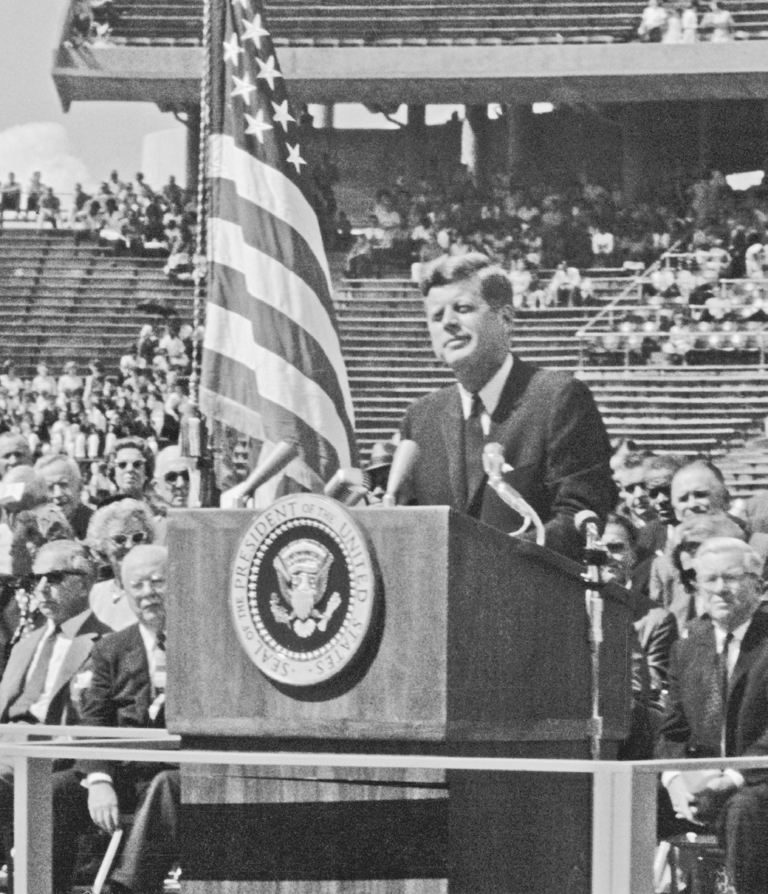

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.”

President John F. Kennedy on September 12, 1962.

President’s Kennedy’s rousing words on that hot Houston day, while not his first moon speech, changed everything for the nation. Just a few months earlier, hundreds had moved to Houston to join a small task force, transforming a sleepy, coastal pasture into the command post for humankind’s greatest adventure. In fact, the team at the newly-dubbed National Air and Space Administration would indeed get humans to the moon by decade’s end.

Manned Space Center

On September 19, 1961, NASA announced that the Manned Space Center would be built on more than a thousand acres, 20 miles southeast of downtown Houston. The site grew rapidly in the early 1960s with buildings and personnel, along with engineers and scientists, and of course, astronauts. Houston immediately embraced its new neighbors and celebrated that they were now known as Space City.

The Moon

“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Apollo 11

In 1969, only eight years after Kennedy’s speech, Apollo 11 made the historic first lunar landing meeting the president’s goal. Astronauts left behind a plaque declaring, “We came in peace for all mankind.” On July 24, the Apollo 11 crew returned safely to Earth. Celebrating this momentous achievement with the rest of humankind were the flight controllers in the Mission Operations Control Room.

Johnson Space Center

In August 1973, on what would have been former President Lyndon B. Johnson’s 65th birthday, his widow, Lady Bird Johnson, and her family joined NASA officials to dedicate the center in honor of the late president, a longtime champion of NASA. The year prior, President Richard Nixon approved the Space Shuttle program. The mighty minds at the JSC would be responsible for designing, developing, and testing the reusable orbiters for decades.

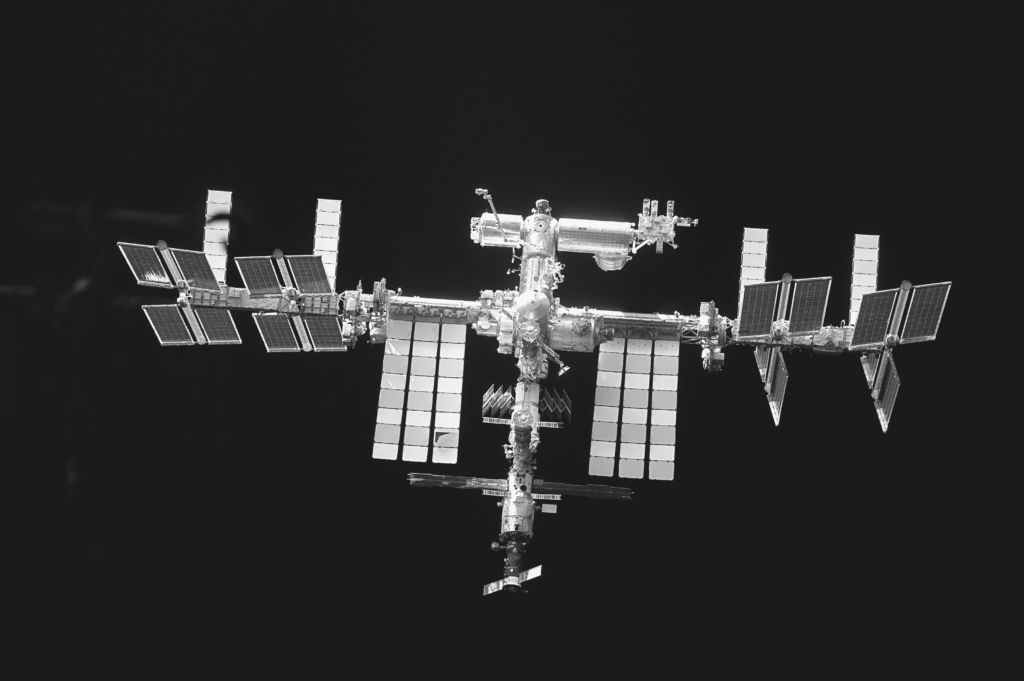

The Next Frontier

The final shuttle mission landed in 2011, when Atlantis touched down in Florida. The International Space Station, constructed from 1998 to 2011, supplied by the shuttle program and the aid of other nations, with 161 spacewalks and a combined 1,021 work-hours, opened on November 2, 2000. The Johnson Space Center manages ISS operations, and coordinates five space agencies representing 15 nations. To this day, astronauts are still trained at the Johnson Space Center, and space remains an important part of Houston’s identity.