In 1619 — a date that the New York Times has recently made famous and essential–a group of 32 African men, women, and children arrived on the shores of Virginia. They had been kidnapped in the royal city of Kabasa, Angola, and forced aboard the Spanish slave ship San Juan Bautista. After the ship was attacked by privateers, the captives were taken by the English to their New World colony in Virginia.

This group has been shrouded in mystery and controversy ever since. The white people who enslaved them began the brutal practice that would one day drive the nation apart, and that still shapes so much of American life today. But what do we know about that original group?

Searching For Records

The English people who arrived in 1607 and 1620, in Jamestown and Plymouth Bay, were well documented. Their names were recorded on ship manifests, musters, and census records.

Conversely, when the Angolans left Africa from the time they arrived in English North America, they were destined to be nameless individuals, intended as nothing more than chattel property on the massive agricultural farms of New Spain or Brazil.

When the Angolans came to Virginia, they temporarily disappeared into obscurity. For some, their African birth names are lost to history.

However, the Angolans began to reappear in the colony in the most unusual ways: through the ledgers of the headright system, through subsequent census records, and from legal documents left behind by various county courthouses.

An Invaluable Census

It is from these colonial records, as well as the records of the Virginia Company in England, that we can begin the long and arduous journey of unmasking and preserving their identities and legacies.

In a letter, a colonist named John Rolfe spoke of “20 and Odd” slaves arriving in America. But there’s a better measure — a census known as the Muster of 1620. This census enables us to construct crucial clues as to the men, women, and children who were originally on the San Juan Bautista.

Related: The Mystery of the Sea Islands: Gullah Geechee Legacy

Although this census does not provide the names of any of the Angolans, it does serve as the basis going forward to measure their relative numbers in the colony. It lists 892 Europeans, four Indigenous Americans, and 32 Angolans — 15 men and 17 women.

The population was categorized as either Christian (meaning white) or non-Christian (meaning non-white).

Going Deeper

In that same letter, John Rolfe explained that George Yeardley, the British Governor of Virginia, and his associate Abraham Piersey had taken many of the Angolans to their plantations. For example, Yeardley kept six slaves at his thousand-plus-acre plantation, Flowerdew, plus another two at his town home in Jamestown.

Yeardley and Piersey clearly saw their political positions as a way to achieve personal gain. They needed workers on their plantations, and they enthusiastically enslaved the Angolans and kept them for themselves. To these men, the Angolans were not human beings but economic resources.

But those colonial records sometimes preserve the slaves’ names. They were human beings, with names like John Geaween, Juan Pedro, Antonio Johnson, and Maria Johnson, to mention just a handful of those few dozen Angolans–the people who were captured and brought to America as its first set of slaves.

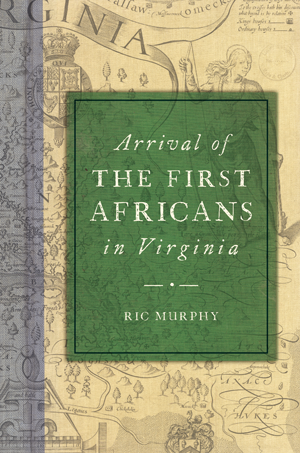

Eager to learn more? Check out Arrival of the First Africans in Virginia and other similar titles below at arcadiapublishing.com!

Eager to learn more? Check out Arrival of the First Africans in Virginia and other similar titles below at arcadiapublishing.com!