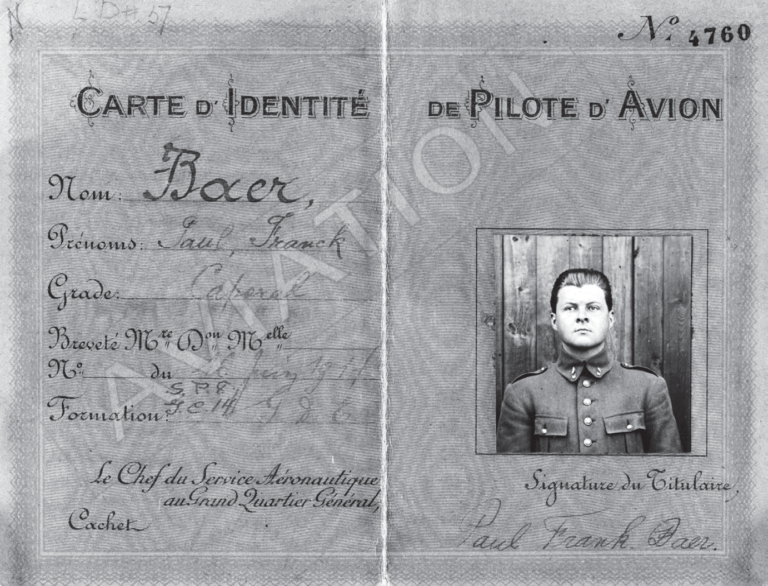

Hoosier native Paul Baer was a pilot of many firsts, eventually becoming a famous aviator and the American military’s first flying ace.

Born into a modest midwestern family in the late 1800s, Baer grew up short and shy in Fort Wayne in the late 1800s. But he wasn’t short on ambition. During World War I, Baer volunteered to join a new breed of combatant: the fighter pilot dogfighting in the skies over France. Indiana has produced many important war figures. But Baer earned a giant reputation as the first-ever American to shoot down an enemy plane — a thrilling story that no one has told better than Baer himself.

Starting out with the Spad

In France, Baer served first as a volunteer in the French military, before switching to an American squadron once his country joined the conflict. He flew French planes built by the Société Pour Aviation et ses Derives, or SPAD. The abbreviation became the name of a sturdy fighter, with more than 5,600 Spad fighters being built during World War I for France, Great Britain and other countries. In a letter to a friend, Baer noted, “we fly Spads of two types, the 180 h.p. and the 220 h.p. The 220 carries two of the Vickers machine guns, but the motors do not hold up very good. . . . You can never depend on them. We therefore prefer the 180s. It carries only one machine gun.”

Baer’s First Kill

Baer achieved his first victory on March 11, 1918, shooting down a German Albatross fighter near Rheims. Two days later, Baer recounted the episode in a letter to his father:

Dear Dad:

If I remember right, today is your birthday. I will write you a letter. . . . Well, Dad, at last I got my first “official” German aeroplane. Day before yesterday, I, unaccompanied, was flying inside the German lines. As time drew near for me to come home, as I had been out my full time, and while almost at our lines, the French send up a signal to me which told me in what sector the Boche were. I turned around and was greeted by seven German planes. Part of the enemy machines were above me and part of them below. Well, I only had enough gasoline for ten minutes more flight, and I was six or eight kilometers inside their lines. I pointed my machine at the closest one to me, and as soon as I got right on him, I opened up with my machine gun and down he went. The rest of them came at me at the same time and I sure did some “scientific retreating.” Well, the Hun I killed is official, that is I got credit for killing him. He fell about seven kilometers in his own lines, but the French saw him hit the ground.

The Hometown Response

It was the first victory for a pilot flying in the American military. Back in Indiana, an Associated Press reporter described the reaction of Baer’s sister, Mabel, upon hearing the news: “Mother will be so proud of him when she hears,” Mabel said. “She’s here in Fort Wayne now but there’s no telephone where she is on Fox avenue, but I’m going to find her right away to tell her what Paul did. He was in Paris the last word we had from him. You’re real sure he wasn’t hurt at all?”

Baer was fine. In fact, he tallied further victories on March 16, April 6 and April 12. On April 23, 1918, he shot down his fifth Hun plane, making the Hoosier pilot the first American ever to become a combat ace.