The following is excerpted and adapted from The Thibodaux Massacre: Racial Violence and the 1887 Sugar Cane Labor Strike by John DeSantis, Foreword by Burnell Tolbert.

About the Book: “On November 23, 1887, white vigilantes gunned down unarmed black laborers and their families during a spree lasting more than two hours. The violence erupted due to strikes on Louisiana sugar cane plantations. Fear, rumor and white supremacist ideals clashed with an unprecedented labor action to create an epic tragedy. A future member of the U.S. House of Representatives was among the leaders of a mob that routed black men from houses and forced them to a stretch of railroad track, ordering them to run for their lives before gunning them down. According to a witness, the guns firing in the black neighborhoods sounded like a battle. Author and award-winning reporter John DeSantis uses correspondence, interviews and federal records to detail this harrowing true story.”

Thibodaux, Louisiana

November 23, 1887, 7:00 a.m.

Bleeding from his chest and right arm, Jack Conrad squeezed himself under the simple wood-framed house on St. Michael Street as members of the mob, maybe fifty strong, kept on firing, clouding the air with acrid smoke. “I am innocent!” the fifty-three-year-old veteran called out, protesting that he had nothing to do with the strike of sugar laborers, nominally the cause of the violence. He pressed his chest against the cold ground and felt hot blood pooling beneath him. Another ball ripped through Conrad’s flesh, and he pushed his face against the earth and weeds.

Nearly a quarter century had passed since Jack and other members of the Seventy- fifth U.S. Colored Troops stormed Port Hudson, doing a job the white senior officers did not believe possible, wresting the high ground from the Rebels and opening up the Mississippi River for Yankee gunboats. They fought for their own freedom, hoping a better life would result. But the war’s outcome made little difference on the sugar plantations. Now, here he was, cornered like a cur beneath his own home, playing dead while bullets whizzed and hot, spent cartridges plinked onto the dusty street, the scuffed boots of the regulators and the hooves of their cantering, spooked horses a breath away.

“He is dead now!” one of the men called out. “Let us go.”

The voices trailed off as the mob moved on to a house on Narrow Street. More shots rang out amidst wails of women, shouts of men and the unceasing cries of babies. The chronic cough, the one that made Conrad’s war buddies joke that he would die of consumption, had to let loose, scraping exposed shards of shattered collarbone deeper into raw, bleeding flesh.

A pair of arms—Jack wasn’t sure whose—pulled him out from under the house and

carried him inside.

Jack Conrad was one of many people shot in Thibodaux, Louisiana, on November 23, 1887, although he, unlike many other victims, lived to speak of what is now called the Thibodaux Massacre.

White regulators, angered by a month-long strike of mostly black sugar cane workers in two Louisiana parishes, evicted from plantations and taking shelter in Thibodaux, spread terror and death. Some of the perpetrators and their supporters—identified in this book—were from some of the most upstanding families in town. Some of their descendants to this day hold positions of power and esteem. Records disappeared. Nobody was ever held accountable.

Multiple accounts of the day say the shooting went on for nearly three hours throughout the neighborhood east of Morgan’s railroad tracks, called to this day “back-of-town,” then—as now—home to many African American families.

A diluted account of what occurred is contained in a journal kept by the priest of Thibodaux’s Catholic church, the French-speaking Very Reverend Charles Menard. Each year since 1849, when he first arrived in Thibodaux, Père Menard penned a summary of the year, baptisms of children, the burials of the Catholic dead and other events of note.

