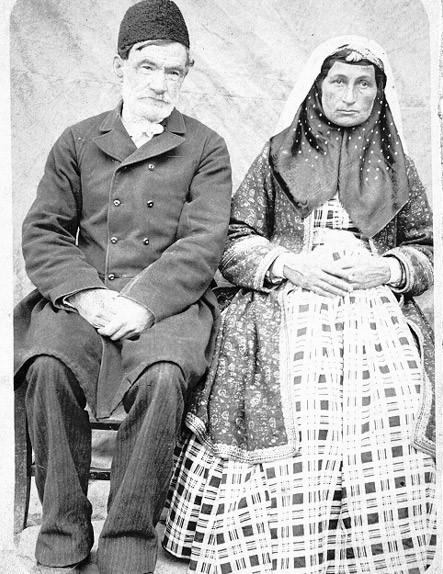

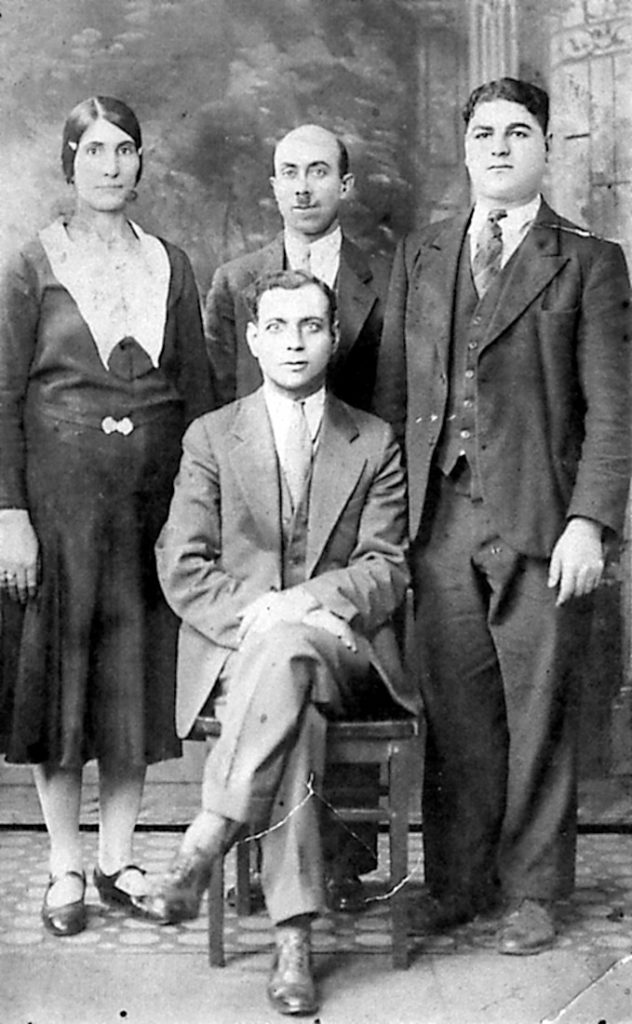

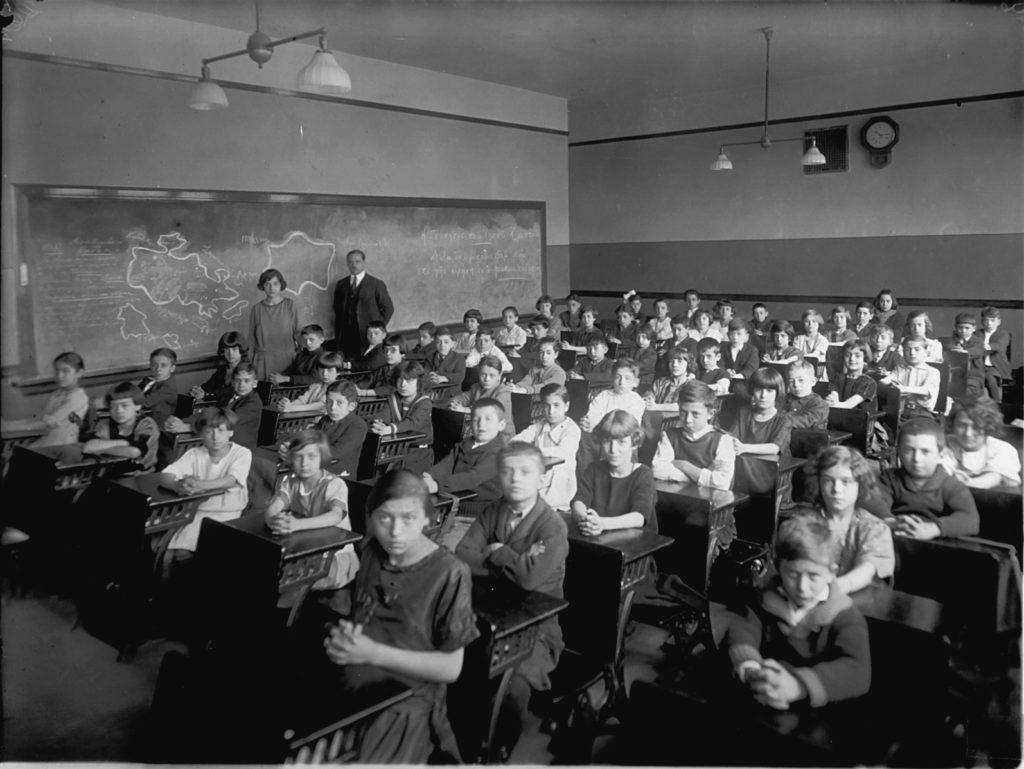

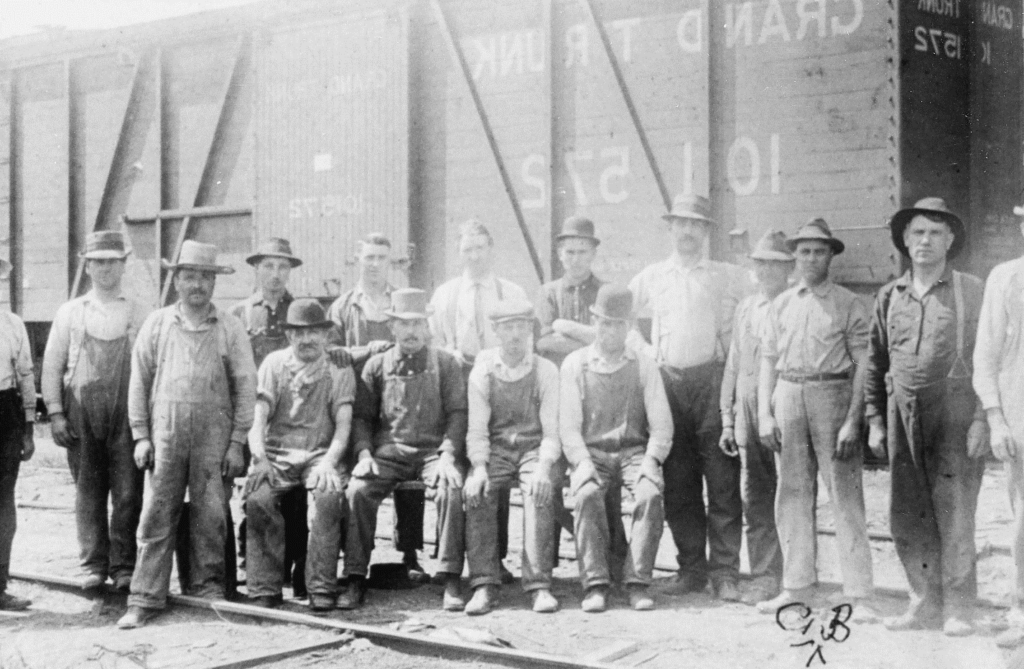

Young paesani from the Marche region pose in Chicago Heights for this 1920s photograph. Photographs like this, implying success and contentment, were sent back to Italy and often sparked the desire of friends and family in Italy to move to America.

