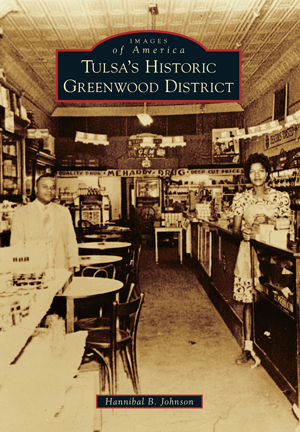

This article is an excerpt from Tulsa’s Greenwood Neighborhood by Hannibal B. Johnson

Tulsa, Oklahoma, “The Oil Capital of the World,” shone brightly at the dawn of the 20th century. Black gold oozed from Indian Territory soil, land once set aside for Native American resettlement. J. Paul Getty, Thomas Gilcrease, and Waite Phillips were among the men extracting fabulous fortunes from Oklahoma crude and living on Tulsa time.

As Tulsa’s wealth and stature grew, so, too, did its political, economic, and, in particular, race-based tensions. The formative years of this segregated city coincided with a period of marked violence against African Americans. In 1919 alone, more than two dozen race riots erupted in towns and cities throughout the country. That same year, vigilantes lynched at least 83 African Americans. The Greenwood District in Tulsa blossomed even amidst this “blacklash.” African Americans engaged one another in commerce, creating a nationally renowned hotbed of black business and entrepreneurial activity known as “Negro Wall Street.” Greenwood Avenue, just north of the Frisco Railroad tracks, became the hub of Tulsa’s original African American community. Eclectic and electric, this artery drew favorable comparisons to legendary thoroughfares such as Beale Street in Memphis and State Street in Chicago.

This parallel black city existed just beyond downtown, separated physically from white Tulsa by the Frisco tracks and psychologically by layers of social stratification. In it, African American businesspersons and professionals mingled with day laborers, musicians, and maids. African American educators molded young minds. African American clergy nurtured spirits and soothed souls. The success of the Greenwood District ran counter to the prevailing notion in that era of black inferiority. Fear and jealousy swelled over time. The economic prowess of Tulsa’s African American citizens, including home, business, and land ownership, caused increasing tension. Black World War I veterans, having tasted true freedom on foreign soil, came back to America with heightened expectations. Valor and sacrifice in battle had earned them the basic respect and human dignity so long denied at home—or so they thought. But America had not yet changed. Oklahoma had not changed. Tulsa had not changed.

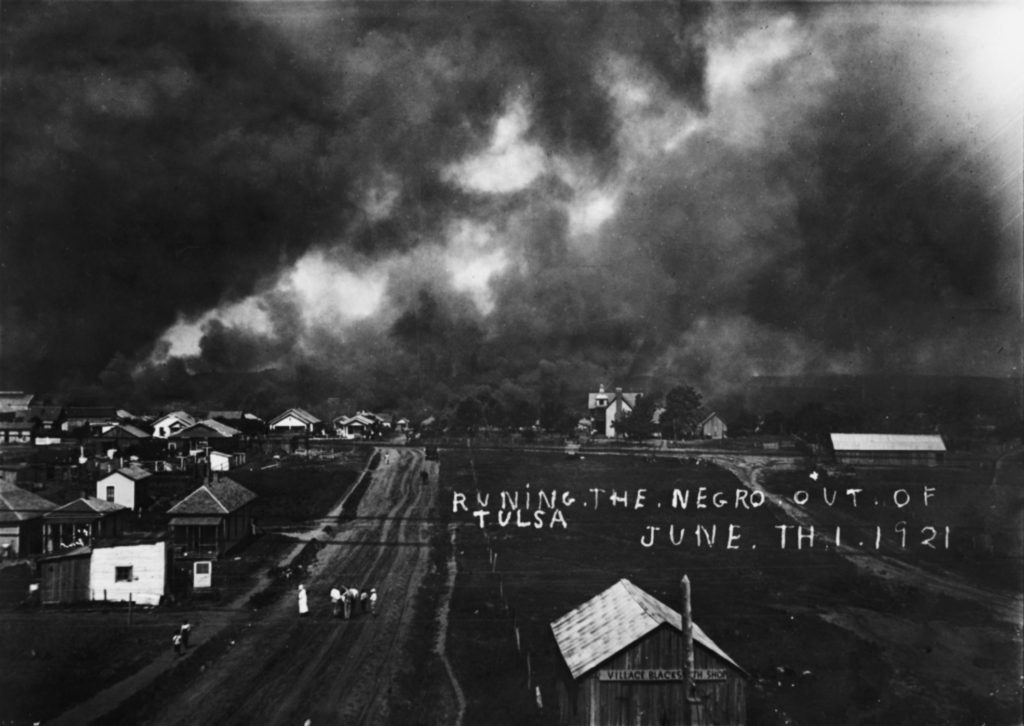

This photograph depicts the smoke-filled sky over the Greenwood District. The telling caption suggests a pogrom.

