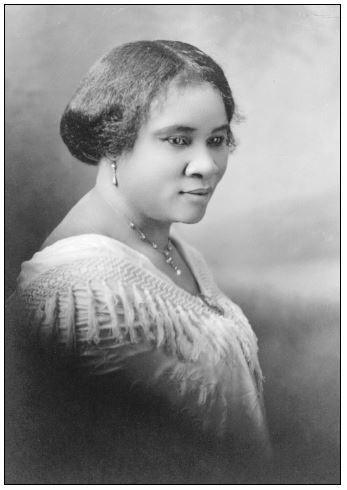

Today, we celebrate the life of the great entrepreneur and philanthropist Madam C.J. Walker (1867 – 1919) who has been described as the first American self-made woman millionaire.

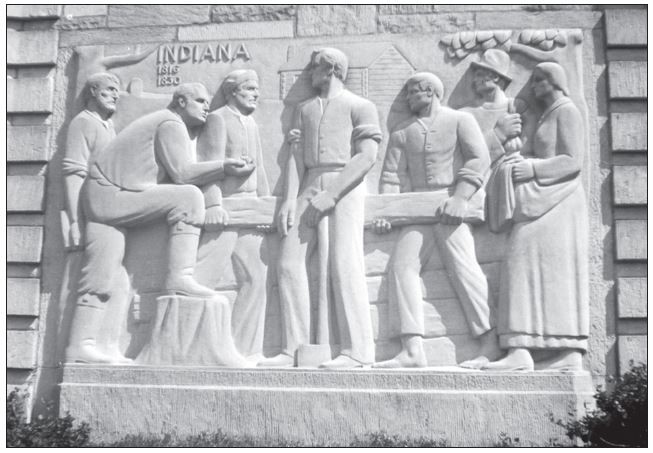

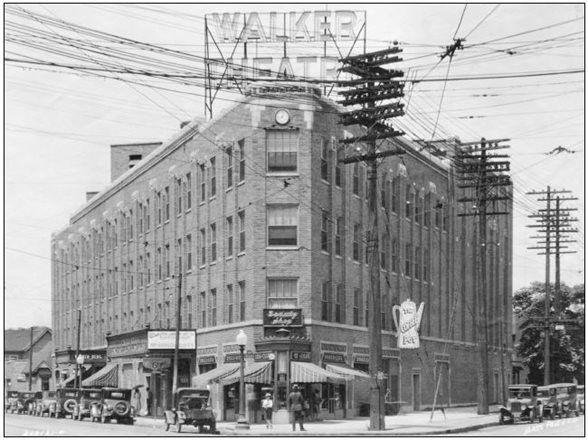

Madam Walker spent her most successful years in Indianapolis, Indiana where she planned a large theater complex that was completed in 1927, eight years after her death.

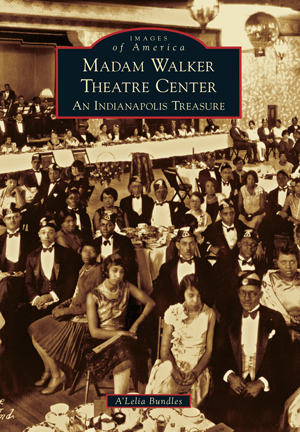

The great-great-granddaughter of Madam Walker, A’Leila Bundles has had a remarkable career in her own right. Bundles is an Emmy award-winning producer and former ABC News Executive and trustee of Columbia University. She has written several books including a highly-regarded biography of Madam Walker “On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker”.

