How important is filming on location, rather than at the studio?

The answer lies in the opening scene of a 1960 Paramount film called The Rat Race. Tony Curtis has been playing his saxophone for tips on Midtown Manhattan’s kinetic Times Square. He gathers the coins from his open case on the sidewalk, packs up his horn, and walks around the corner—to Paramount’s “New York” street in Hollywood.

In an instant, the viewer’s suspension of disbelief disappears. You’re stuck on a lousy backlot you’ve seen a hundred times, and you don’t give a damn what happens to Tony Curtis anymore.

The problem is that Times Square is real, and Paramount’s street is phony. Times Square is a random collection of architectural quirks by different builders from different periods of time, haphazardly repaired, visibly cracked and worn down and given an accretion of grime; it’s a chaotic, noisy place where countless people have worked, dreamed, passed by and passed on. Paramount’s street, on the other hand, is a prop, a facade. Tiny details, especially the ones that register just below consciousness, matter when you’re trying to build a world.

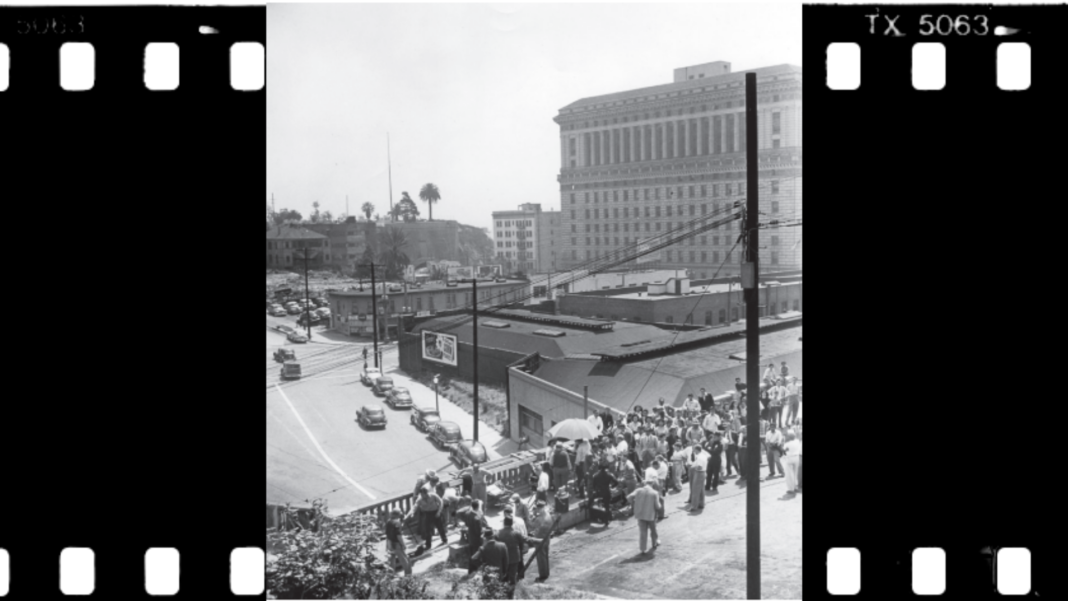

Filming in Bunker Hill

This is something all great directors grasp. When many postwar auteurs were looking to make their noir masterpieces, they found their perfect and authentic location in Bunker Hill, a neighborhood of fading Victorians, flophouses, tough bars, stairways and dark alleys in downtown Los Angeles.

A location like Bunker Hill provides its own inherent tension. Consider the Rat Race example. If they are filming in New York, the cast and crew must contend with changing light conditions, traffic, unreliable power sources and disruptive shop owners who feel they haven’t been properly compensated. It’s essential that everyone, especially the actors, get the scene right and move on, because another day of shooting on Times Square requires more city permits and another full day’s pay.

But back at Paramount, filming in “New York,” the cast and crew can spend as much time as they need to properly light the shots without worrying about the time of day. There’s no traffic, no curious pedestrians, no city noise, no permits and no excitement. If Tony Curtis keeps flubbing his lines, they can always come back tomorrow. The anxiety of getting it right the first or second time is gone. That’s why, when the two scenes—one on location, the other on the pristine and placid backlot—are juxtaposed on film, the difference between them is palpable. One has a lived-in feel, and the other is lifeless.