Courtesy of the Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

A seemingly random encounter between two teenagers lit the fuse that set the Greenwood District alight. The alleged assault on a 17-year-old white girl, Sarah Page, by a 19-year-old black boy, Dick Rowland, in the elevator of a downtown building triggered unprecedented civil unrest. Deep social fissures, however, lay at the roots of the riot, which included white angst over African American prosperity, land lust, and a racially hostile climate in general.

A local newspaper stoked the embers of Tulsa’s emerging firestorm. The Tulsa Tribune framed the elevator incident in black and white: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator.” Authorities arrested Rowland. A white mob vowed to lynch him. A small group of African American men marched to the courthouse to protect Rowland. Upon their arrival, law enforcement authorities implored them to retreat, assuring them of the teen’s safety. They left, but the lynch talk persisted. Jarred by these persistent threats and increasingly concerned for Rowland’s safety, more African American men assembled. Several dozen strong, these men, some bearing arms, trekked to the courthouse.

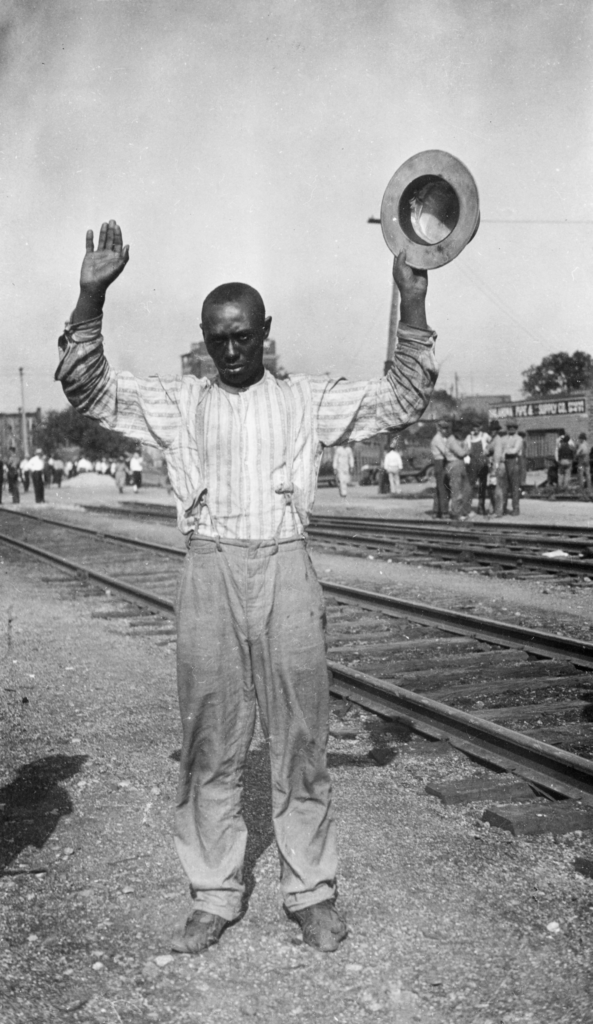

Thousands of black men were interned throughout the city as the riot wound down. As a condition of their release, they were given green cards—also known as American Red Cross Refugee Cards—to be signed by a white person willing to vouch for them.

Courtesy of Dana Birkes.

