Long before television, and a few years before motion pictures became popular, what did Americans do for entertainment? In the years following the Civil War, the railroad industry took off, connecting great portions of the continental United States. Traveling circuses took full advantage of the advanced network of rails, bringing live entertainment to all corners of the nation. And when the World’s Fair came to Chicago in 1893, millions bought tickets to see the wonders therein. So popular was the World’s Fair, many enterprising hucksters saw potential dollar signs in producing one-of-a-kind events, freak shows, and singular spectacles.

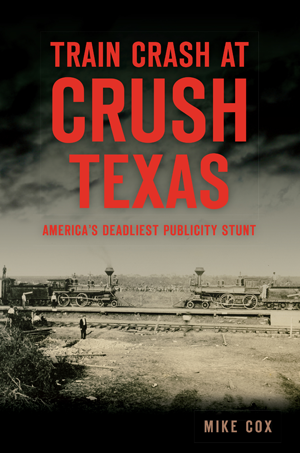

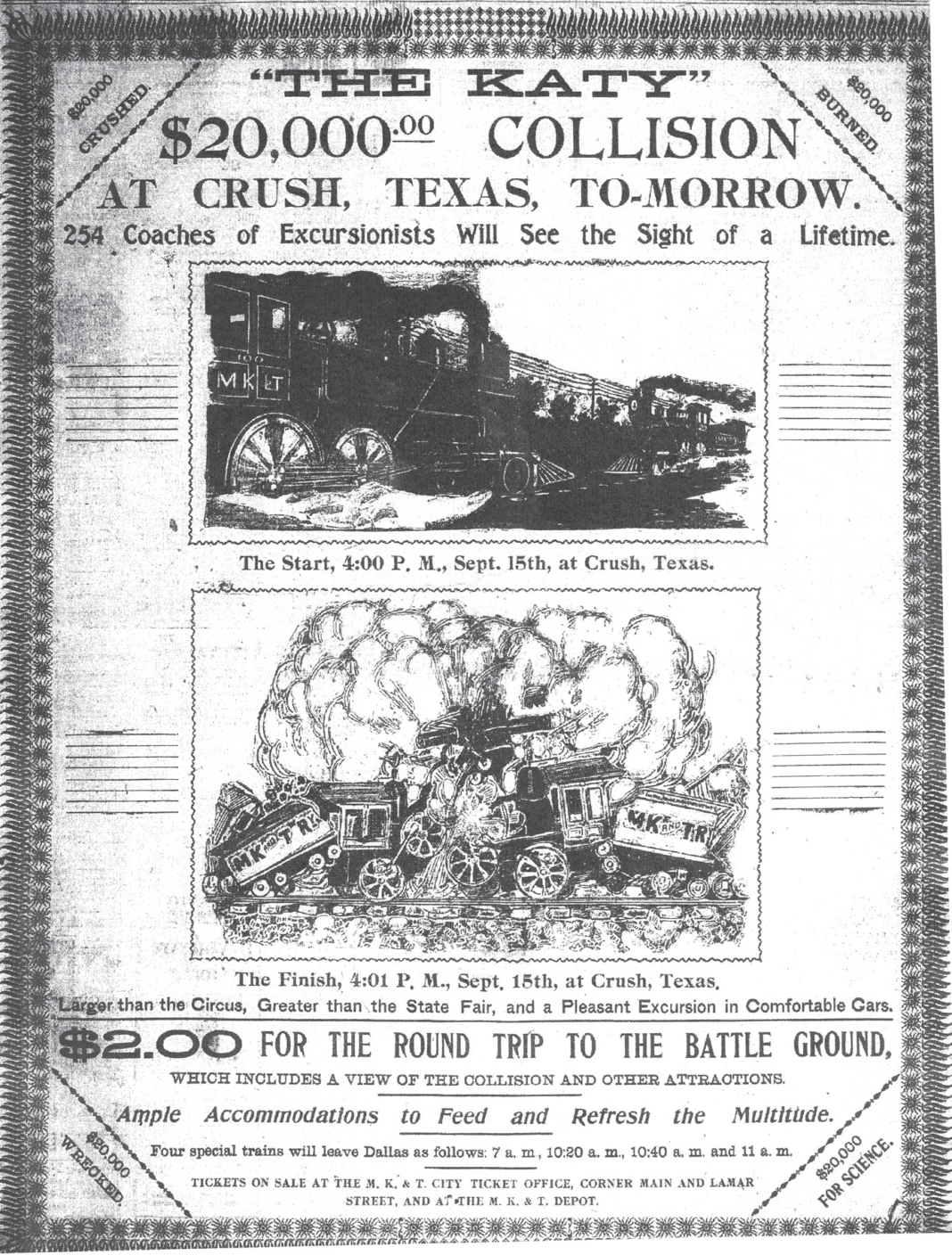

In 1896, up-and-coming executive with the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad William Crush hatched a crazy plan to stage a locomotive collision, promote the hell out of it, and make a ton of money. Crush used the premise of “scientific research” to justify the potentially dangerous venture. The rail line, also known as the M-K-T or the Katy, had seen huge successes in Texas, connecting Galveston and Houston with St. Louis. Why not put on a show for current and future customers?