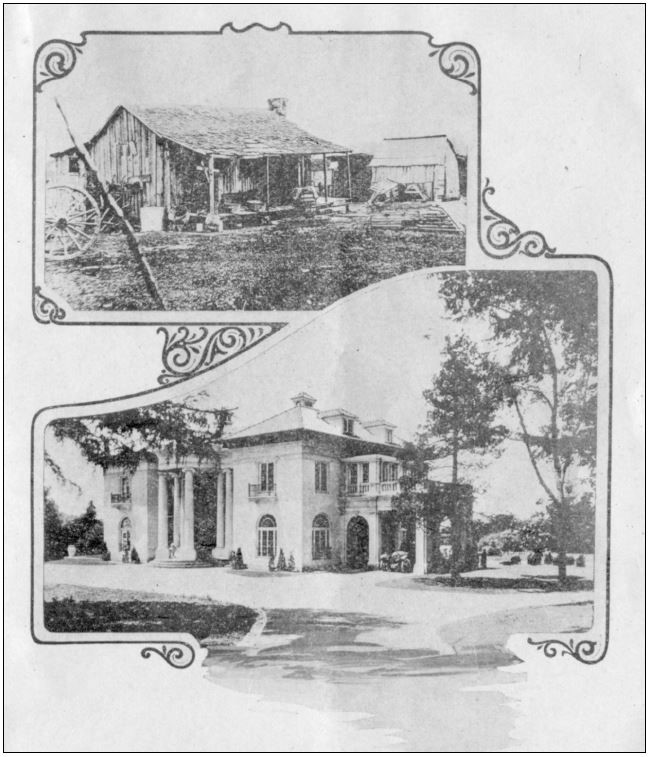

Walker (1867 — 1919) led an inspiring, rags-to-riches life, as captured by the following image showing the circumstances of her birth and the beautiful mansion she built on the Hudson River just a year before her death.

Madame Walker was born Sarah Breedlove in a shack on a Louisiana cotton plantation. She died in a mansion she had built a few miles from the Rockefeller estate that she had named the “Villa Lewato”. It was designed by Vertner Tandy, New York City’s first licensed black architect and was commonly known as a “wonder house”.

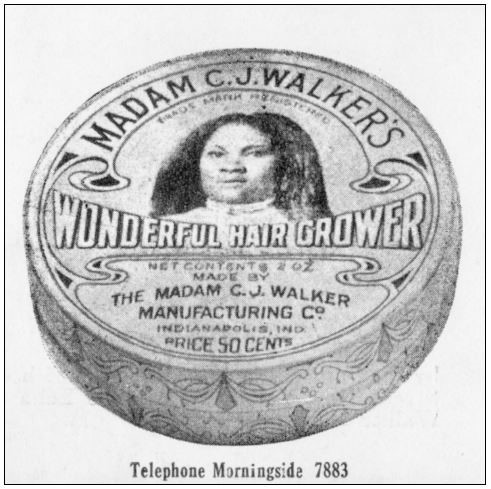

Walker was orphaned at the age of seven and a widow with a child by 20. She supported herself as a laundress in St. Louis for two decades. When Walker became concerned over her hair loss in her late 30s, she discovered and began selling a product for hair restoration which became known as “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower”. With a flair for marketing, investment savvy, and a commitment to hard work, Madam Walker created a large business empire on the foundation of her Wonderful Hair Grower.

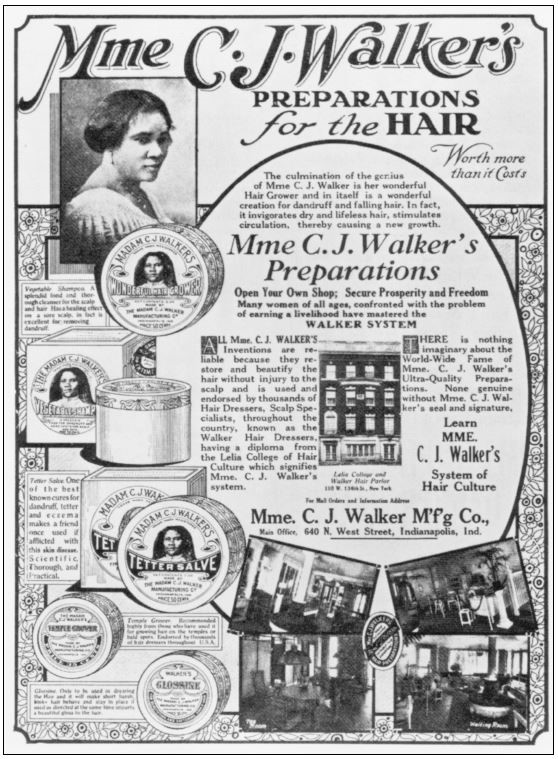

Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower was always her most popular product and was sold in tins featuring her photograph.