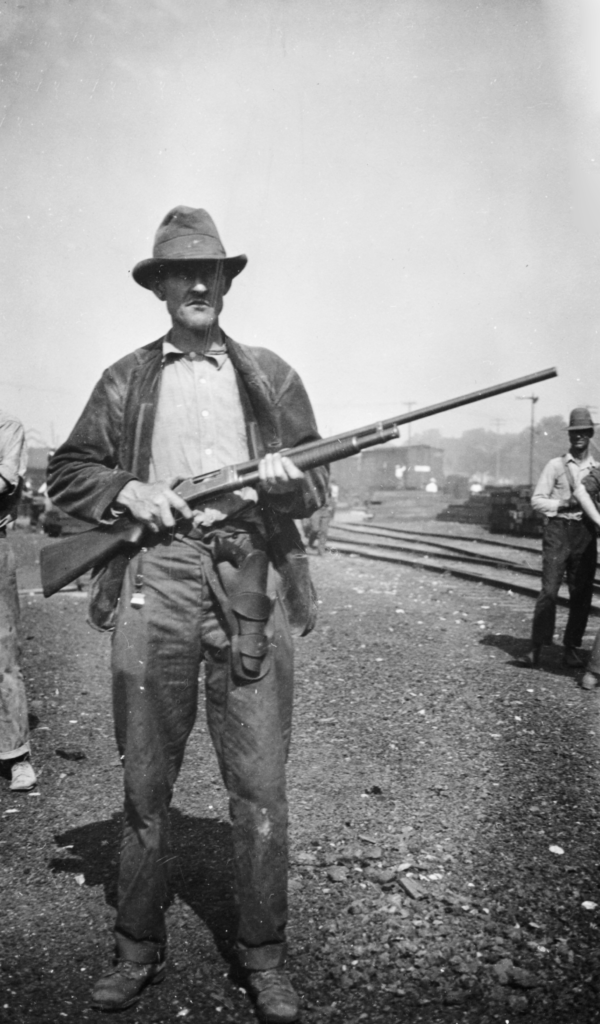

White men looted downtown pawnshops for guns and ammunition before invading the Greenwood District. Some shopkeepers complied with the looters’ demands; those who resisted had their inventories forcibly removed.

Courtesy of Dana Birkes.

There, they met and verbally engaged with the throngs of white men already massed. Two men struggled over a gun. The gun discharged. Chaos erupted. Soon, thousands of weapon-wielding white men invaded the Greenwood District, seizing upon the “Negro quarter” with seismic fury. Some law enforcement officers stood idly by while others placed themselves squarely along the racial fault lines, even deputizing the white hoodlums who would set ablaze the area derogated as “Little Africa.” As flames raged and smoke billowed, roving gangs prevented firefighters from taking action. In a 16-hour span, people, property, hopes, and dreams vanished.

The Greenwood District lay in utter ruin. The State of Oklahoma declared martial law in Tulsa. The Oklahoma National Guard eventually restored order. Authorities herded African American men into internment camps around the city, ostensibly for their own protection. Camp staff released detainees only upon presentation of green cards countersigned by white guarantors.

“I got caught right in the middle of that riot. Some white mobsters were holed up in the upper floor of the Ray Rhee Flour Mill on East Archer, and they were just gunning down black people, just picking them off like they were swatting flies.”

-Otis Grandville Clark, b. February 13, 1903, d. May 21, 2012

Image courtesy of the Tulsa World

Property damage ran into the millions. Casualties numbered in the hundreds. Some African Americans fled Tulsa, never to return. Local courts failed to convict even a single white person of a crime associated with the riot. Prosecutors charged dozens of African American men with inciting it.