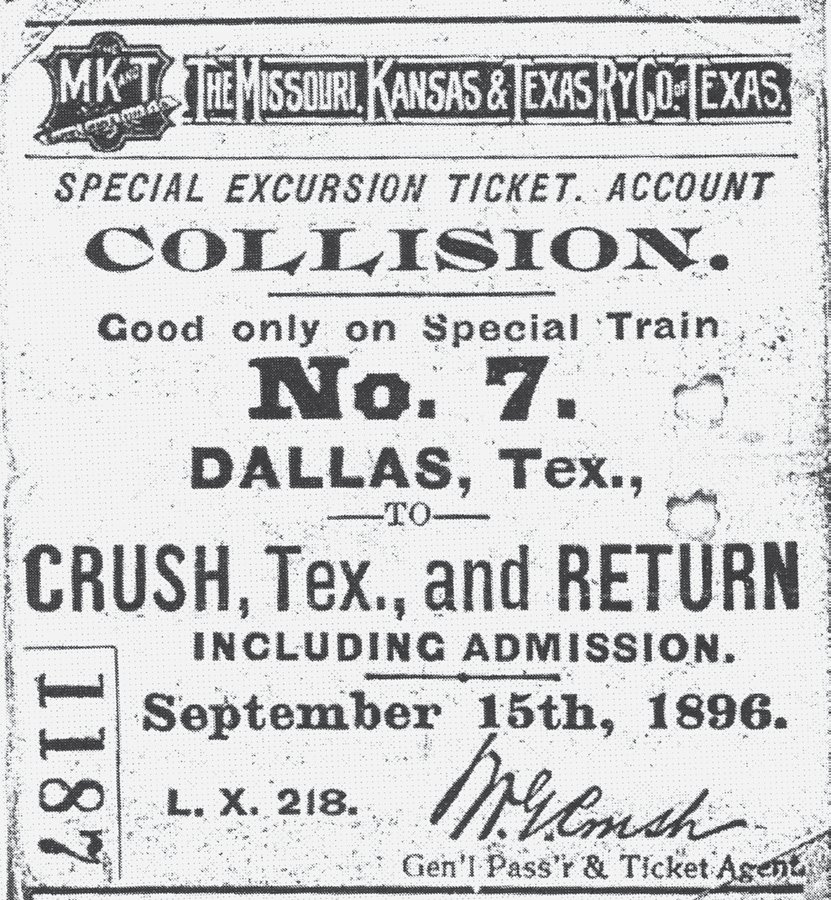

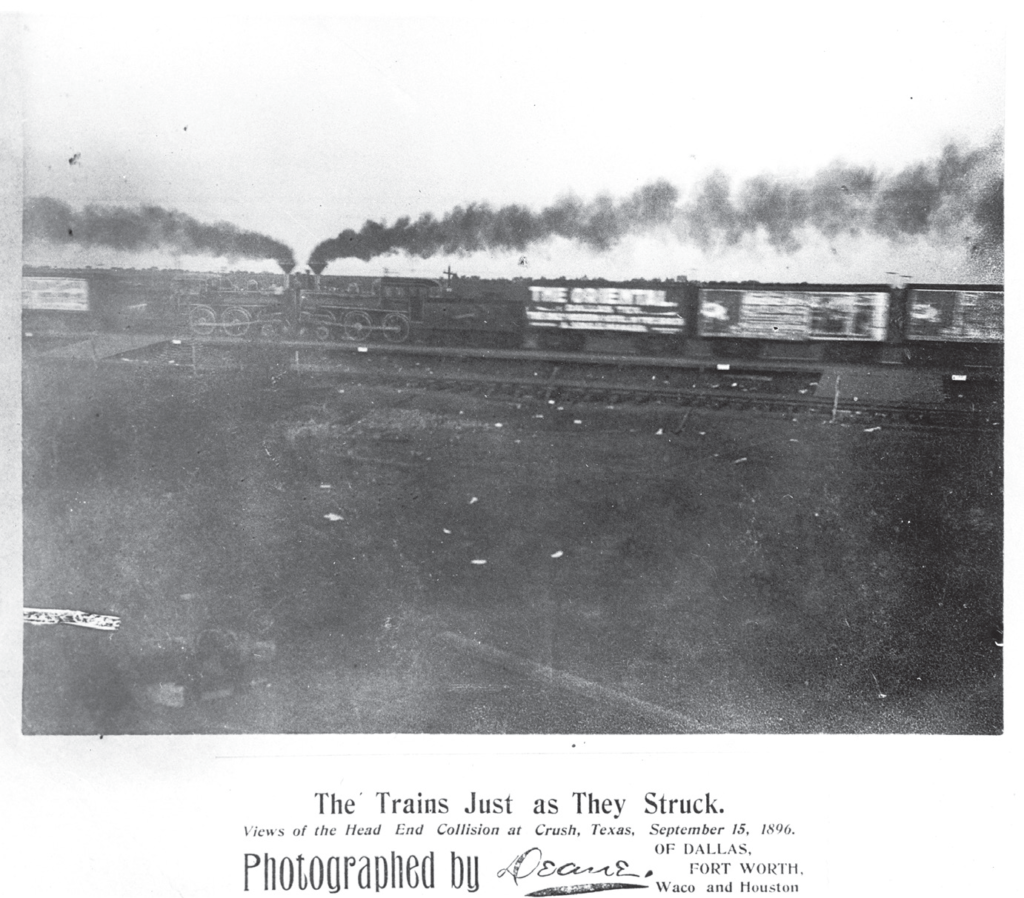

The head-on collision of two obsolete, and unmanned steam locomotives was presented to the public on September 15, 1896 on a stretch of railroad tracks north of Waco. William Crush renamed the town “Crush” probably because “The Crash at Crush” was just too irresistible-sounding (or he couldn’t resit using his own name). 40,000 eager spectators attended — which was free with purchase of a rail ticket.

collection.

When the two speeding locomotives collided, only a few had predicted the results. In addition to a huge smash-up of steel, the boilers on both engines exploded, sending debris hundreds of yards in every direction. Despite safety precautions and buffer zones, three confirmed fatalities were reported. Ironically, one of the official photographers hired that day was hit in the eye with a piece of hurtling train debris.

“It [was] a scene that will haunt a man…make him nervous whenever he hears an engine whistle, and disturb his dreams with black clouds of death-dealing iron hail…”

—Dallas Morning News

Promoter William Crush took full accountability for the catastrophic results, and remained with MKT Railroad for many years. Future Ragtime legend Scott Joplin was entranced by the stunt and wrote “The Great Crush Collision March” to commemorate the mess.

Certainly, common sense and an abundance of sanity prevailed after the Katy Smash-up? Nope. Dozens more locomotive collisions were staged by a multiple of ambitious showmen, with the last one occurring in 1951.