Los Angeles Times film critic Kevin Thomas noted just such a difference when he reviewed a 1966 Glenn Ford detective drama called The Money Trap, which interspersed scenes shot on both Bunker Hill and on MGM’s backlot. The film’s already “tenuous” credibility, Thomas wrote, “is completely undermined by the poor matching of actual Los Angeles locations with some of those old New York street scene sets with the familiar brownstone walkups. How can we accept Ford as a victim of environment—the poor boy who doesn’t quite make good—if we can’t believe in that environment itself ?”

Location vs. Studio

“The tremendous advantages of shooting on location, as opposed to studio, is you’re dealing with reality,” director Peter Bogdanovich says in his DVD commentary for the 1952 film Clash By Night, which was shot in Monterey, California. “It gives an authenticity and verisimilitude, immediately.” As a bonus, “The actors like it because they feel it’s real.” Bogdanovich recalls that Otto Preminger once told him that shooting on location forces a director to be more inventive “because you can’t move the walls.” In other words, unlike a studio designed for the sake of the camera, a real location restricts where that camera, along with the lights and the actors, can go. It challenges the director to try something new.

Veteran cinematographer James Wong Howe agreed. “Artistically, I would always rather be on real sets, on location, in the natural setting versus sets built in a studio,” he told film critic Alain Silver in 1970. “It’s rather ridiculous when you have light from a single source, whether it’s the sun or a solitary candle, and the set is lit so that objects cast three or four shadows. A real house has a ceiling and four walls, and one has to change the way of lighting. In a studio, without a ceiling, it’s easier and faster for a cameraman to light. But to me these are false lights.”

If “authenticity and verisimilitude” seem irrelevant within a theatrical medium, consider that general film audiences are much more literal in their tastes than live theater audiences. They wouldn’t tolerate a movie version of Waiting for Godot with just a cardboard tree on an otherwise empty stage. (In fact, they probably wouldn’t tolerate sitting through Waiting for Godot.) They need the illusion of quotidian reality, especially on the big screen, where actors must overcome the unnaturalness of being oversized creatures formed out of light and shadow.

Consider also that letting in the flow of reality can offset or soften the improbability of oddball characters, farfetched plots and the artificial mood lighting so important to many films. The Christian Science Monitor’s Edwin F. Melvin, reviewing the 1951 film noir Cry Danger, observed that its circuitous story “may not be quite so believable as the realistic photography in some of the less pretentious sections of Los Angeles.”

The January 14, 1951 edition of the Hollywood Reporter praised the film’s director for choosing “to shoot all exterior footage against backgrounds of downtown Los Angeles [and] creating an air of authenticity difficult to capture on celluloid.”

In early 1953, the Los Angeles Times’s Philip K. Scheuer wrote: “Where [The Turning Point] gains the most conviction is from its on-the-spot locations.” The location Scheuer was talking about, of course, was Los Angeles’ Bunker Hill.

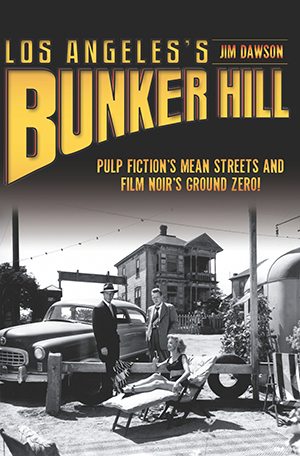

Los Angeles’s Bunker Hill: Pulp Fiction’s Mean Streets and Film Noir’s Ground Zero!

By Jim Dawson

When postwar movie directors went looking for a gritty location to shoot their psychological crime thrillers, they found Bunker Hill, a neighborhood of fading Victorians, flophouses, tough bars, stairways and dark alleys in downtown Los Angeles. Novelist Raymond Chandler had already been there exploring the real-life “mean streets” that his hardboiled detective, Philip Marlowe, prowled in the writer’s exacting prose. But the biggest crime was going on behind the scenes, run by the city’s power elite. And Hollywood just happened to capture it on film. Using nearly eighty photos, writer Jim Dawson enlarges the record of L.A. history with this grassroots investigation of a vanished place.