His journal for 1887 relates that a large tomb was built at the center of the church cemetery for the priests who might wish burial there. It describes in detail the tomb-blessing ceremony, marked by a procession with six banners and ranking church officials. It then makes reference to the strike and the violence, the victims of which most likely were left in little more than shallow graves, with no tombs or markers to note that they had once labored and lived:

There was a strike, directed by the famous Knights of Labor, from the North. It concerned raising the wages of those who work during the sugar cane grinding season. The negroes, the large majority being simple and very ignorant allowed themselves to be led by bad advisors. Some of them went out on strike and wanted to prevent the others from working. There was much concern among the planters who foresaw the possibility of their abundant crop being lost by what could be a very disastrous delay in grinding. They were obliged to find new workers

and to take precautions for their protection against violence from the strikers. Several shots were fired at the non-striking workers during the night and several were slightly wounded. Militia companies were organized. A militia company with a machine gun came from New

Orleans. Thibodaux was flooded with striking negroes, who began to make threats to burn down the place. It became necessary to place guards throughout the town. Everyone armed himself as best he could. On Nov. 23, about 5 o’clock in the morning, a picket of six men stationed on the edge of town was fired upon. Two of them were seriously wounded…

This fusillade angered the other guards who rushed to the scene and began firing on the group of negroes from whence the shots had come. It was every man for himself. A dozen were killed and there were some wounded. The day passed with marches and countermarches to force the

unemployed negroes and those without a domicile to evacuate the town. All left promptly to go to the country. The negroes realizing that they had been tricked and duped went to the plantations and asked for work without conditions. Thus was concluded the famous strike which was bad for both the planters and the workers. Grinding proceeded in calm and peace to the satisfaction of all.

The mainstream press, just like Père Menard’s journal, did little to relate the true horror of the attack now known as the Thibodaux Massacre,instead perpetuating a belief that it was a regrettable but excusable—even justifiable—indiscretion. His estimate of a dozen killed, like the official acknowledgement of eight dead, is in all probability another understatement. New, credible accounts of the massacre include estimates that the shooting went on for somewhere between two and three hours. Estimates of eight to a dozen dead, given that information—which is consistent with other accounts from totally different sources—are inadequate. Suggestion by historians of thirty or more killed, including estimates as high as sixty, are

likely more accurate.

Details that include identities of some dead, and eyewitness accounts never before publicly seen, lead to three conclusions. One is that, on the morning of November 23, 1887, gangs of white regulators performed the tasks of judge, jury and executioner on the streets and in the homes of black Thibodaux residents, killing as many as sixty people. Another is that no official inquiry into the identities of the killers was ever made. 0The third is that the dead can and do speak, if we do our best to listen.

The 2015 murders of nine innocent people at “Mother” Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and the resulting national dialogue resounded even in extreme south Louisiana. A decision by the New Orleans City Council to order statues of Confederate heroes removed as public nuisances intensified debate, and with my editor, Shell Armstrong, a decision was made to present, as contextually as possible, the story of Thibodaux’s bloody secret on the newspaper’s pages. The article was written and drew attention. I was then contacted by The History Press, who asked if I was interested in writing a book on the subject.

I jumped at the chance but was seized by fear of inadequacy. What could I do, I wondered, other than present what had already been reported except in longer form? What new facts could be plumbed other than what I had already discovered over those twenty years of curiosity and frustration?

When the commitment was made, a key appeared to turn in some metaphysical lock. From the archives of Nicholls State University appeared a long-lost list of eight victims, likely far fewer than the actual death toll but enough to allow further investigation. Reviews of census lists and interviews revealed more information, which led to further research. A trail of historical crumbs led to the pension files of Jack Conrad, a former slave and veteran of the U.S. Colored Troops, who was shot and wounded in the massacre.

The Conrad files presented, for the first time, direct accounts of what occurred in Thibodaux, including confirmation of deaths of unarmed people, from the mouths of black people submitted under oath. This was not because the incident itself had been investigated—it never had—but because of an ancillary inquiry into the related matter of Jack Conrad’s injuries.

In 1890, Congress passed a law that allowed Civil War veterans to file for pensions if they could not work, even if their injuries were not related to the war so long as they came about through no fault of the veteran. Coupled with the newspaper accounts, private correspondences of the day and other materials, the Conrad files confirmed the killing and wounding of innocent people on the basis of race in an atmosphere poisoned by concepts of white superiority and panic fed by rumors, as well as a resulting breakdown of law and humanity. There could be no doubt, after all available facts were taken into consideration, that somewhere in Thibodaux exists an as yet unprocessed crime scene.