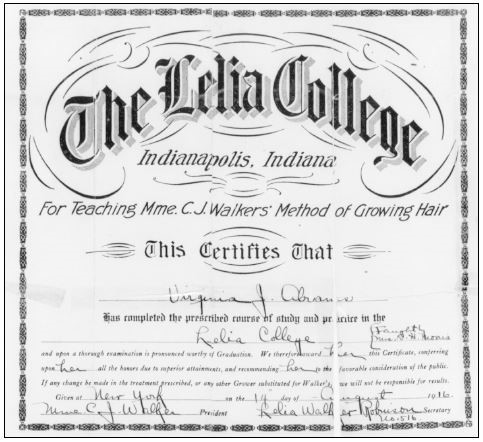

Walker manufactured a line of hair and other cosmetic products for African American women. She franchised her products and created and trained a national sales force. Madam Walker also established a nation-wide system of schools in many American cities to train African American beauticians and cosmetologists. Many women trained in the Walker schools became successful in their own right.

Madam Walker opened her first beautician school in Pittsburgh and named it Lelia College after her daughter.

Madam Walker was a skillful promoter of her products and her beautician schools.

This 1917 advertisement features Madam Walker’s hair preparations, other cosmetic products and her schools. The advertisement exhorts its readers: “Open your own shop. Secure Prosperity and Freedom. Many women of all ages, confronted with the problem of earning a livelihood have mastered the WALKER SYSTEM.”

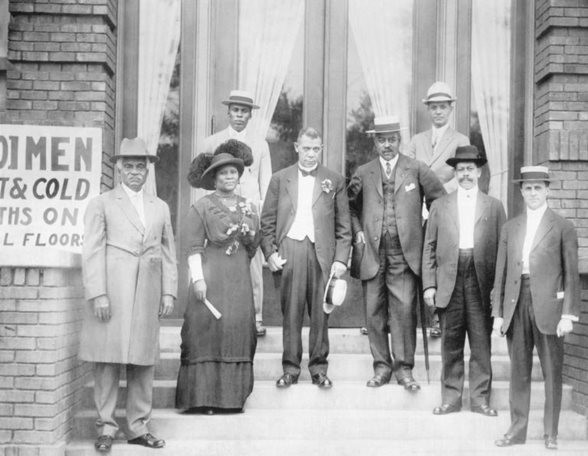

In addition to being a savvy business woman, Madam Walker was also a philanthropist and contributed generously to churches, educational institutions, anti-lynching movements, and other causes devoted to the betterment of African Americans.

In 1913, Madam Walker contributed $1,000 for a YMCA facility in Indianapolis for African American men and boys. In this photograph of the dedication ceremony, Madam Walker is seen with Booker T. Washington and other dignitaries.

In 1914, angered at her treatment by a segregated Indianapolis theatre, Madam Walker purchased a large city block in the city’s African American district to house her company’s headquarters and factory. She dreamed that this facility would become a center of African American cultural life which would free Indianapolis African Americans from indignities. The complex opened just after Christmas in December, 1927 and served for many years as a community landmark and as the headquarters for the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company.

This photograph of the Walker Theatre was taken shortly after its opening in December, 1927. It was a four-story, block long, 48,00 square foot flatiron structure that included the company headquarters, a theatre, meeting rooms, ballroom, businesses, and professional offices.

By the 1970’s, unfortunately, the building had fallen into disrepair and was slated for demolition. However, an inspiring community effort saw the building beautifully restored and reopened in 1988 as the Madam Walker Theatre Center. It has again become a vibrant presence in community life. In 1991, the Walker Building was officially added to the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1998, Madam Walker became the 21st historical figure honored by the U.S. Postal Service in its Black Heritage Series. A’Lelia Bundles, the author of the Images of America book on Madam Walker is fourth from right in this photograph.

This post was written by Robin Friedman for Madam Walker Theatre Center: An Indianapolis Treasure (Arcadia Publishing)