Emancipation Deferred

Although President Abraham Lincoln had issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862 (after the Battle of Antietam), and the final proclamation on January 1, 1863 (the same day as the Battle of Galveston), they actually had a minimal immediate impact on the lives of most of the millions of the nation’s enslaved African Americans, especially the slaves in Texas. The proclamations did have a significant effect on the prosecution of the Civil War, on the political landscape and in the international community, but it was only with battlefield victories— many of them hard-fought and won by ex-slaves in uniform—that the proclamations could be enforced. Granger’s order, then, was very important in that it legally abolished slavery in Texas forever.

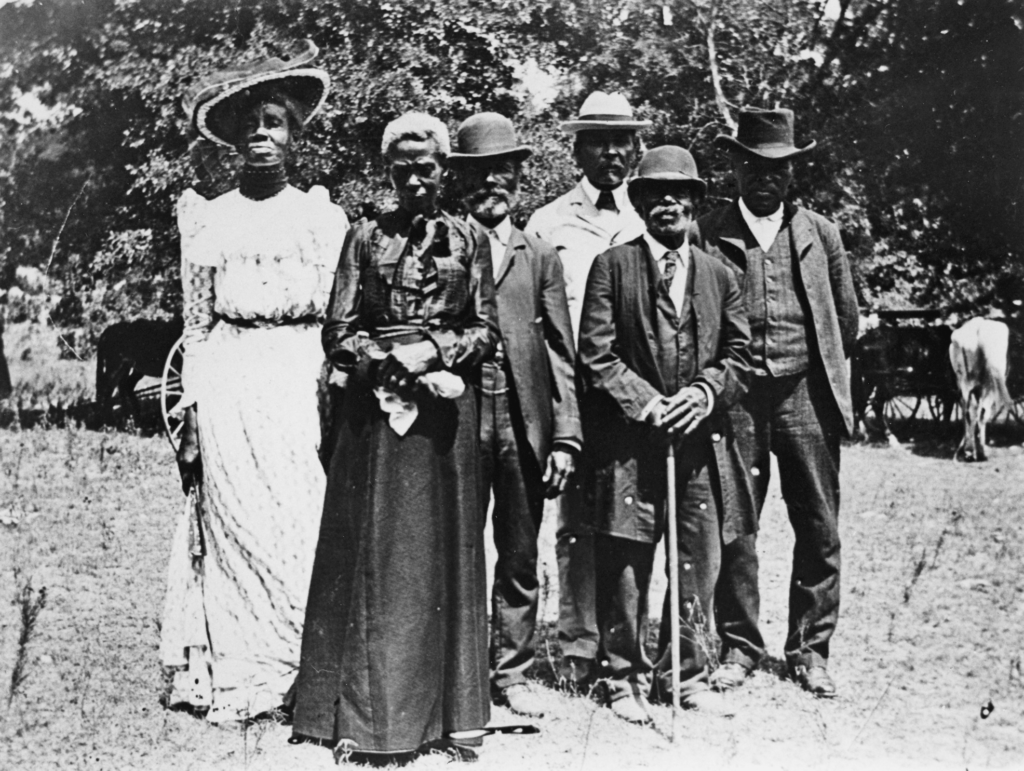

Austin Juneteenth Celebration, 1900

This band played at the Austin 1900 Juneteenth celebration.

Local tradition has it that on June 19, 1865—three years after the President’s Proclamation–General Granger read his order and the Emancipation Proclamation from the balcony of the home of James M. in Galveston. Other historians have suggested the order may have been issued from Granger’s headquarters on the Strand or from the United States Customhouse. Where or whether the order was read aloud, it was posted throughout Galveston and printed in newspapers in the city and throughout the state. In postwar interviews, slaves throughout Texas remembered masters calling them together to read Granger’s order and learning they were now free.

The announcement was originally known as General Order Number 3:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Read More: “The Enduring Legacy of Juneteenth: Life After Emancipation”

It took time—weeks or months sometimes—for the news to reach slaves on plantations in the inland frontier. As Henry Louis Gates described in a PBS article, “When Texas fell and Granger dispatched his now famous order No. 3, it wasn’t exactly instant magic for most of the Lone Star State’s 250,000 slaves. On plantations, masters had to decide when and how to announce the news — or wait for a government agent to arrive — and it was not uncommon for them to delay until after the harvest. Even in Galveston city, the ex-Confederate mayor flouted the Army by forcing the freed people back to work.“

