The American Civil War (1861-1865) marked some of the most divisive and devastating years in the country’s history. Afterwards, the country entered what modern historians call Reconstruction. During this time, states in the South were slowly integrated back into the Union while political, economic, and social disparities were addressed to promise the stability of the nation as a whole. Looking back, Reconstruction is seen as a transformative, but challenging era in American history. This is everything you need to know about post-Civil War Reconstruction in America.

The End of the Civil War in America

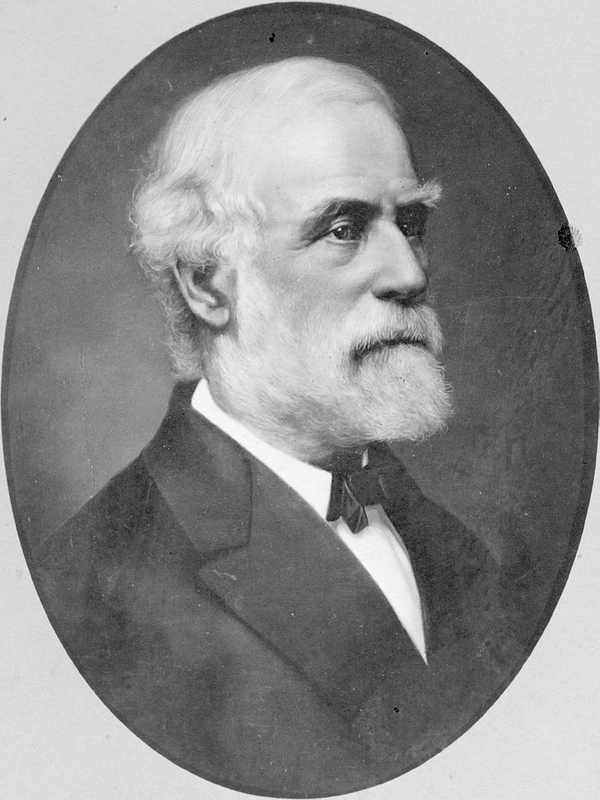

In April 1865, General Robert E. Lee of the South surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant. At the time, Lee hadn’t planned to surrender. Despite the significant losses to the Confederacy in terms of men and supplies, Lee still had some fight left in him. He arrived at the Appomattox County Courthouse to resupply, and found himself surrounded by Grant’s troops. With no other options, Lee was forced to concede.

Slowly, Confederate forts and military leaders began relinquishing their power. Southern President Jefferson Davis was captured along with the rest of his cabinet, thus officially disbanding the government in the South. Confederate headquarters in Florida and South Georgia were handed over to Northern authorities, and the CSS Shenandoah was docked. By early May, 1865, President Andrew Johnson declared the war was “virtually” over, and the country was on its way to repair. However, his official proclamation stating the end of the war wouldn’t come until August 20, 1866.

Setting the Scene for Reconstruction

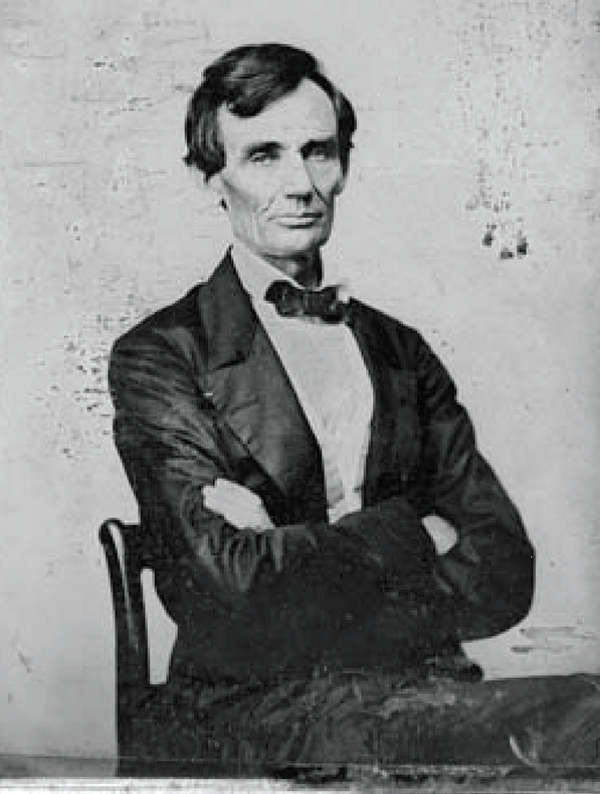

President Abraham Lincoln never named the abolition of slavery as one of his key motivators in the war’s early years. He feared it would tip middle-ground states toward the Confederacy and anger more conservative Northerners. Slavery was forced into the spotlight in 1862, when thousands of freed slaves joined the Union army and marched toward battle, vocalizing their anger with the treatment of African Americans in the South.