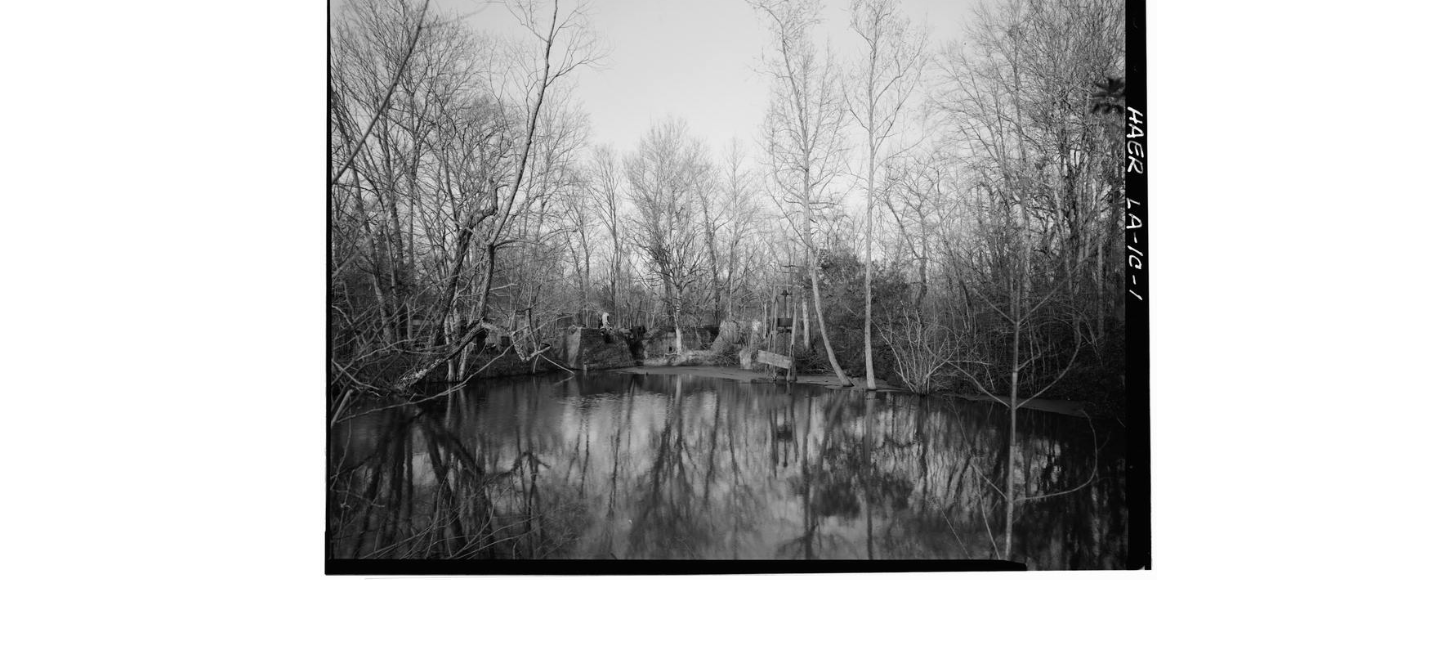

Because of the light Jack Conrad’s files shed on this event, his personal story is interwoven throughout this narrative. He is the living, breathing and talking representative of all those whose voices have, until now, been silenced by the shoveling of dirt on unmarked graves or the unseen decay of earthly remains in swamps and woods.

A number of people asked me while I worked on this project why I would wish to bring up such an event now that it had been laid to rest and relegated to the past.

My reply was and is that reparation for a society’s past sins does not always come in the form of financial compensation but, in a very spiritual sense, by the mere telling of truth, the acknowledgement and baring of uncomfortable fact.

Perhaps now, nearly 130 years after this tragedy occurred, the dead can finally rest, and the living can take comfort that through the telling of truth, some measure of justice has been done.

READ MORE: Civil Rights & Social Justice History