A year ago, when the world was first wrestling with the coronavirus, one of the early vectors was cruise ships. But if you think that’s the first time a terrible disease overwhelmed a ship, you don’t know the story of the cholera outbreak on the James Monroe.

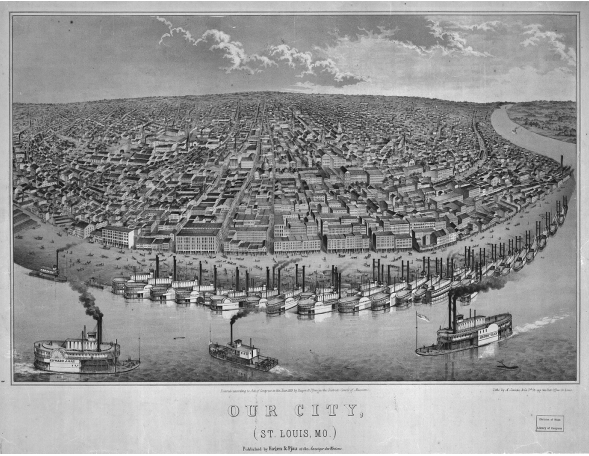

In 1849, this steamship departed from St. Louis, with many of its passengers heading toward California and its booming gold rush. Their trip was interrupted when cholera broke out on board. It was a shocking event, and yet in 2021, it is also a familiar one. The best way to experience the cholera outbreak is to read this letter written by a female survivor. She addressed “To the Editors of the North American and U.S. Gazette.”

Here is the James Monroe‘s story in her own words:

“Permit a woman who has been rescued from the very jaws of death by a people whom she never saw, and scarce ever heard of before the [10th] of last month, the use of one of your columns for a single morning to express her gratitude, and to render honor to whom honor is due, as it is the only return she will ever be able to make for so much kindness, except to remember them in her prayers to the Almighty Ruler of the Heavens and the Earth.

I ask this favor not because I have any right to demand it, but because the paper is an old acquaintance, my father having been a reader of it for a long series of years, whilst it was under the editorial supervision of Mr. Chandler. I was a passenger on the steamer Monroe, bound from St. Louis to St. Joseph on the Missouri river, and on the morning of the [10th] of May, arrived at this port, the capital of the State.

“At the time of our arrival the dead, the dying and the sick were strewn everywhere about the ill-fated boat, and to get away from such a terrible pest house was the desire of every one. Before the boat touched the wharf the passengers were informed that it was impossible to continue the voyage on account of the cholera on board, and accordingly nearly two hundred of us, all carrying the seeds of the terrible pestilence in our systems, inundated this beautiful picturesque village. Not one human being in the town, so far as I know, had ever heard of one of us before, but to the honor of these people be it said that we were neither friendless or homeless.

Immediately upon touching, our Captain deserted the boat, leaving the dead body of one of his own servants on board, shut himself up in a hotel, and forbid any access to him on any account. That night he left for St. Louis, and immediately after his arrival there, died of the epidemic. Oh! The sudden and terrible judgement [sic]. The clerk and owner of the Monroe ran away also, and through the columns of the Reveille, at St. Louis, calumniated most grossly a people whose kindness, sacrifices and philanthropy he was altogether unable to appreciate. Being thus thrown ashore, our voyage broken up, and deserted by the officers of the boat, we were thrown, with the terrible pestilence among us, upon the charity of this village of about twelve hundred souls.

As might have been expected,—especially as the visitation of the cholera had been anticipated, and in such anticipation the village had been thoroughly cleansed, and was then perfectly healthy,—a great terror seized the people; but at the very threshold, in addition to the prompt energy of the physicians, appeared a guardian spirit—the Hon. James W. Morrow—whose self possession, cool courage, and indomitable energy, rallied around him a body of young men, without whose aid the sufferings of the sick and the dying must have forever remained untold. At his suggestion, the well were separated from the sick; the Episcopal and Presbyterian churches, and the White House and unoccupied hotel, were turned into hospitals, and the well furnished with all the vacant houses in the town.

