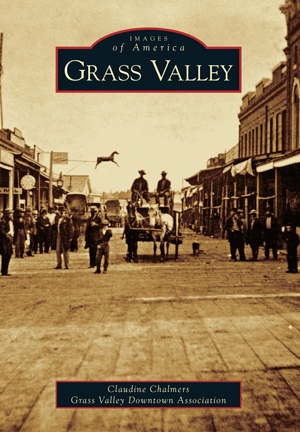

One of the greatest things about American communities is that they create and foster a surprising amount of diversity. Take, for instance, the rough and tumble pioneer community captured in Claudine Chalmers’ Grass Valley. A combination of rare images of the Grass Valley, California community and Chalmers’ own commentary and discussion, Grass Valley shows how much there is to be learned from studying local communities.

Chalmers, a PhD in History, was born in France and later fell in love with California’s gold country after immigrating to northern California. Her book starts by describing the early Native American inhabitants of Grass Valley before it became the site of the second California Gold Rush. The indigenous population, known as the Nisenan, were driven off by the influx of miners and farmers. They were later displaced as a result of this influx to small reservations.

In Grass Valley’s early years during the second California Gold Rush, settlers came individually and dug “coyote holes” to try to extract gold from quartz rock. This was a risky and hazardous, if lucrative occupation. With the arrival of these pioneers, however, began the rudiments of a town.

These early techniques of mining gold soon gave way to larger, more sophisticated methods that required infusions of capital from large corporations. However, these early immigrants helped to instill the developing community with diversity. The Grass Valley community soon prospered through its gold and other mineral wealth, becoming home to large influxes of immigrants. And in 1855 for example, two immigrants seeking a better life had a child in rugged Grass Valley, California, whom they named Josiah Royce. While one might not expect a Wild West mining community to produce one of America’s great philosophers, that is exactly what Grass Valley did.

Royce, who lived from 1855 to 1916, eventually went on to teach at Harvard University for over thirty years after spending his formative years in Grass Valley. He also wrote several important books (including a history of early California), and was a friend and colleague to philosopher William James. One of Royce’s main philosophical interests was in the “Idea of the Community,” and he remarked near the end of his life that his upbringing had helped to spark and fuel this interest, saying

“The wide prospects when one looked across the Sacramento valley were impressive, and had long interested the people of whose love for my country I had heard much. What was there then in this place that ought to be called new, or for that matter, crude? I wondered, and gradually came to feel that part of my life’s business was to find out what all this wonder meant… I strongly feel [now] that my deepest motives and problems have centered around the Idea of the Community, although this idea has only come gradually to my clear consciousness. This was what I was intensely feeling, in the days when my sisters and I looked across the Sacramento Valley and wondered about the great world beyond our mountains.”

The community that Royce saw in Grass Valley flourished during his childhood. A local government was soon established; supporting business (including the ubiquitous taverns) grew, and schools, churches, parks, and newspapers helped to create a sense of community life.

This is not to say that Grass Valley didn’t face some challenges. In its early years, the community went through many transformations, including surviving two large fires. After rebuilding following these fires, a narrow gauge railroad was soon built, primarily to bring the gold mined in the town to market. Streets were paved, and a street car system provided transportation before the advent of the automobile at the turn of the 20th century. Still, the community managed to make room for all, with many ethnic groups calling Grass Valley home.

By 1900, Grass Valley still relied on the gold market to drive the city’s economy. However, community projects remained at the center of the town’s culture, and in 1916 the Grass Valley public library was built with funds procured from a Carnegie grant. The library, located at 207 Mill Street, was built on the same site where Josiah Royce had been born nearly 61 years before. Royce, who at that point lived in Cambridge due to his teaching obligations at Harvard, subsequently died that same year.

The gold market would continue to fuel Grass Valley’s economy until World War II, when the war forced the closure of the gold mines, and thereby ended the narrow gauge railroad. The city then entered a decline, where it seemed the community that Royce had grown up within might finally be played out. Beginning in the 1960s however, the Grass Valley Downtown Association and the City of Grass Valley began working together to help reinvent the city as a retail center. The city also focuses on its historic past as a mining town of the Gold Rush and its more notable residents. This focus led the city to rename the library (now on the National Register of Historic Places) for Josiah Royce in 2005.

While the early days of Grass Valley’s rough and tumble gold mining are long past, the community built around that historic heritage has not waned even in the face of difficulties like fire, war, or the end of the gold trade. Today, Grass Valley properly keeps alive its history and sense of self as a community while continuing to move forward, revealing that there is much we can learn from Royce and his home, and about the true meaning of a community.