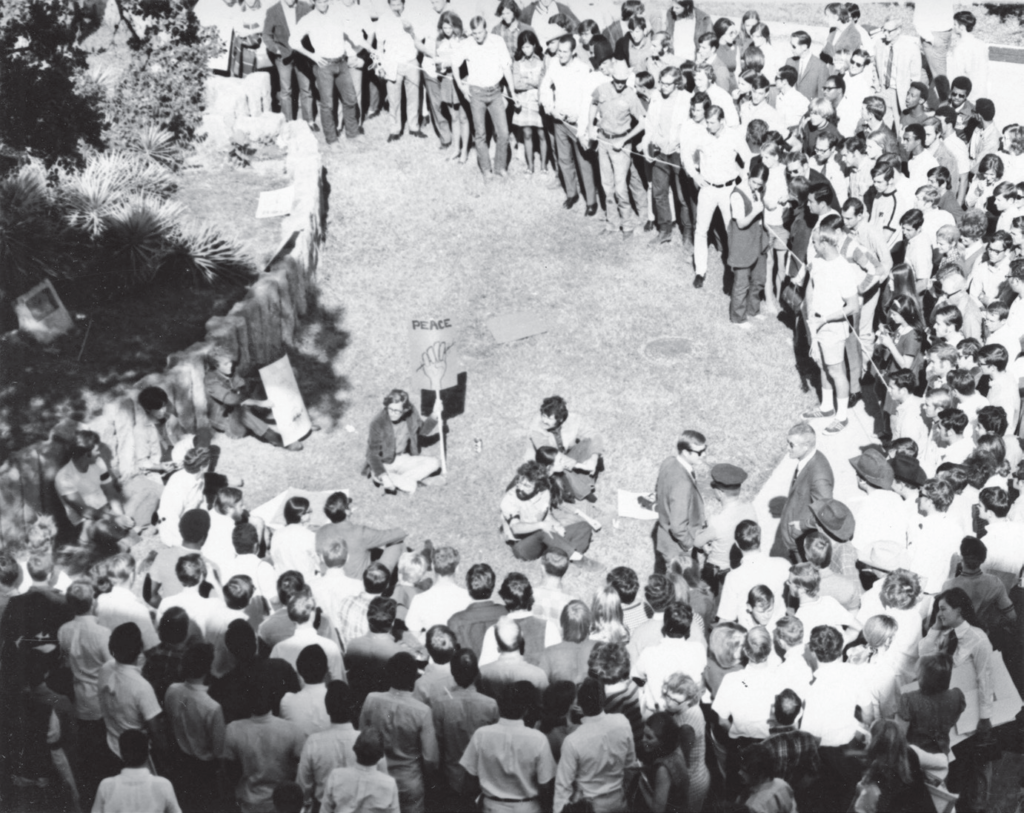

The politically and socially turbulent 1960s changed the United States forever. Groups of mostly young Americans sought to overturn the status quo for African Americans and to end the contentious Vietnam War. National groups brought their message to all corners of the nation, finding energetic followers on college campuses. One such group, the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (New MOBE), arrived at Texas State University in 1969. Suddenly, the conservative college town of San Marcos, Texas (where President Lyndon Johnson himself went to school) was thrust into antiwar movement, when a group of Texas State University students staged a peaceful antiwar demonstration, with fewer than 50 protesters sitting silently.

In the judgment of the university administration, this assembly is a violation of established university policies as set forth in the student handbook. I hereby direct you to leave this area within three minutes. Any student remaining beyond that time will be suspended from school until the fall of 1970.

Floyd Martine, Dean of Students

Most dispersed, but the remaining students would later come to be known as the San Marcos 10, and would be suspended from Texas State then and there.

The crowd was screaming at us…‘Love it or Leave it!’ ‘Let’s string ’em up!’ All kinds of ugly things…

Sallie Ann Satagaj, Student

Even though the protesters had wide-spread support, appeals to the Student-Faculty Review Board, on the argument that their constitutional rights had been violated, were denied. Later, the ACLU filed a civil lawsuit against the school administration in the U.S. Western District Court in Austin, where they argued that the administration had crafted “policy which [violated] the rights of freedom of speech and assembly granted under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.” U.S. District Court denied the group’s appeal for reinstatement, as did the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and in May 1972, the San Marcos 10 suspension appeal was submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court, but it let the lower court’s ruling stand, and the San Marcos 10 lost all of that year’s school credit.

The university administrators felt the protests were very embarrassing. They wanted to make sure it never happened again. They still felt they could rule with an iron hand, and they did not like being second-guessed. They wanted to punish the participants, so they did.

Joe Saranello, Student

The nationwide Vietnam moratoriums on college campuses throughout 1969 had succeeded in refracting the public’s opinion of President Nixon and of the Vietnam War. The San Marcos 10 and members of their generation helped end an unpopular war, and teach later generations that peaceful protest can amplify noisy ideas.