing but time on their hands, the Guardsmen speculated on their destination. The sun in their eyes meant the train was headed west. Those who kept up with the news said that had to mean Borger, where someone had gunned down a prosecutor.

In those days, newsmen made a habit of hanging around train stations. Sometimes it yielded a scoop, as it did late that sleepy Sunday for a cub reporter in Wichita Falls. When the westbound train chugged into the station, two curious things caught his eye. First, the passenger cars were full of clean-cut young men without a woman in sight. Second, every one of them stayed in his seat instead of hustling onto the platform for a pack of cigarettes or a snack like ordinary travelers.

The excited young journalist ran to the nearest pay phone and filed his story. In a matter of minutes, the wire services hummed with the breaking news that a trainload of National Guardsmen had been sighted on a westerly course for the Panhandle. Texas oil history now had its first true-blue, state-wide scandal.

In the capital, the press corralled the governor and gave him a chance to deny the report. When the interrogators refused to accept “no comment” for an answer, Moody conceded the cat was out of the bag with this good- natured quip: “Come around tomorrow, and I’ll show you the proclamation.” The train rolled into Amarillo at four o’clock in the morning on Monday the thirtieth of September. The officers and men rubbed the sleep from their eyes and filed into the Santa Fe station, where a hearty breakfast was waiting. They ate their fill, changed into their uniforms and climbed back on the train.

At half past eight, the National Guard express pulled into Borger. The Guardsmen had been on the ground for no more than a minute when a drunk staggered up to one of them. Without a word or a verbal order from his superiors, the soldier made the first arrest of the occupation.

That was exactly the kind of first impression Wolters wanted to make. The message was that the Guard meant business, and everyone who watched the unfortunate barfly be led away got it loud and clear.Like a well-oiled machine, the Guard shifted into high gear. City hall, police headquarters and the jail were under the complete control of the military by nine o’clock. Every official, from the mayor on down, was locked out of his office and physically removed from the premises. All members of the police force were relieved of duty, stripped of their badges and firearms and told to clear out.

On Tuesday, October 2, General Wolters named the nine members of the military Board of Inquiry, empowered to look under every rock for wrongdoers, first and foremost the party or parties responsible for the murder of DA Holmes. The board did not beat around the bush but went straight to work, questioning eleven city and county officials in a grueling fourteen-hour session.

The Rangers and the rank-and-file Guard were busy, too. On October 2, in “the beginning of the actual cleanup,” according to an Amarillo paper, “at least 36 saloons, blind tigers [speakeasies], gambling halls and houses of ill repute” were raided and presumably shut down. At the end of the following day, the number of raided establishments had risen to forty-five with one hundred persons of both sexes behind bars on a laundry list of charges.

A delegation of Borger’s “best,” citizens purporting to be upright pillars of the community, asked for a meeting with General Wolters on Saturday, October 5. They wanted to know what else had to happen for the state of martial law to be lifted.

Fortune. Corruption. Innovation. Murder.

and so much more.

You think you know the story of oil in Texas, but you’ve never heard it told like this.

This article was adapted from Texas Boomtowns: A History of Blood and Oil by Bartee Haile

Wolters’s answer was clear and to the point: “The resignation of the sheriff and all of his deputies, the resignation of the two constables and their deputies, the resignation of the mayor and the commission, and all members of the police department, and the replacement of these officers by men satisfactory to District Attorney Clem Calhoun.”

The general had laid his cards on the table, and now the marked men had to play the hand or fold. Most of the small fry dropped out almost immediately, turning in their resignations and quietly leaving town. But the bigger fish, like the mayor and sheriff, dug in their heels and refused to knuckle under.

The only thing holding up the mayor’s and the sheriff’s capitulation was their fear of prosecution for crimes committed while in office. Wolters gave them his word they were free to leave town as soon as he had their resignations on the table in front of him. Two minutes later, the last remaining obstacle to the end of martial law in Borger had been eliminated.

The mayor did not go quietly, however, and insisted upon playing the martyr to the bitter end. Repeating almost word for word the statement made by the state representative when he took his leave early in the occupation, the mayor whined, “Some man or men of necessity had to be the ‘scapegoat’ for the wrath of Dan Moody, and it so happened that I, among a few other officials, was chosen for the ordeal.”

Martial law officially came to an end on the afternoon of October 18, 1929, with the long-awaited departure of the National Guard. There was no parade or public celebration other than a collective sigh of relief from the remaining residents, who, for the first time in the history of the boomtown, had control of their community.

As for Ace Borger, the string-pulling town founder came out of the crackdown smelling like a rose. Acting as if nothing had happened, he went back to being Borger’s business leader and political power broker. “How do you run a man out of town when he owns most of it?” was the question that stumped Ace’s enemies. In the end, they had no choice but to tolerate his presence.

Everyone except Arthur Huey, the county tax collector, who hated Ace Borger with a passion only blood could quench. What evidently turned Huey’s loathing into homicidal rage was Borger’s refusal to bail the sticky- fingered taxman out of jail after his arrest on an embezzlement charge.

As part of his daily routine, Ace always went by the post office to pick up his mail. Huey knew that and was waiting from him on the last day of August 1934. Borger had his head down and was thumbing through the envelopes when he heard a familiar voice yell, “You son of a bitch, get your gun!”

Ace looked up to see Huey already had the drop on him. Before he could reach for his concealed pistol, the taxman fired two shots, hitting his nemesis in the body with both. Gravely wounded, Borger slumped to the floor, but his attacker kept on shooting until the smoking Colt .45 was empty. On the off chance his victim had a flicker of life left in him, the killer borrowed Ace’s .44 from under his coat and finished him off with four rounds from his own gun.

Standing over the dead man, Huey was heard to say, “Well, you SOB, I got you this time!”

At his murder trial that December, Arthur Huey’s lawyer tried his best to sell a plea of self-defense. To his surprise, as well as his client’s, the jury found in favor of the defendant and acquitted him of the cold-blooded, premeditated killing. The not-guilty verdict mirrored public opinion in a community where the majority felt in their bones that Ace Borger, the greedy genius behind the boomtown nightmare, had it coming.

The history of Borger was written not in oil but blood and measured in coffins instead of barrels. And while Borger never met the production of Spindletop or the repute of Beaumont, the story of Borger is a key part of Texas oil history — warts and all.

This story was adapted from a chapter of Texas Boomtowns: A History of Blood and Oil by Bartee Haile. For the full story, get the book — this crazy story only scratches the surface!

ABOUT THE BOOK:

On January 10, 1901, Beaumont awoke to the historic roar of the Spindletop gusher. A flood of frantic fortune seekers heard its call and quickly descended on the town. Over the next three decades, Texas’s first oil rush transformed the sparsely populated rural state practically beyond recognition. Brothels, bordellos and slums overran sleepy towns, and thick, black oil spilled over once-green pastures. While dreams came true for a precious few, most settled for high-risk, dangerous jobs in the oilfields and passed what spare time they had in the vice districts fueled by crude. From the violent shanties of Desdemona and Mexia to Borger and beyond, wildcat speculators, grifters and barons took the land for all it was worth. Author Bartee Haile explores the story of these wild and wooly boomtowns.