Adapted by Christen Thompson, Editorial Director and Charleston Resident.

In the days following the June 2015 shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church by white supremacist Dylann Roof, the nation waited to see what Charleston would do. Just two months earlier, a black man named Walter Scott was shot while running away from a police officer during a traffic stop in North Charleston. Both tragic events followed on the heels of unrest in reaction to the police related and caused deaths of black men in cities across the country–in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray in April; in Ferguson and St. Louis after the death of Michael Brown in August of 2014; in Texas after the death of Eric Garner in New York in July of 2014.

Perhaps as a result of the pleas of the family members of those killed in the church, known as the Emanuel Nine, Charleston did not riot, but mourned in peace. The city’s placid, unified response earned praise from politicians and activists across the country. A common refrain among locals was “We’re different. Charleston is different. We don’t have the same racist problems as other cities.” For a city that grew to international prominence because of its role as the nation’s capital of the slave trade, a city that, as noted in a 2011 Post and Courier article, was “built on slave labor and, for nearly 200 years, thrived under a slave economy,” these feelings seemed at odds with reality.

As College of Charleston professor and Avery Center Researcher Edmund Drago explained in the introduction of Charleston’s Avery Center, some Charlestonians “are loath to admit that a slave market ever existed in the city, but even the progeny of the slave-holders concede the impact of slavery on the culture of the Low Country.”

And so it would appear that the idea that Charleston is exempt from the repercussions of slavery is very much contradictory to the truth. In fact, Charleston is the kind of place where prejudice and systemic racism were actively perpetuated by people in power. Its history is filled with examples of leaders flagrantly ignoring civil rights laws and dismissing calls for reform. And we don’t have to look back that far to see that this is true, and how much of our present is viewable in our past.

The following stories are excerpted and adapted from Charleston’s Avery Center: From Education and Civil Rights to Preserving the African American Experience by Edmund L. Drago, Revised and Edited by W. Marvin Dulaney.

The Charleston Movement

The civil rights movement in the Holy City

Perhaps even more than the Civil War, the civil rights movement united white South Carolinians against what they considered another Yankee invasion. Low Country politicians vied with one another in denouncing integration. The First Congressional District congressman L. Mendel Rivers described the civil rights movement as “an unholy alliance to destroy the white civilization—and the orderly way of life as it is known in the South.” Before 1956 Ernest F. Hollings was firmly in the segregationist camp. The local newspaper, particularly Thomas R. Waring, was extremely supportive of the segregationist-oriented White Citizens’ Councils.

Ironically, Mendel Rivers’s successful efforts to expand the federal military presence in the Low Country fostered a modernization which opened the door to federal desegregation. In 1953, after prodding from the Eisenhower administration, the navy acted to end segregation at the country’s southern bases. The Charleston Naval Shipyard desegregated its cafeteria, while an alarmed local newspaper correctly predicted: “Navy To ‘De-segregate’ Toilets Next.” Despite white Charlestonians’ view of the movement as a Yankee-imposed Second Reconstruction, much of it was homegrown.

I. Sit-Ins & Merchant Strike

1960

The Charleston sit-ins of April 1960 were part of a popular national grassroots movement begun at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1959. Burke High School students conducted the local effort. According to James G. Blake, president of the school’s Junior NAACP the inspiration for the sit-ins arose from the classes of the two Burke teachers. Specifically, the plan entailed targeting lunch counters at several variety stores, including F.W. Woolworth, W.T. Grant, and S.H. Kress. In early April 1960 twenty-four students were arrested and detained until the NAACP put up bail.

City authorities managed to contain the demonstrations by not overreacting, but the issue remained potentially explosive. On April 8, 1962, the Charleston NAACP held a mass meeting at St. Matthew Baptist Church, in which the state conference president, J. Arthur Brown, and those assembled publicly delineated their grievances against the King Street merchants:

- They employed no black sales personnel, “although 50 to 85% of the King street trade is derived from Negroes.”

- Many refused to accord blacks courtesy titles or allow them to use their lunch counters.

- They also discriminated against them in “rest-room, drinking fountain and other convenience facilities.”

The group launched a protest picketing and “selective buying” campaign. Within a year the Charleston movement was born, “backed by the NAACP—national organization, state conference and Charleston and North Charleston branches, including youth councils of each branch.”