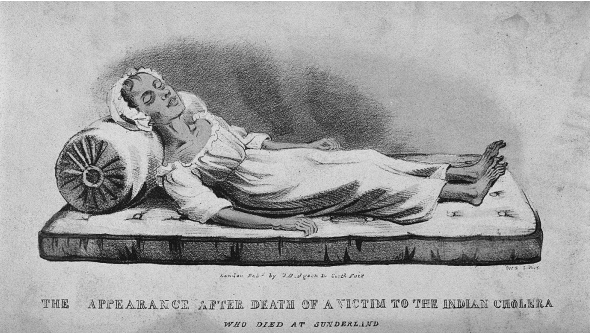

And now the work of death commenced in right good earnest. In less than a week more than sixty of the Monroe’s crew and passengers were in their graves, and at the end of about that time the dread scourge commenced its ravages amongst the citizens, and up to this date about twenty-five have died.

In less than three days I saw father, mother, brother and sister, fall before the dread destroyer, and in the night of the fourth day my own summons came. I thought I had prepared to answer it, for I was without hope in this world, but Providence has ordered it otherwise, and I now live to tell the tale. To Dr. Wm. A. Davison, Judge Morrow, Capt. Parsons and Mr. Albert Baber I owe my life.

Never, never, shall I forget the horrors of the first night of my attack. It was dark and tempestuous, and I had just seen for the last time the purple corpses of my parents, brother and sister, but true to their great mission, the gentlemen I have named provided me with a female nurse, and some of them, I do not know who, watched in the adjoining room until the morning. Never shall I forget the remark of Judge Morrow immediately after I had passed, (although I did not then know it) the crisis of my disease. Coming in, he put his hand upon my forehead, felt my pulse and feet, and turning around spoke to Capt. Parsons, saying, “thank God, Parsons, she is saved.” A re-action was taking place, and the next time I saw Dr. Davison, the kind, good man, he said to me; “you are out of danger if you are prudent.” The frequent recurrence of Judge Morrow’s name in this incoherent sketch is excusable upon two grounds—he is not unknown to fame in the West as a jurist, and as a writer of politics and pungent humor; but the tribute is due to him as a philanthropist. The dangers to which he has exposed himself to render assistance to entire strangers, his activity and effective energy in a most appalling and trying crisis, his disinterested sacrifices, and his affectionate offices to the dead, make it his due. He seemed to be possessed of the power of ubiquity—being everywhere at the same time—when he was away, everything seemed to be out of joint—the sick called for him and invoked his assistance—even his tread upon the stair was the words of hope to me. It was really affecting to see the rescued gather around him as he passed along the streets, and one morning when it was rumored that he had been assailed during the night by the fell destroyer, a thrill of horror ran through the whole town, and many of the city fathers flew to his residence to ascertain the truth. They returned almost shouting that it was nothing but a bilious attack brought on by exposure and fatigue.

I do not feel justified in closing this long—quite too long—epistle, without rendering in the name of the dead and living, to the people of Jefferson City, the Capital of the state of Missouri, my sincerest thanks—and most especially to Drs. Davison, Winston, Edwards, Dorris, Matthews and Krauser, to the Babers, Millers, Kerr, Hartt, Murray, Deitz, McKenzie, Cloney, Shubert, Green, the Parsons and Lusks, the Misses Lusk, and Mrs. Linn and her son, young Dr. Linn, and Dr. Wells, and others whose names I cannot now call to my memory. May the Providence of God protect this town always.”

In 1849, a steamship named after President James Monroe headed from St. Louis to Council Bluffs, Iowa. The passengers were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from Philadelphia. At St. Louis, they were joined with a group of California gold diggers from Jeffersonville, Indiana. But their trip was interrupted when cholera broke out on board. Local fourteen-year-old James McHenry discovered the steamship after it landed at Jefferson City and observed the dead and dying victims along the riverbank. Author Gary Elliott details the history of the cholera outbreak in the city and its far-reaching effects.