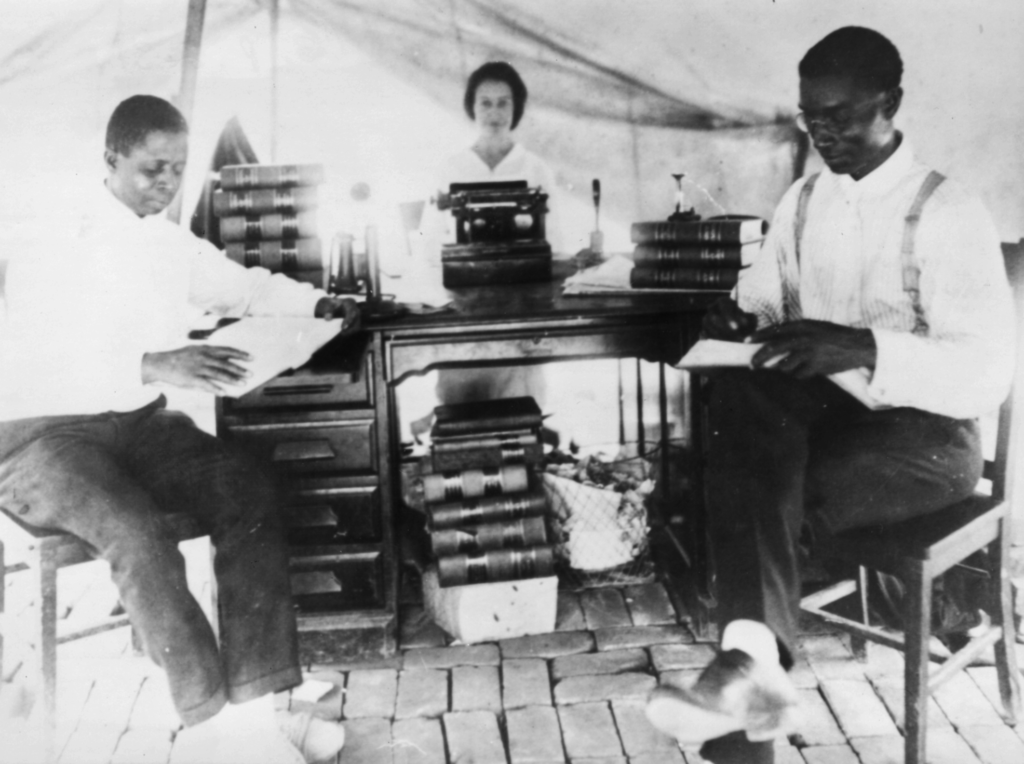

Even as the fires still smoldered, Greenwood District pioneers pledged to rebuild their community from the ashes. Official Tulsa leadership touted cooperation and collaboration, but hindered postriot reconstruction. The Tulsa City Commission blamed African American citizens for their own plight. City officials turned away outside donations earmarked for the rebuilding. Attorney Buck Colbert Franklin rebuffed Tulsa’s attempt to enact a more stringent fire code that would have made post-riot rebuilding cost-prohibitive for many.

Attorney Buck Colbert Franklin, right, works with colleagues in a makeshift law office to assist victims of the riot with legal claims. Franklin won a critical court decision that struck down a city ordinance that would have imposed strict rebuilding requirements in the wake of the riot. These new provisions would have made reconstruction cost-prohibitive for many African Americans. Franklin is the father of the late eminent historian, Dr. John Hope Franklin.

Image Courtesy of the Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

In the midst of the devastation, white allies surfaced. First Presbyterian Church and Holy Family Cathedral helped shelter and feed fleeing victims of the racial violence. The American Red Cross, heralded as “Angels of Mercy,” offered medical care, food, shelter, and clothing, and even established tent cities for the hordes left homeless by the riot.

African Americans shouldered their share of the load, too. Spears, Franklin & Chappelle litigated claims against the City of Tulsa and insurance companies and made urgent appeals to African Americans nationwide for assistance. Black builders secured lumber and supplies from surrounding states so reconstruction could commence. Entrepreneurs vowed to reestablish their businesses. Black churches rallied their parishioners. For Tulsa’s early African American denizens, the Greenwood District was much more than a business venue. It was home. Their determination and persistence ensured the survival of the community they knew and loved.

This c. 1923 group photograph was taken from the Frisco Railroad tracks at Boston Avenue in Tulsa’s Greenwood District. The dramatic and rapid post-riot rebuilding of the Greenwood District in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds speaks to the human spirit of Tulsa’s early African American pioneers.

Courtesy of the Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

Tulsa’s African American community proved remarkably resilient. In 1925, just four years removed from the riot, the community hosted the annual conference of the National Negro Business League.

By the early 1940s, scores of businesses once again called the Greenwood District home. Integration, urban renewal, a new business climate, and the aging of the early Greenwood District pioneers precipitated a pronounced economic decline beginning in the 1960s. The emergence of the Greenwood Cultural Center in 1983 signaled a new beginning.

The story of the Greenwood District speaks to the triumph of the human spirit. Now, a new chapter has begun. The Greenwood District, that black entrepreneurial center of old, has long since faded. In its stead is a new incarnation: an emerging arts, cultural, educational, and entertainment complex. This book explores, principally through pictures, the four central phases in the life of Tulsa’s historic Greenwood District: its roots, riot, regeneration, and renaissance.

ABOUT THE BOOK: In the early 1900s, an indomitable entrepreneurial spirit brought national renown to Tulsa’s historic African American community, the Greenwood District. This “Negro Wall Street” bustled with commercial activity. In 1921, jealously, land lust, and racism swelled in sectors of white Tulsa, and white rioters seized upon what some derogated as “Little Africa,” leaving death and destruction in their wake. In an astounding resurrection, the community rose from the ashes of what was dubbed the Tulsa Race Riot with renewed vitality and splendor, peaking in the 1940s. In the succeeding decades, changed social and economic conditions sparked a prodigious downward spiral. Today’s Greenwood District bears little resemblance to the black business mecca of yore. Instead, it has become part of something larger: an anchor to a rejuvenated arts, entertainment, educational, and cultural hub abutting downtown Tulsa.