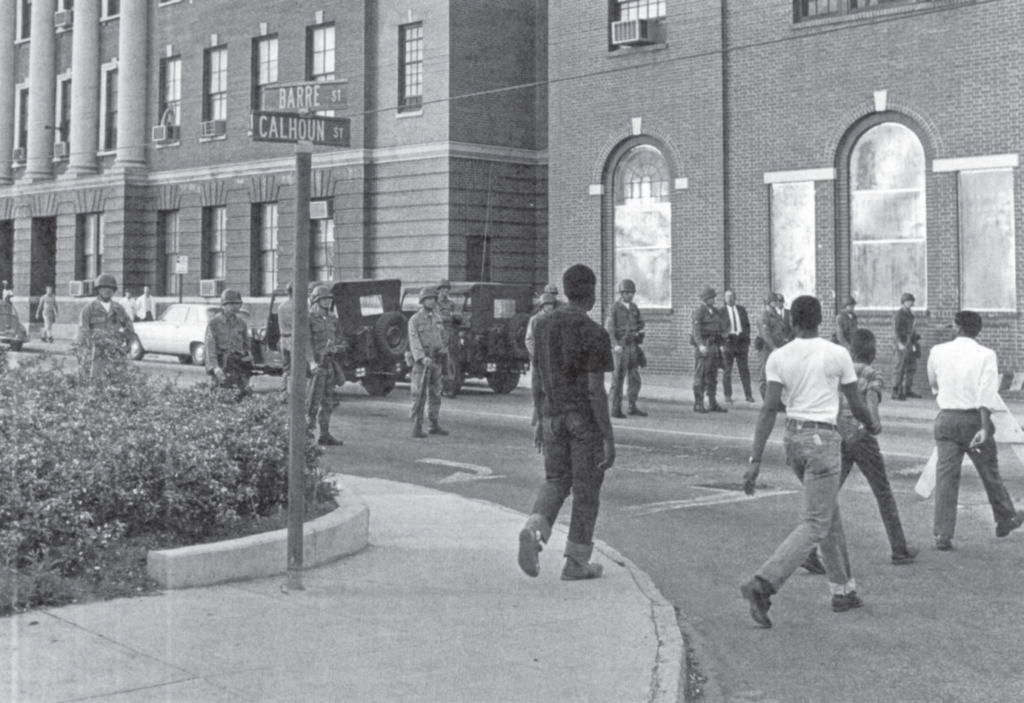

The campaign was kicked off at a “mass meeting June 7, 1963 at Calvary Baptist Church where James G. Blake…sounded ‘The Battle Cry of Freedom.” Composed of volunteers pledged to nonviolence, the Charleston movement held “nightly meetings, rotating at different churches.” Demonstrators picketed “outstanding stores in King Street for better job opportunities and desegregation of store facilities, waiting rooms, lounges.” On June 9, 1963, the demonstrations began with a prayer march. Motels, theaters, and restaurants were the first targets. Within two weeks more than two hundred persons were arrested.

Related: “Celebrating the History of the Greensboro Sit-ins through Pictures”

Students, led by James G. Blake, formed the core of the demonstrators. A graduate of Burke High School, Blake was a veteran of the movement. He attended Highlander, together with Septima Clark and Bernice Robinson. In 1960 Blake led the Charleston sit-in efforts and was a member of Burke’s Junior NAACP. He left Charleston to attend Morehouse College in Atlanta. In 1963 he returned to the city as a youth member of the NAACP’s national board of directors.

On June 19, 1963, Blake made public the demands of the Charleston movement:

- Appointment of a biracial committee to study the problems of segregation and discrimination;

- Desegregation of all restaurants, theaters, swimming pools, and playgrounds;

- Upgrading in the rank of Negro policemen;

- Equalization of job opportunities for blacks;

- Elimination of segregationist practices at the state-supported Medical College of South Carolina.

Other demands later included the appointment of blacks to a housing committee to help families displaced by the proposed cross-town expressway, inclusion of blacks in white-collar jobs filled by the city, and withdrawal of all charges against those who took part in the demonstrations.

RELATED: “Surviving Parchman Farm: The Ordeal of 1965” via Crime Capsule

By the first week of July it was clear to the white establishment that the Charleston movement was broadly based. Moreover, the movement received a boost when the NAACP executive secretary, Roy Wilkins, visited the city and addressed a meeting at Emanuel AME Church. Facing a black community and economic pressure on downtown merchants, Charleston’s city council obtained a temporary injunction against further demonstrations. The mayor J. Palmer Gaillard Jr. also agreed to meet with black leaders to “discuss the present problems.” After talking with the mayor in closed session, four black leaders, J. Arthur Brown, B.J. Glover, B.J. Cooper and Herbert U. Fielding, announced little progress.