At this point, emancipation was at the forefront of the war. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 released roughly 3 million slaves from their owners in the South, and many moved north to enlist with the Union. By the end of the war, the number of former slaves who had become soldiers for the Union had reached upwards of 180,000.

The stakes of the war changed with emancipation on the agenda. Not only would the South be forced back into the Union should they lose the war, but slavery would likely be abolished, thus setting off a massive social shift across the country. Lincoln still had no clear vision for how to successfully reintegrate the South and abolish slavery. During a speech in 1865, he voiced his desire to give all Americans, white and black, the right to vote. Just days later, Lincoln was assassinated, and the aims of Reconstruction would rely on President Andrew Johnson.

Reconstruction: Beginning to End

Johnson understood that Southern states still owned their Constitutional right to govern themselves. He devised a plan that would abolish slavery, reintroduce Southern states into the Union, and still grant these state governments power to redefine themselves as part of America. Johnson decided that the federal government had no place in deciding the voting rules and restrictions enacted in Southern states. Likewise, all the land seized by Union soldiers from slave owners during the war to be given to freed slaves was reverted back to its original ownership. Southern states were required to pay off war debt and abide by the new amendments to the Constitution, but they were given full reign to reconstruct themselves.

The President’s lenient plan allowed freedom for governments in the South to create a set of “black codes.” These were designed to restrict the rights of former slaves in the workforce, and assure they would always land among the lowest-ranking members of society. Elected officials in Northern states and members of Congress responded to these codes by introducing two bills: the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Civil Rights Bills. Their respective purposes were to assist those recently freed from slavery in getting back on their feet in society, and state that all those born in the United States were citizens. Johnson vetoed both bills, causing a major political rift between himself and Congress. The Civil Rights Act became the first law to be passed over a presidential veto, but not long after, in 1868, Johnson was impeached.

Well-off Northerners saw the South in shambles and took advantage of potential economic gain by starting to migrate south. At first they were welcomed, as people in the South recognized their economic hardships could be curbed by investments from wealthy Northerners. Soon, however, their presence became a problem. Southerners considered these “carpetbaggers” as merely seizing an opportunity at the expense of Southern residents still reeling from a devastating war. This was true, but only half of the story. Many Northerners moving south also hoped to help shape these communities in the image of the North. Their goal was solidifying political and social equality for whites and blacks.

Congress took another step to reform the nation with the passage of the Reconstruction Act of 1867. This was again done by bypassing Johnson’s efforts to veto the bill. The act divided the South into five military districts, aimed to systematically help organize the state and local governments. It also required states to ratify the 14th Amendment, which detailed a new definition of citizenship including former slaves and guaranteed “equal protection” for all Americans. In February of 1869, Congress passed the 15th Amendment declaring that no person could be denied the right to vote because of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

By 1870, every state formerly in the Confederacy had been reincorporated into the nation. From 1867 on, African Americans would play a significantly larger role in society, forever altering the landscape of the South. However, many communities began witnessing a stirring of prejudice and racism. Groups like the Klu Klux Klan took shape in major pockets throughout the South, dispersing their message of white supremacy. Throughout the 1870s, President Ulysses S. Grant fought back against the KKK when they tried to interfere with the rights of African Americans. As Reconstruction began to wane and the South regained its stride, the attempts by these groups to set back a progressive anti-racist movement were even more pronounced.

Throughout the Reconstruction Era, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments guaranteed former slaves equal protection as that of their fellow citizens. Congress passed a series of bills that would help reform the nation from its unfair antebellum institutions, and set it on course to modern day. Complete equality would still be years in the future, but Reconstruction marked the beginning of a shifting mindset in Americans.