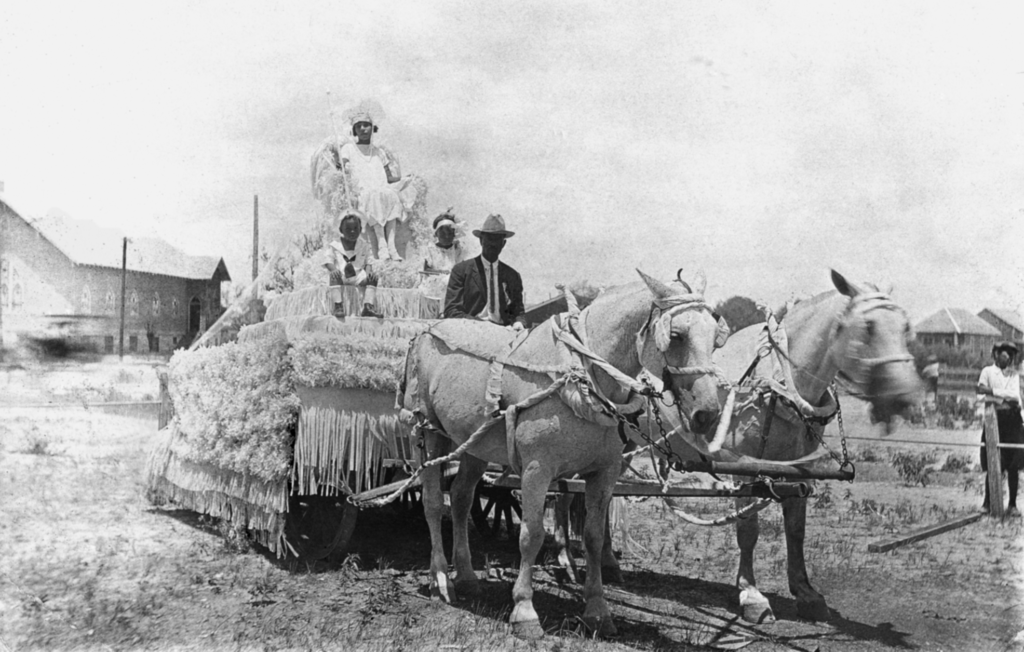

Gloriously commemorating Juneteenth, Anita Blanch Mays and her royal attendants ruled this annual celebration one summer in the 1920s. Riding in the parade with Queen Anita are Dorothy Kitchen Vaughn (right) and her brother L.C. Kitchen, the children of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Kitchen. The driver is unidentified. (Courtesy of the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History, Alclair Pleasant Collection.)

Still, it would take time for that freedom and equality to be fully realized. Even Granger’s order was “stated in a patronizing tone,” as one historian declared, requiring the freedmen to find work and forbidding idleness.

The day has been remembered ever since as “Juneteenth” (a portmanteau of the words “June” and “nineteenth,” also called “Emancipation Day” or “Freedom Day”). Beginning in 1866, African Americans in Galveston and throughout the state began annual celebrations of Juneteenth with church services, parades, readings of the Emancipation Proclamation and more.

Jesse Jackson and state legislator Al Edwards, who sponsored the bill to make Juneteenth a state holiday, wave to a crowd of more than 2,000 University of Texas at El Paso students on February 15, 1971. Jackson urged the crowd to form a Rainbow Coalition of blacks and Hispanics to vote for the Democratic ticket. (Courtesy of the El Paso Herald Post.)

More: Virtual tour of related exhibits at the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