Migration

Five million Italian immigrants came to the United States before 1914. Some of them were birds of passage, here to work a season or two, and then return to Italy. Many started on railroad jobs and were drawn to settle in their railroad’s winter headquarters—Chicago. Others were attracted to Chicago by the favorable labor market in one of the fastest-growing industrial cities in the world. Chains of migration linked Chicago with towns in northern and southern Italy.

Learn More: Italians in Chicago by Dominic Candeloro

Some of the towns which contributed migrants to Chicago were the following: Alta Villa Milicia, Tesche Conca, Caccamo, Lucca, Ponte Buggianese, Pievepeligo, Sant’Ana Peligo, Mola di Bari, Amaseno, San Benedetto del Tronto, Castel di Sangro, Cosenza, Castel San Vincenzo, and scores of others. Though we often minimize the emotional cost of emigration when we recount three-generation success stories, separations caused by emigration hurt deeply. Even the considerable financial remittances sent back to Italy by the new immigrants could not erase that pain.

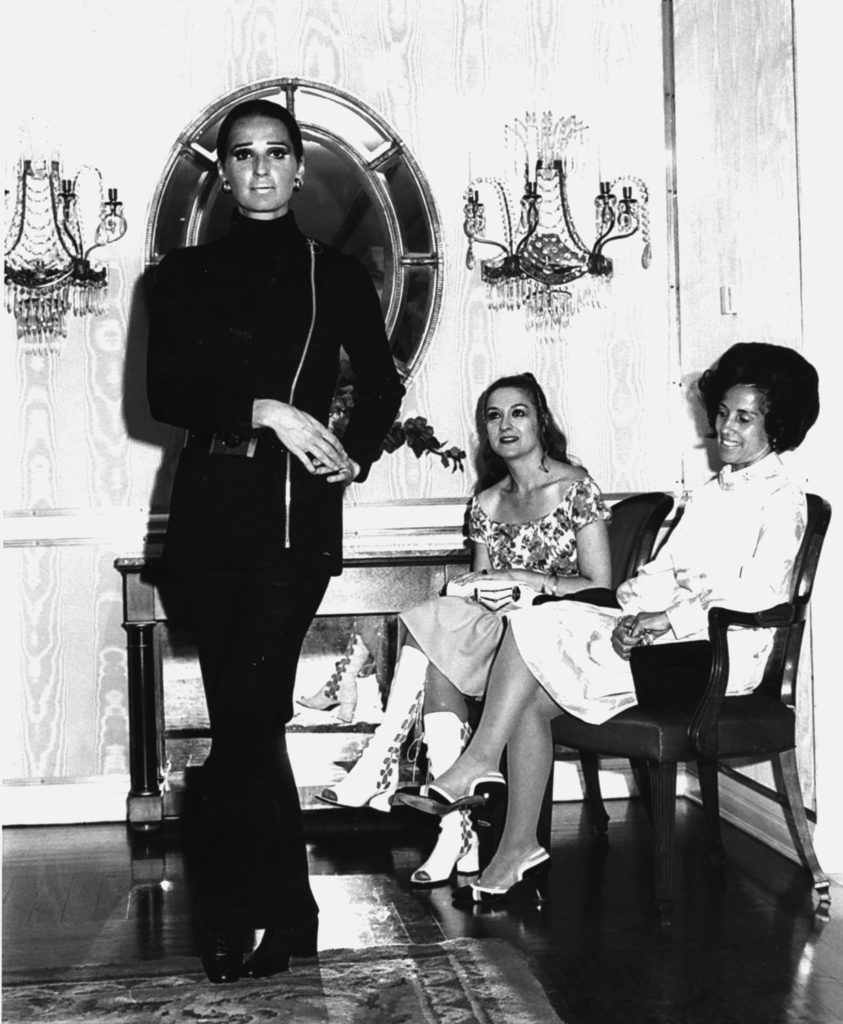

Related Reading: Italian-American Women of Chicagoland by the Italian-American Women’s Club

Family

For the early immigrants, family was everything. They left the family in Italy in order to save it. In Italian culture, the family is a social institution much stronger than the Church, the schools, or the government. They under consumed and saved up money in order to create chains of migration that brought brides, mothers, cousins, and all matter of kin to join them in America. Family solidarity was a key reason why Italian immigrants in Chicago were able to thrive.

