During his presidency, from 1921 to 1923, Warren Harding was generally well-liked by Americans. After his death, charges of cronyism and corruption sent him to the bottom of the list of our nation’s favorite presidents.

But one thing about President Harding was always clear, even if most of his supporters and detractors have forgotten it: Harding was one of the best newspaper editors of his time and perhaps of all time. He was, like so many other small-town legends, a true community journalist.

Buying the Star

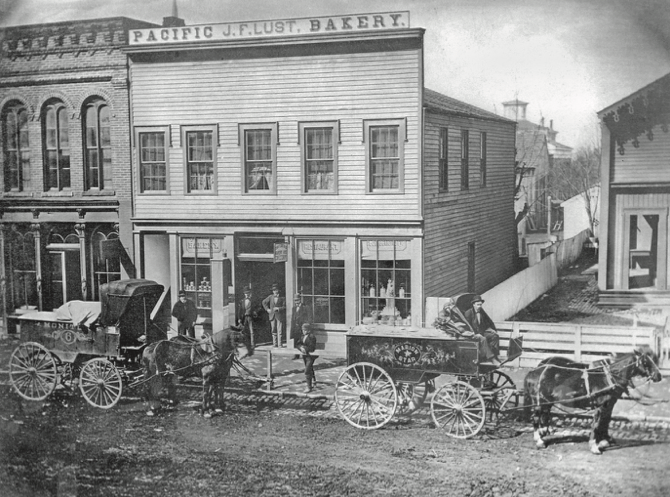

In the summer of 1884, Warren was an 18-year-old living in small-town Ohio. But he also dreamed of being a journalist. When he heard that the hometown Marion Daily Star was up for sheriff ’s sale—the paper’s record of failure was well known in the community—Warren badgered his father to buy a half interest. George Tryon Harding needed little convincing to return a vacant lot to the bank for payment and assume half of the Star’s debts, which were then placed in Warren’s name.

The newspaper would become Warren’s constant companion for all of his adult years—almost a living, breathing being in his eyes, the anchor that kept him grounded through his political career, including during his presidency.

Harding as a Writer

A newspaper could not survive in those days without publishing opinions, and Warren wrote about everything from presidential races to state issues to local arguments. His writings revealed a man who looked forward to the future of his city and his nation and showed deep, heart-felt interest in the daily struggles of his fellow townsmen.

The popular young editor was a joiner. He was a member of nearly every fraternal organization in town, minus the Freemasons. Sometimes, his enthusiasm for the weekly meetings affected his job performance the next day:

“If our dear readers notice any decrease in the amount of local news in today’s issue, as may be the case, we may satisfactorily explain the matter right here and state that the Star’s proficient news gatherer was induced to take the initiatory degree of the Merry Haymakers last evening. He was not wholly incapacitated from duty this morning, but the elacticity [sic] which characterizes his physical make-up was somewhat taken out of its agile form, which discouraged him from his customary effort to circulate his anatomy among you. We trust he will soon be able to seek his daily news budget.”

Warren was invited to card parties, weddings, dances, and sleighing groups—anything involving young people in the town. The events always received a detailed accounting in the next day’s paper, listing the attendees and decorations and applauding the sumptuous bounty of food. Thirty-some years later, President Harding told of one wedding that earned just a paragraph and still evoked shame on his part. Warren, for the first time, was not on the guestlist for a prominent local wedding. He soothed his hurt feelings by giving the event just a few sentences—the bare bones. The wedding note was so unlike his usual generous accounts that the community noticed. Warren was embarrassed that his feelings had gotten in the way of his newspaper. He swore that such an incident would never happen again.

Harding as a Boss

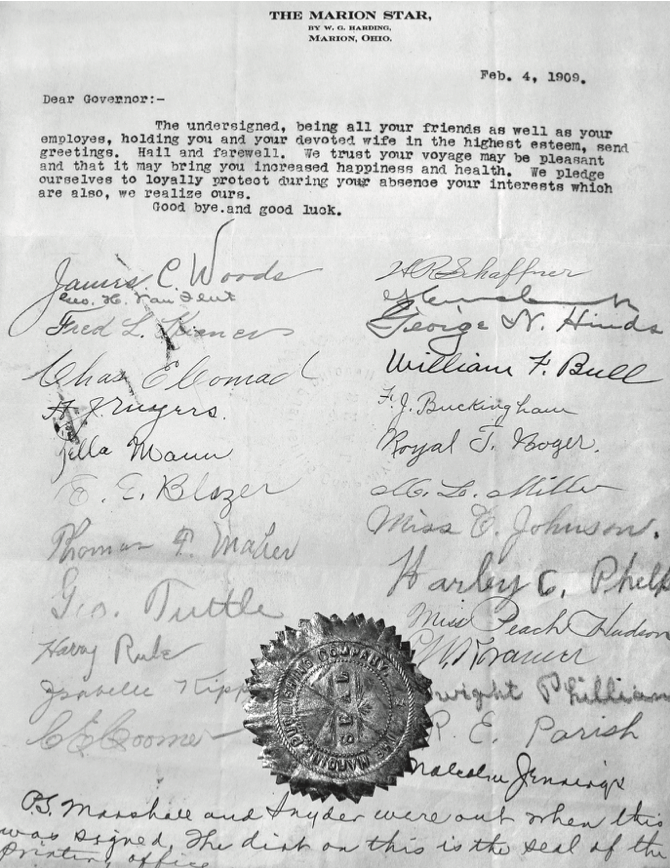

Star employees called Warren “W.G,” and he made a point of telling them that they worked “with” him, not “for” him.

Warren underscored this team philosophy with action. In the early 1900s, he offered his employees a chance to buy stock in one-fourth of the company. This unheard-of move spoke volumes to his employees about his high regard for them and gave them a personal, vested interest in the success of the Star. The Star staff was his extended family. He loaned money here and there to staffers who needed it, even to those moving on to other jobs. He did not put these loans into legal documents; he trusted that his co-workers would repay him.

Even when the boss was not in town, he made sure that the Star employees received Christmas greetings. Ad manager A.J. Myers was especially impressed with his gift of Havana cigars, and Warren reciprocated with thanks for his gift of Camel cigarettes. He also made sure that his oldest employee, Lew Miller, received his annual Christmas tribute. In a letter to treasurer Henry Schaffner, Warren wrote, “Don’t forget that it is an established custom of the Star office to give to Louis [sic] Miller a five dollar gold piece on ’Xmas Eve, or the equivalent thereof. I would not want to forget this custom, because Miller is growing old and, in all probability, will not be working for us many years longer.”

Warren cared deeply about the well-being of his employees. Birdie Hudson, who had been employed as a combination stenographer-bookkeeper-secretary at the Star since about 1907, required surgery and was a patient at Grant Hospital in Columbus. She was under the care of Warren’s brother, Dr. George Tryon Harding Jr., who was nicknamed “Deacon” by close friends and family. Harding wrote light letters to Birdie, encouraging her in her recovery: “[Deacon] tells me you are pale and thin and nervous but this is no news to me for you were always that. You would stand no more show of winning a prize in a fat woman show than Henry Schaffner would win a prize in a contest for the best head of hair.”