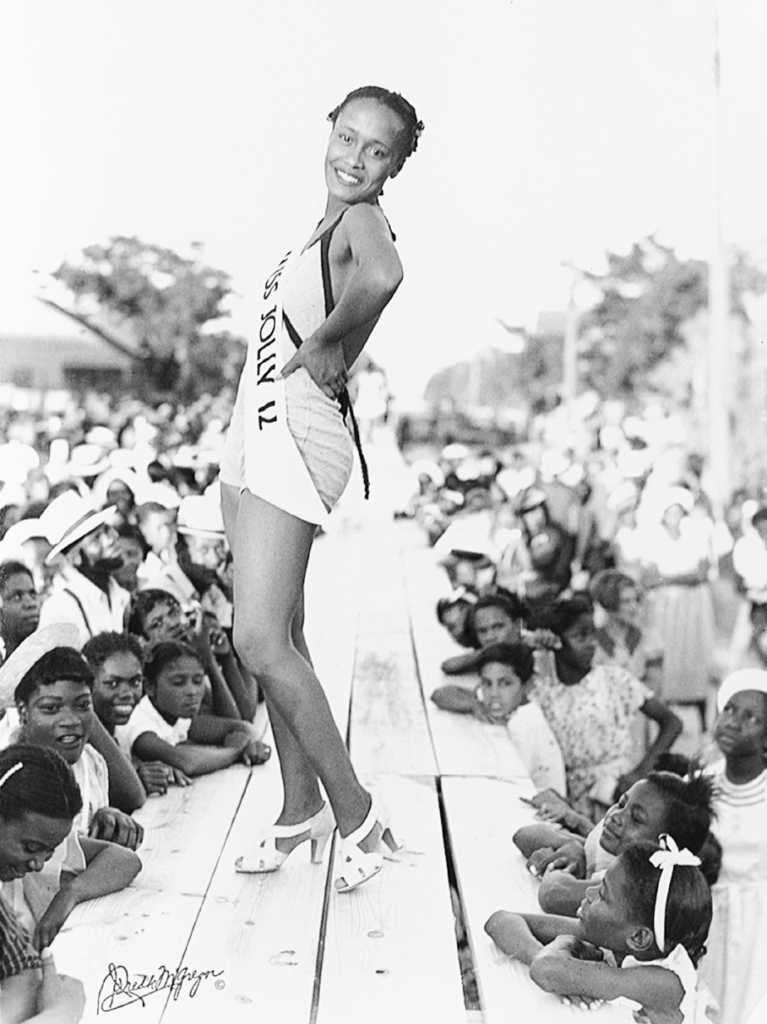

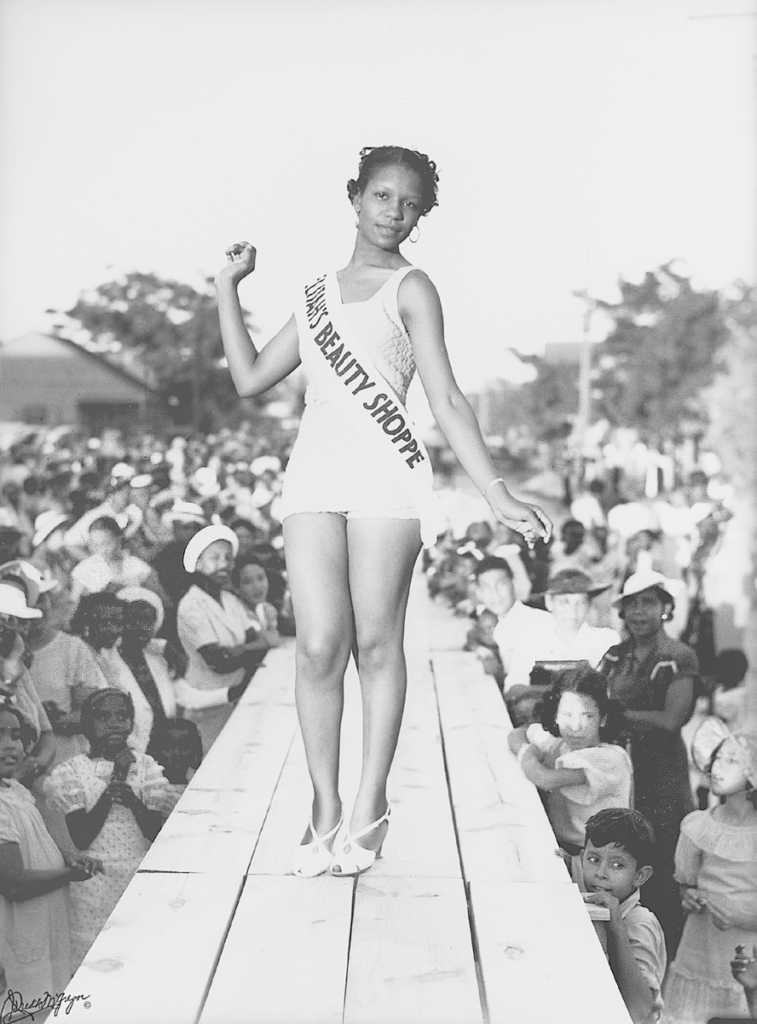

Riding a gaily decorated automobile down the streets of Northside is part of the fun of the 1937 Juneteenth celebration. (Courtesy of the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History, John Fred’k “Doc” McGregor Photographic Collection.)

Explore the History of Juneteenth and Emancipation

Rosewood is a historically African American neighborhood on the east side of Austin. It takes its name from Rosewood Avenue, which runs through the heart of the area. Rosewood was first settled by Europeans in the late 19th century, and beginning in the 1910s, the City of Austin adopted as official policy the goal of segregating African Americans in East Austin. Rosewood has been the official home of Austin’s Juneteenth, or Emancipation Day, celebration.

From slavery to freedom, to education, to achievement: these words reflect the goals of African Americans who first came as slaves with the Spanish to this part of the Texas coast. Freed by the Civil War on Juneteenth (June 19, 1865), blacks soon established an active and viable community, a significant part of which was defined by the black churches. Using photographs from individual collections African Americans in Corpus Christi reveals the history and people of Corpus Christi.

Through the voice of its people, this lively book relates the interesting and important role the Island City played during the war, including the story of the Union naval blockade, the dramatic Battle of Galveston, Unionists, dreadful epidemics of yellow fever, the surrender of Galveston as the last major port still in Confederate hands and the bondage and liberation of the island’s enslaved African Americans.

In the 19th century, Galveston shores were a gateway for immigrants to Texas and destinations beyond. Slaves, the forced immigrants, were brought to Galveston as property for sale. The largest slave trade operation in Galveston was implemented by Jean Laffite, a pirate. His slave trade business began around 1818. However, for the most part, slaves entering the port of Galveston were destined for other Texas cities and other states.