On July 16 when the decision was to be made on the continuance of the injunction, five hundred demonstrators gathered at the office of the Charleston News and Courier to protest its editorial policies.

Exactly what happened is not clear. Authorities proclaimed it a “near riot,” although those involved were not so sure. Mass arrests followed.

The incident at the News and Courier stunned a city that prided itself on its lack of racial confrontations. After the seventh week of demonstrations the mayor and city merchants were ready to come to some sort of accommodation. By mid-August the merchants nearly all had fallen into line. The head of a local chapter of the National Association for the Preservation of White People complained bitterly that the businessmen had “capitulated” to the demands.

Gaillard told the press he would “rebuff ” the movement’s ultimatum, but he consented to the core of their demands, save for the desegregation of city playgrounds and swimming pools. Gaillard also accepted a fourteen-member voluntary “bi-racial community relations committee.”

By Christmas 1963 desegregation had made some inroads into Charleston. In 1960 after the sit-ins the downtown Charleston library had quietly desegregated its facilities. The downtown bus station eliminated separate facilities. Some of the hotels and lunch counters were also desegregated. Likewise, desegregation of the city’s schools, public and parochial, began in the fall of 1963. Finally, there was some evidence that the “employment of Negroes in downtown retail stores…has been steadily increased.”

II. Mary Moultrie and the Medical College Hospital Strikes

1969

If the civil rights movement in the Low Country can be viewed as a progressive uniting of all segments of the black community, then the Charleston hospital strike of 1969 was the final stage in which the movement addressed the concerns of the most poorly paid and discriminated-against sector in the black community, the working women, especially those who were heads of households.

Led by Mary Moultrie, these black hospital workers managed to mobilize the various Low Country civil rights organizations as well as the national labor movement behind their 113-day strike. Their success, in part, was based on the entire evolution of the civil rights movement in the Low Country, which Averyites did much to shape.

One of the major unresolved demands of the 1963 demonstrations was the issue of discrimination at the city’s Medical College (now University). In February 1965 the NAACP organized a protest march in part to “initiate action…to bring an end to segregated practices at the Medical College.” Probably because of such publicity, the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) named a four-person committee “to inspect the S.C. Medical College Hospital for compliance with the [Civil Rights] act.”

Such efforts, however, did little to help the largely black and mostly female paraprofessional corps at the Medical College Hospital and the Charleston County Hospital. Poorly paid ($1.30 per hour) and discriminated against, these nonprofessionals (licensed practical nurses, nursing assistants, dietary staff, orderlies, and janitors) were sometimes given professional duties.

Their jobs included training young white professionals, who were usually paid more but were not always as proficient as the blacks who trained them.

In February 1968 five black nonprofessionals about to go on duty asked the white nurse for the patients’ charts. She refused. The five blacks walked off the job and were fired. The incident was no surprise to Mary Moultrie. The daughter of a Charleston Navy Yard worker, she had gone to New York City, where she was hired as a licensed practical nurse. When she returned to Charleston in 1966, the Medical College slotted her as a nurse’s aide. But Moultrie was no novice to organization.

Not only was she knowledgeable about unions, she had once worked with Guy Carawan and Esau Jenkins on community projects. With the help of activist William Saunders, Moultrie met with Reginald Barrett and Isaiah Bennett, the business director of the local tobacco workers union state director of the National Hospital Workers. The women were eventually reinstated but recognized that some organizing was necessary for them to keep their jobs. The meeting with Barrett made it clear that the problems they faced were common throughout the Medical College.

With Bennett’s blessing, ten workers gathered “for weekly meetings at the ramshackle tobacco union hall.” The group eventually organized 550 of the 600 nonprofessional workers at the Medical College Hospital and at the Charleston County Hospital. It was logical that the group should meet there because in 1945 the tobacco union had gone out on strike to raise wages from eight to thirty cents an hour. One of the veterans of the strike, Lillie Doster, provided Mary Moultrie with timely advice.

Determined to “resist this union in its attempts to get in here with every legal means at our disposal,” William McCord, president of the Medical College, refused Mary Moultrie’s written request for a meeting and one from John Cummings, president of Local 15A.. Moultrie’s request coincided with big labor’s nationwide effort to organize hospital workers. Their affiliation with New York Union 1199 gave the new Charleston Union 1199B access to national labor support. Labor’s friends in Congress would pressure the Nixon administration to settle the strike amicably.