Work

Buy the Book: Italians in Chicago by Dominic Candeloro

Italian immigrants came to America ready and willing to work. “Pane e lavoro” (bread and work) was their goal. In comparison with conditions in the Old Country, opportunities to work in Chicago were terrific. Though a large number of the immigrants were illiterate in their own language, they possessed agrarian, handyman, and household skills that served them well in their new country. The immigrants worked hard for themselves and their families. No job was too humble and no one ever refused overtime because it ultimately helped support the family. Working conditions were horrible and industrial accidents, frequent. Many in the first and second generations literally sacrificed themselves in backbreaking jobs on construction, in the factories, and at home so that their children could have a better life.

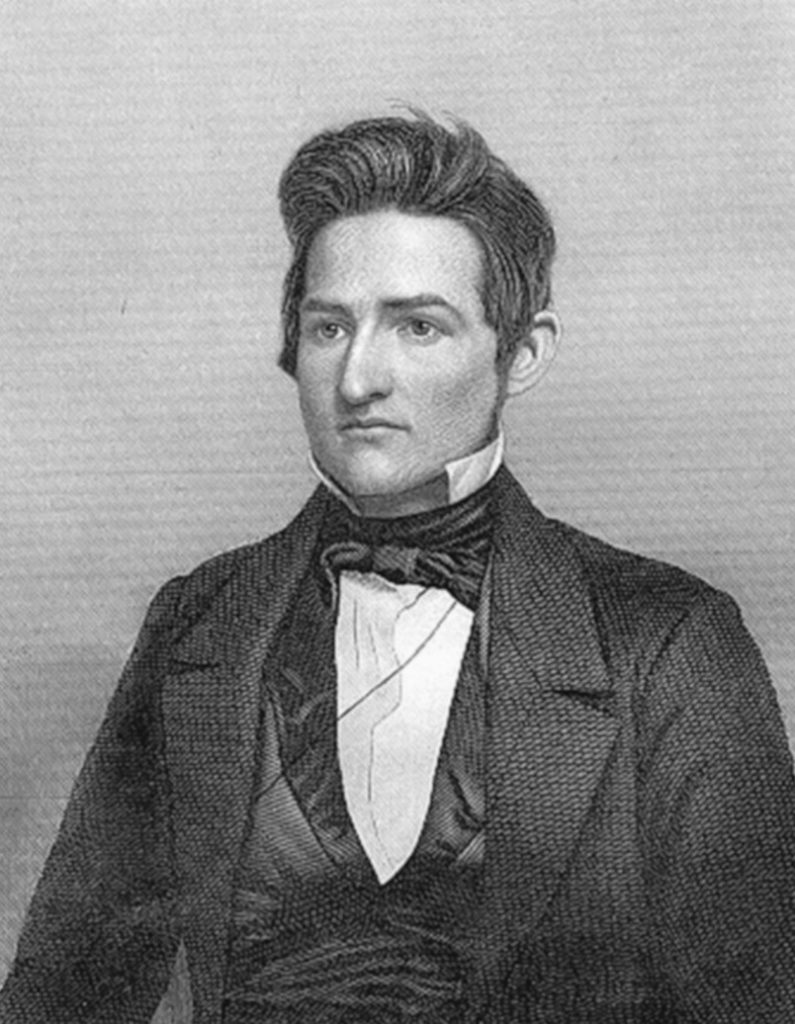

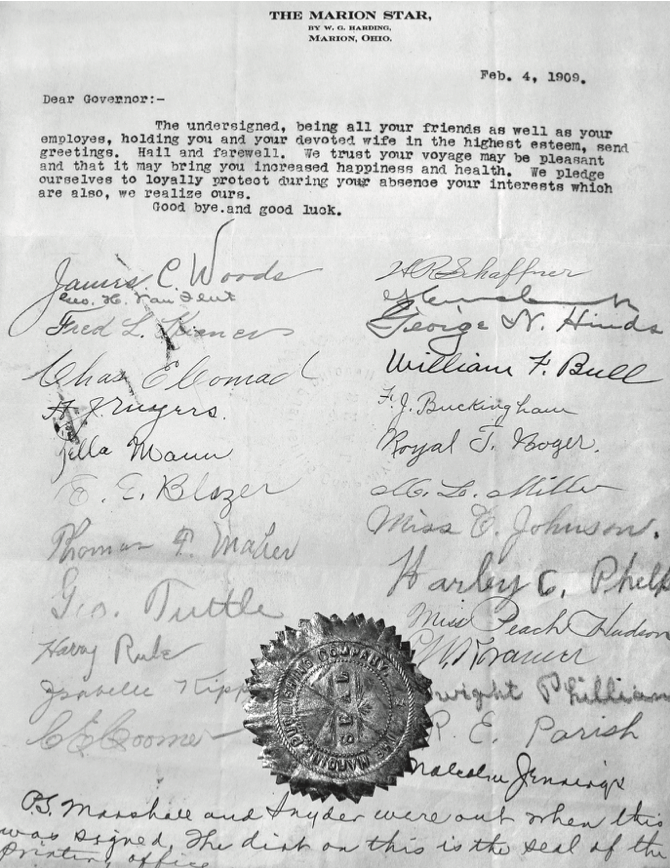

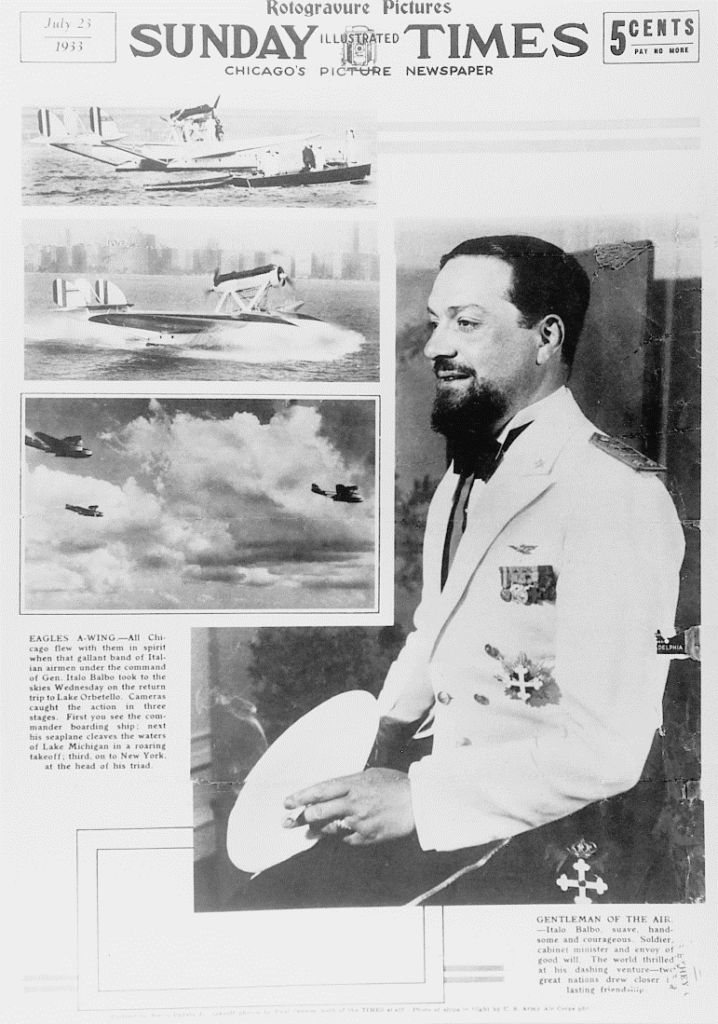

Balbo’s Flight

The Sunday July 23, 1933 Times rotogravure section paid tribute to the departure of the gallant Italo Balbo. The avalanche of positive press that accompanied the Balbo flight was in stark contrast to the steady stream of gangster news stories that besmirched the image of Italian Americans in the city of Al Capone.

