Houston, Texas, that sprawling, noisy, ambitious city on the Gulf Coast has had some epic rallies since its founding in 1836. But as big as Houston is, it’s not surprising that the community hasn’t settled on a single public space for protests, parties, vigils, and celebrations. Over the decades, Bayou City has built up its central business district, only to watch as sprawl sent tens of thousands to the suburbs, then refocused on its core with revitalized public spaces and economic incentives to encourage Houstonians to live, work, and play Downtown.

The Rice Hotel

Few would argue that the Rice Hotel is one of Houston’s signature landmarks. Built on the site of the former capital of the Republic of Texas, the 17-story brick hotel with wraparound balcony has hosted presidents and astronauts, debutantes, and wildcatters. For the first half of the twentieth century, it was the place where Houstonians gathered.

In 1918, a crowd of nearly fifteen thousand assembled Downtown in front of the Rice Hotel to honor the service of the Allied forces following the end of World War I. The so-called World War I Victory Sing came weeks after well-wishers heard the news of an armistice in Europe and jammed the streets Downtown.

Hometown hero Howard Hughes, already famous for his father’s oilfield equipment empire and his time as a Hollywood producer set his sights on aviation. In 1938, Hughes set a record for flying around the world in three days, nineteen hours and seventeen minutes. Returning to Houston, Hughes received a hero’s welcome. The aviator was greeted to a Downtown parade and banquet at the Rice Hotel.

On May 30, 1942, one thousand local men, also known as the Houston Volunteers, were inducted into the United States Navy following the loss of the USS Houston in the Battle of Sunda Strait earlier that year. Thousands witnessed the Downtown rally and parade that included several hundred navy officers and four bands, while Rear Admiral William Glassford swore in the volunteers and spoke about Houston’s final battle. The mayor read a message from President Franklin Roosevelt, who had had four presidential cruises on the USS Houston.

City Hall

In 1939, Houston’s new City Hall opened. The limestone-clad Art Deco structure replaced the Market Square City Hall, where, from 1841 to 1939, four different wood-frame buildings were located. The new City Hall featured a reflecting pool and public park in front that eventually became a site for Houstonians to gather in times of celebration and in times of protest. In recent years, the City has recognized the power of this place and allowed for more events there. Today, City Hall is occasionally lit with thematic colored lights honoring causes, holidays, or even world championships.

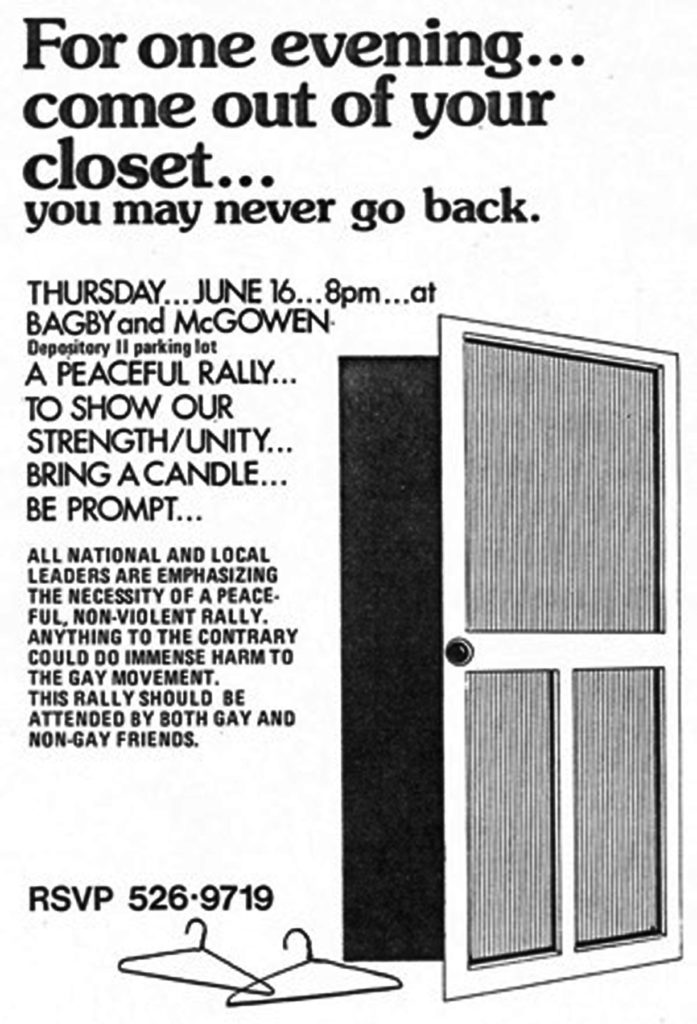

In the summer of 1977, gay rights opponent Anita Bryant was invited to perform at the Texas State Bar Association’s annual convention. When Houston’s gay community heard the nation’s leading anti-gay voice would be speaking in Houston, the once-fractured group mobilized into a united front. Nearly three thousand gay, lesbian and straight Houstonians gathered at a Midtown bar and marched peacefully Downtown, past the site of the convention, to a rally at the Houston Public Library, across the street from City Hall, where the crowd grew to over eight thousand.

In 1979, Houston’s first official gay pride parade rolled down Lower Westheimer with banners declaring “United We Stand.” In subsequent years, the pride parade would grow to include floats and marching bands, reschedule to nighttime and become the signature Montrose party. By 2015, the parade would outgrow Montrose’s narrow streets, moving Downtown.

The Houston Astros were celebrated in a Downtown victory parade and rally at City Hall in 2017. Hours before the parade, Downtown parking garages were overflowing with eager fans. Starting before noon, a seemingly endless wave of Houstonians in Astros orange filled Downtown streets. Players, coaches, and everyone in the Astros family rode on firetrucks, greeted by an estimated 750,000 jubilant fans, some who had waited fifty-six years to see Houston win it all. The parade ended on the steps of City Hall, where the team was greeted by local and state elected officials, eager to be photographed with the Houston heroes. Well into the weekend, high-rises kept their celebratory messages spelled out in lit windows, and City Hall remained illuminated in Astros orange for days.

Today, the park in front on City Hall is just as likely to have a farmers’ market pop-up or fenced-off Art Car Ball as it is to host a 22,000 Women’s March or a 60,000 person Black Lives Matter protest from Discovery Green, on the opposite side of Downtown, to the steps of Houston’s city government.

READ MORE: Civil Rights & Social Justice History