The author of three books from The History Press, Rosa Walston Latimer was inspired by the story of her Harvey Girl grandmother to preserve women’s history. The New Mexico Magazine described Latimer’s writing as “paying devoted attention to the vibrant inner lives and daily work life of Harvey Girls, transforming what could have been a prim volume into an intimate page-turner.”

When the railroad forged its way west, Fred Harvey established restaurants and hotels along the Santa Fe tracks. Certainly Mr. Harvey had a unique vision and was an astute businessman; however, it was the Harvey employees, led by waitresses dressed in starched black and white uniforms, known as Harvey Girls, who made the Fred Harvey company a success. Beginning with the first eating establishment in Topeka, Kansas in 1876 and lasting until the mid-1940s over 100,000 women followed the Santa Fe Tracks west to work as Harvey Girls. However, these adventurous women were much more than welcome faces for weary travelers.

As Harvey Houses were established in small railroad towns, it proved very difficult to find employees among the locals who could meet the high standards of service required by Fred Harvey. Using classified ads in popular women’s magazines and newspapers in the Midwest and Northeast, Mr. Harvey enticed qualified young women to apply for jobs as waitresses in the far-flung Harvey Houses.

Following a personal interview in the Kansas City office, Fred Harvey handpicked young women, dressed them in proper, starched uniforms and sent them out to feed the traveling public. These Harvey Girls would change the course of women’s history. Many were the first to venture more than walking distance of their hometown. Most were the first women in their family to work—to take on a role other than wife and mother. Harvey Girls earned good wages – as much as twenty-five dollars a month plus room and board – for the first time allowing them to save for an even brighter future or send money home to help a family struggling through the Depression.

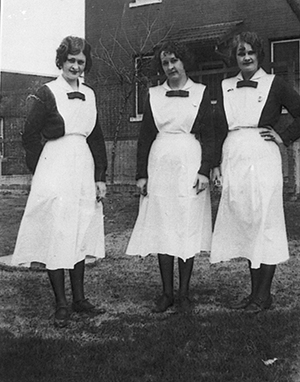

Harvey Girls brought their eastern and midwestern sensibilities to a job that previously had not been held in high esteem. Harvey’s strict rules about dressing modestly, wearing little or no makeup and conducting oneself in a respectable manner served the purpose of reassuring the young ladies they would be in good company, working and living with likeminded women. Their reputations would be protected even far from home, where they would be judged without benefit of a family’s good reputation.

At the time early Harvey Girls were hired, workingwomen were often scorned unless they were teachers or nurses. Waitressing in particular was considered one of the lowest professions a woman could choose and was certainly not thought of as a proper profession for a white, middle-class young woman. In the unsettled West, many waitresses were also prostitutes, and even when this was not true, the perception prevailed. Usually tough, coarse women were the only ones who could make it alone in remote, rural areas. The sheltered living circumstances provided for Harvey Girls made it possible for more refined women to survive in uncivilized, developing railroad towns. Harvey Girls were expected to conduct themselves in a ladylike manner at all times. This conduct changed the public perception of working, single women, especially waitresses.

Fred Harvey’s story is a great success story. The story of Harvey Girls is an important, parallel success story and a vital part of women’s history in our country. The culture and sensitivity of the iconic Harvey Girls who “fed the trains” surely helped civilize the wild, unsettled West.