The Chicago newspapers in the 1930s rarely had a good word to say about Italians until Italo Balbo came on the scene with his transatlantic squadron. The pioneer aviator guided his squadron of 24 seaplanes from Italy to Chicago in a grand gesture that captured the imagination of the American public. Tradition has it that every Italian in town who could possibly get away went down to the Century of Progress Fair to greet Balbo and celebrate.

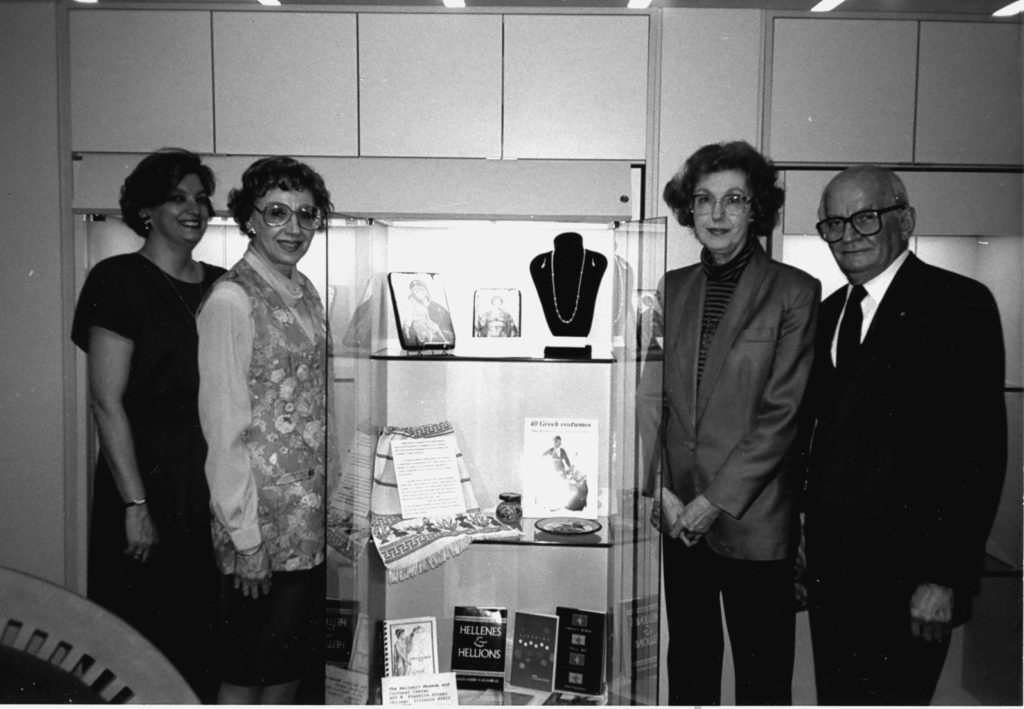

Preserving the Culture

Historian Oscar Handlin has stressed that the migration process “uprooted” immigrants and robbed them of their culture. Since Columbus Day was made a national holiday (in large part, through the efforts of Chicago Congressman Frank Annunzio), it has become a focal point for the celebration of Italian-American culture. Enjoying less public notice than Columbus Day are the dozens of organizations like the Italian Cultural Center, Casa Italia, academic, folk, regional, educational, and artistic groups and individuals dedicating themselves, 100 years after migration, to the maintenance and promotion of Italian-American culture.

To learn more about the Italian community in Chicago, click here.