As pressure mounted the president, William McCord agreed to meet with Moultrie and a delegation of workers, but a March 18 meeting broke down when McCord named eight hand-picked employees as part of the workers’ delegation.

The next day Moultrie and eleven other activists were fired, beginning the 113-day Charleston hospital strike.

Moultrie and 1199B profited mightily from labor support, but they were able to mount such a successful challenge only because of the foundation laid by the civil rights movement. In a sense, the Charleston movement was a kind of rehearsal for those demonstrations mounted during 1969. The churches, the youth, and the NAACP again rallied to the cause.

RELATED: “The True History Behind The San Marcos 10”

No Averyites were involved directly in the walkout. They were of an older generation than Mary Moultrie’s. Few belonged to the working poor, but the rank discrimination against blacks prevalent at the Medical College made them receptive to the cause. Perry Metz, for example, had been “persistently insulted” during priestly visits to the hospital. His fellow minister, Henry L. Grant, head of the city’s St. John’s Episcopal Mission, remembered a white nurse’s yelling, “Boy, you can’t go down that hall” as he attempted to administer the Sacraments to the sick. When the strike began, Grant was a leader, and Metz’s Zion Olivet United Presbyterian Church became a place “where the workers often met for rallies.” 43 Other Averyites provided less direct but valuable support.

In June the committee appointed by HEW, citing thirty-seven civil rights violations, requested that the Medical College submit an affirmative action plan or risk losing federal funds.This action negated McCord’s assertions that the strike did not involve civil rights. It also caused the establishment, at least temporarily, to take a more moderate stance. The governor, Robert E. McNair, indicated his willingness to comply with federal guidelines, and McCord seemed on the verge of rehiring those fired as well as those striking. Only the intervention of L. Mendel Rivers and J. Strom Thurmond forced HEW to back down, aborting what might have been the beginning of a move toward real negotiations.

“Union Power, Soul Power.”

The strike was settled successfully because of a combination of “Union Power, Soul Power.” Specifically this involved uniting labor and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). According to Mary Moultrie, Septima Clark was instrumental in unifying the two groups behind the strike. In bringing such prominent national civil rights leaders as Coretta King and Ralph Abernathy to Charleston, SCLC bolstered community support for the mass marches, the demonstrations and the boycott of the city’s public schools and the downtown merchants.

The arrests of Abernathy galvanized the community and helped bring the issue to a head. As the strike became increasingly costly to Charleston, Gaillard named a Citizens’ Committee to seek ways of ending the dispute. The presence of Esau Jenkins on the committee suggested that the mayor was serious in his efforts. However, Gaillard found his hands tied. McNair declared that the state could not bargain with any union. Some people advocated closing the Medical College permanently. The strike ended because the Nixon White House wanted the strike settled; it feared growing national racial confrontations.

A prominent Charleston banker, Hugh C. Lane, conceded privately that conditions for blacks at the Medical College were scandalous. Rather than alleviating the problems, McCord’s administration compounded them by its inept handling of the strike. By threatening to cut off funds, the government hoped to persuade the state’s white establishment to come to terms. Moreover, there was some indication that some of the local strike leaders, unhappy with the actions of their outside allies, were willing to negotiate. McNair persuaded Saunders and Grant to mediate the negotiations. Saunders helped the two sides hammer out an agreement, which called for:

- The rehiring of all workers on the payroll as of March 15.

- The creation of a six-step employee grievance plan.

- The promise of $1.60 per hour minimum wage.

On June 27 the strike ended at the Medical College. By July 19 a settlement was also reached with the union at the Charleston County Hospital.

The hospital strike produced few lasting benefits for the workers directly involved. They had settled for a memorandum of agreement rather than a written contract. The grievance procedure failed because the hospital handpicked the board administering it, and the hospital reneged on a promise to allow workers to pay their union dues via a check-off system at the credit union.

After several years of harassment Moultrie left the hospital and Union 1199B ceased to exist. Despite its failure, the hospital strike was part of a long-term civil rights movement that registered considerable collective impact on the Low Country. That effort had united a Low Country black population historically splintered by color, class and geography.

Moreover, in mounting such an impressive effort in the 1960s with virtually no local white support, it did much to lift the self-esteem of Low Country blacks. It shattered white Charleston’s self-serving image of itself, or what Mary Moultrie termed the “‘We have always been good to our Negroes’ smugness.” For years blacks had been tolerated, Moultrie noted, “often…with fondness only because…someone had to iron Missy’s dresses and stroll quaintly through the white neighborhoods selling raw shrimp.”